Larrilou Carumba, a mother of three and a member of Unite HERE Local 2. Photo courtesy of The San Francisco Labor Council

Larrilou Carumba is a mother of three who works as a housekeeper for several hotels. A longtime San Francisco resident, she and her children were forced to leave the city when her landlord doubled the rent. The four now share a single room at her sister’s home in San Leandro, 30 miles away from her workplace. Carumba lives in the gray zone that many working people fall into—unable to afford a home at market prices, but earning too much to qualify for government assistance such as Section 8 rental subsidies or traditional tax-credit low-income housing. Carumba is a member of labor union Unite HERE Local 2 and earns over $26 an hour, but still can’t afford to live in San Francisco. “I’m lucky I have that kind of salary,” she said. “But I’m not lucky enough to have a house.”

The rampant gentrification of working-class neighborhoods in “hot market” cities like San Francisco has pushed many working families like the Carumbas out of the cities where they work and into long commutes. More and more people are shut out from housing they can afford, while investors continue to profit regardless of the impact that their business practices have on a city’s ability to maintain a viable and diverse economy. In conversations with several Bay Area labor unions (NUHW, SEIU 2015, SEIU 1021, Unite HERE Local 2, etc.), we found that after low wages and inadequate or nonexistent health benefits, housing insecurity is the next biggest issue affecting workers.

“Housing Our Workers: Getting to a Jobs-Housing Fit” is a new report resulting from a collaboration between the Council of Community Housing Organizations, the San Francisco Labor Council, and Jobs for Justice. The report found that only 7 percent of workers can afford to rent market-rate housing in San Francisco without spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing. In many occupations, virtually no workers can afford housing in San Francisco or even in nearby inner-ring cities. And while housing for all income levels fell short, only 5 percent of moderate-income San Francisco households’ needs were met by available housing. Housing policy needs to evolve to encompass strategies for meeting these tremendous low-income and moderate-income needs so that no one is left behind.

Access to dignified and affordable housing has always been a challenge for low-wage workers, but the combined effects of a predominantly white middle-class “return to the city” starting in the early 2000s, the 2008 financial crisis, and the tremendous growth of high-tech has made it extremely difficult for middle-income households to find housing as well. Meanwhile, “smart growth” planning assumes a predominant focus on white-collar jobs, despite the renewed attention in the political discourse since COVID-19 on everyday “essential workers.”

Unless cities build housing systems that expressly support and provide decent, stable, and safe affordable housing for the working people and families who are the lifeblood of those cities, we face a future of increasing racial and economic segregation, with low- and moderate-wage workers pushed out to the periphery or forced into untenable rent burdens and overcrowding.

The starting point has to directly involve organized labor and the housing justice community and must build practical and political relationships between them.

Housing: A Long-Time Labor Struggle

Organized labor has been involved in housing issues for decades, from the New York housing cooperatives of the 1930s and the St. Francis Square Co-op funded by the ILWU in San Francisco in the 1950s, to the AFL-CIO’s Housing Investment Trust today. But labor voices are rarely at the table in shaping, advocating for, and negotiating housing “solutions.” Meanwhile, terms like “workforce housing” and “middle-income housing” have become weaponized as a wedge issue against low-income housing or anti-displacement policies, as market-rate developers and savvy politicians seek to capitalize on the growing housing crisis faced by middle-income worker households. It’s easy to talk about workers in the political discourse; it’s another thing altogether to talk with workers about their housing needs, and even more “radical” to collaborate with workers to suggest and advocate for tangible policy solutions.

Since its inception 40 years ago as San Francisco’s coalition of affordable housing developers, the philosophy of the Council of Community Housing Organizations (CCHO) has been to see itself as part of a broader progressive movement, building political power in alliances with tenant advocates, health and human services organizations, faith-based groups, and labor.

CCHO’s work with the San Francisco Labor Council and Jobs with Justice is the result of the intentional cultivation of relationships over the last several years in this political context: housing advocates throwing down on campaigns for labor issues and vice versa, labor putting its muscle into support for campaigns on affordable housing and housing justice issues.

In many respects, a successful 2016 campaign that pulled together labor and housing advocates to beat back an assault by the real estate industry on affordable housing policy (propositions P and U, “peeyew”!) sparked the unity of common cause. Earlier that year, housing advocates had worked hard to successfully increase the inclusionary housing obligation, including a new middle-wage worker tier. In November of 2016, however, real estate interests responded by introducing propositions P and U, which would roll back those housing victories.

