This article is part of the Under the Lens series

The Racial Wealth Gap—Moving to Systemic Solutions

iStock photo by olaser

George Floyd’s horrific public murder in May 2020 ignited yet another round of protests demanding an end to police violence. This time, corporate America decided it needed to respond, and many