To understand those ballot measures, some background is required. The San Francisco Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development administers most programs to build or rehabilitate affordable housing. The effect of Proposition P would have been to require the city to bring in out-of-town and for-profit developers to build affordable housing on city-owned property. Both affordable housing advocates and labor quickly opposed this, arguing that it was an attack on community-based development and the union-built housing that community developers in San Francisco produce.

Proposition U would have changed the affordability for on-site inclusionary below-market rate rental units from 55 percent of AMI to 110 percent of AMI, eliminating housing for lower-wage San Francisco workers, and of course reducing the cost for developers to meet the city’s mandated inclusionary housing requirements. Labor understood that a united-front strategy meant expanding the benefits of affordability without reducing benefits for lower-wage workers.

Much of the messaging put forward by real estate interests used the wedge language mentioned above. Advertisement campaigns espoused the benefits the proposed law would bring for middle-income workers, but labor leaders saw through these attempts at division among workers along class lines and recognized the harm that these policies would enact on the housing stability of the overall worker force.

[RELATED ARTICLE: Building Bridges, Building Muscle, Building Momentum]

A united advocacy with affordable housing groups successfully defeated the bill and provided a strong footing to build the relationship between affordable housing groups and organized labor, and co-create a policy framework that can better address the range of housing choices that workers and their families truly aspire to. This had never been done before. Mutual education took place through Jobs with Justice’s housing committee, and through United for Housing Justice, a coalition that developed out of the No on P and U campaign. A key focus of this alliance is remembering the broad spectrum of incomes that make up workers left behind by the real estate industry. As John Doherty of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 6 said, “It used to be that a blue-collar worker in San Francisco was pretty much guaranteed a middle-class life. With the seemingly ever-escalating cost of housing, that’s no longer the case, and that’s not right. Too many of our members, and indeed all working-class people, are struggling to make rent and face brutal commutes, same as our brothers and sisters in lower-wage sectors. We need to provide affordable housing that matches all worker needs, and solidarity means that won’t come at the expense of low-income workers.”

Effective alliances that are durable over time and build lasting, leverageable power are based on a foundation of trust that differs from temporary and transactional relationships that form around specific one-off campaigns. The work to build such a durable alliance can be long, slow, and sometimes messy. The success of the alliance in San Francisco did not happen quickly. The city has a long history as a union town that has uniquely shaped the political landscape and the coalitions that form to advocate for power and policies.

[RELATED ARTICLE: Sprawl vs. Unions]

A unified housing-labor-community alliance pushing for better and more creative affordable housing policy is a force that threatens the status quo interests that hold power, in this case the entrenched system of real estate speculation. Therefore, the alliance is constantly challenged and provoked by attempts to divide the allies, a tactic that the labor community is quite familiar with over its history of struggle.

But the push to divide and conquer cuts both ways and it is often said in labor organizing that the best catalyst for organizing is a bad employer. The experience of a galvanizing united campaign to stop the real estate industry-led propositions P and U is a case in point, and labor has been attuned to similar ploys to play class politics, both within labor and between labor and housing justice allies, since then. There is more than enough common cause to tie housing advocates and labor together in the struggle for housing justice.

Creating a Joint Framework

“Housing Our Workers,” the recent report that resulted from a collaboration between housing advocates and organized labor, is the culmination of a two-year joint project between the two groups and a benchmark for a San Francisco labor/housing/community coalition in the future. This effort has planted the seeds for a lasting alliance.

The report uses what it calls a Jobs-Housing Fit analysis to compare worker incomes with the affordability of available housing. It examines the incomes of worker households and assesses if they can afford to pay for adequate housing in San Francisco. The extent to which they can or cannot afford housing measures the adequacy of the city’s Jobs-Housing Fit and how much we need to correct that “fit” through city policy. The findings demonstrate severe discrepancy between the wages of San Francisco’s essential worker households and actual housing prices. Data collected from thousands of unionized workers in San Francisco found that workers across the income spectrum are increasingly struggling to find affordable housing within San Francisco. The critical frame for affordable housing advocates is that this expansion of the housing work to middle-wage workers can’t come at the expense of affordable homes for low-wage workers and fixed-income folks.

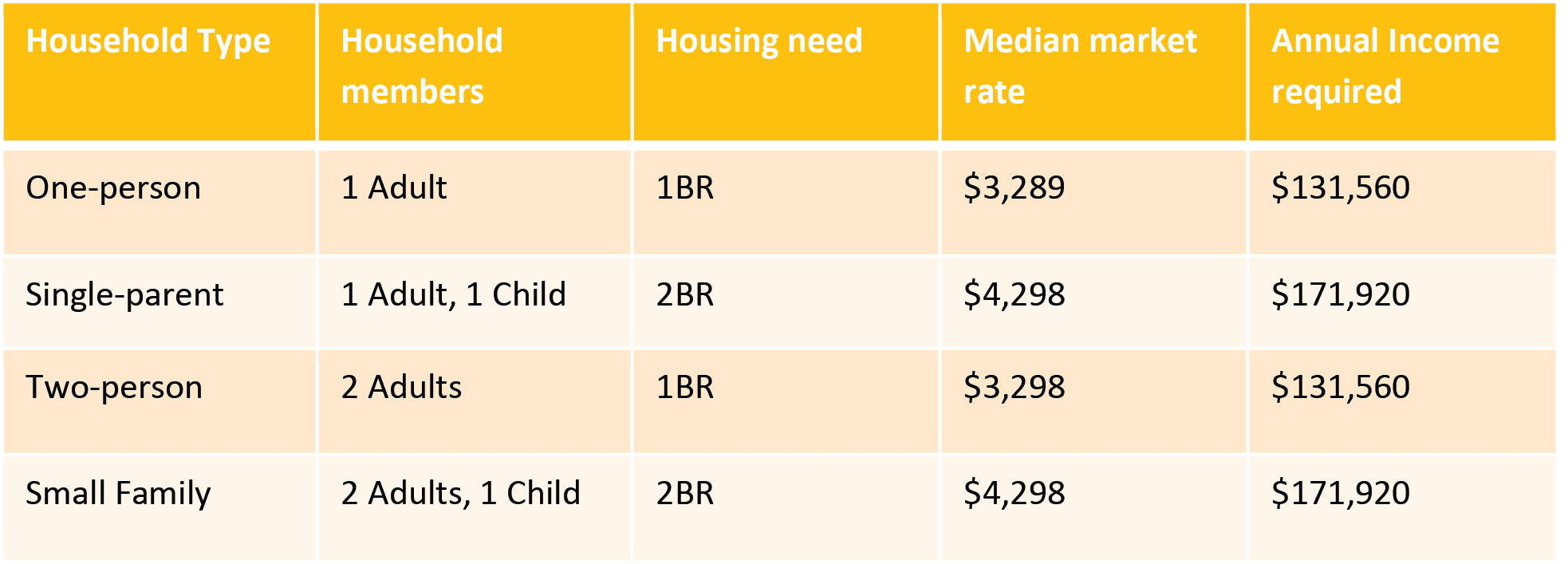

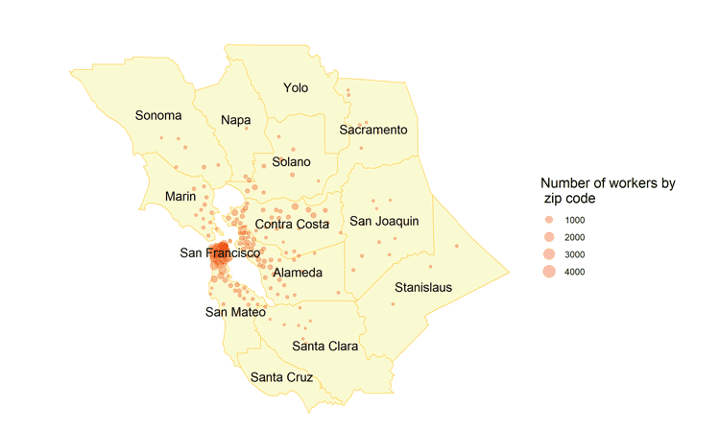

Annual Income Required to Afford Median Market-Rate Rent Based on Household Size. Data compiled by UC Berkeley Labor Center

The conversations and collaboration with labor leaders and everyday rank-and-file workers revealed greater nuance that is critical to shaping a “housing solutions” framework truly designed for workers and their families. Housing issues are not solely about affordability, and through these conversations, we learned that many union workers were also concerned about home sizes to accommodate different family configurations, proximity to open space, access to childcare and other critical services, and ability to build equity for housing “mobility.” The worker stories point to the need to directly address family-housing needs by expanding housing and childcare requirements in zoning and planning regulations. Lack of housing affordability also impacts quality of life by forcing workers into super-commutes as they move farther away from jobs in city centers in search of affordable housing. As John Doherty of IBEW Local 6 told us, even with electrician wages, he could not afford to stay in the city he grew up in. Now he is “locked behind a steering wheel for a couple hours a day, like many of our members.”

The unique perspective that labor voices bring to conversations about housing needs and aspirations is a result of the long and patient collaboration between our organizations. Trust and durable alliances bear real fruit.

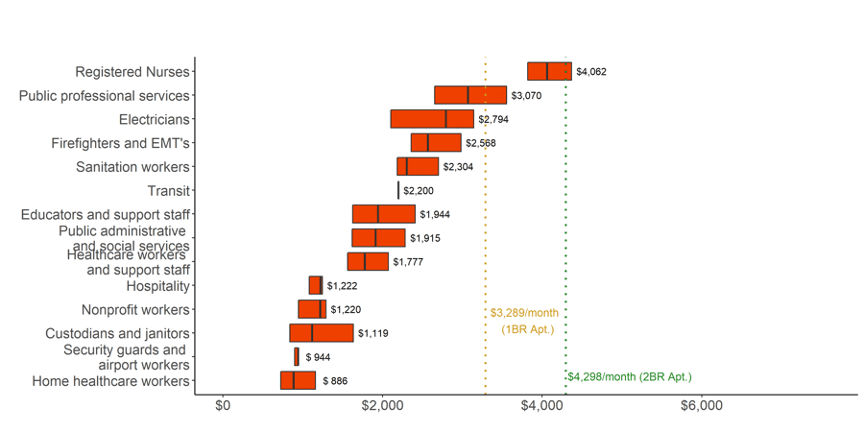

Median rent affordable to San Francisco workers by occupation compared to median market rent. Affordability is defined as 30% of income. Data compiled by UC Berkeley Labor Center

The housing affordability crisis is the outcome of real estate speculation facilitated by public policy choices that incentivize this behavior. Housing stability and long-term security for workers, in proximity to their workplaces, depends on solutions that de-emphasize land and housing as commodities, that support housing production that is needs-based rather than simply market-based, and that reduce incentives for speculation—with a goal of achieving a true Jobs-Housing Fit.

The Housing Our Workers report provides a framework of “3 Ps”: it aims to PROTECT residents and communities, PRESERVE existing housing within communities, and PRODUCE new housing that meets the affordability needs of these vulnerable workers and their families. Equitable land-use policies that harness public benefits and ensure good jobs are key to controlling land costs and prioritizing affordable housing that meets worker needs. As in other national labor conversations, whether about a Green New Deal or Medicare for All, big solutions that match the scale of the problem are necessary. This means fighting for sufficient land and funding to meet actual needs across the income spectrum of workers, including creative strategies for new revenue and land banking programs.

This joint framework has shaped our current campaign work: the dedication of surplus school district sites for educator housing (and a fight-back against privatizing those sites); a transfer tax dedication of $64 million to housing preservation; and advocating for the city’s Housing Stability Fund to renew investments in limited equity cooperative ownership and land banking for social housing. Labor in San Francisco will be front and center in the emerging strategies around mixed-income social housing development.

The labor community is getting increasingly organized around housing issues—in hearings, press conferences, at the policy negotiating table, and as leaders in campaigns for housing measures. It is not just a matter of who builds housing, it’s now centrally about who can live in the housing that is built in our communities and who can stay in our working-class communities as gentrification and displacement pressures squeeze more and more families out.

The Housing Our Workers project demonstrates that an alliance of housing and labor leaders can turn aspiration into action. It calls on labor and housing justice advocates to harness our collective organizing power and press policymakers and technocrats to put these solutions in motion.

There’s a promise in the common struggle for housing to build working-class solidarity in a way that spans the individual unions’ struggles for material gains for their own members. Poor conditions can lead to the kind of unity needed to create change. The shared experience of an unjust housing market in relation to real estate and development can yield deeper working-class consciousness and greater power.

Find the full report here: “Housing our Workers: Getting to a Jobs-Housing Fit,” by SF Labor Council, CCHO, JwJ, with UC Berkeley Labor Center

Comments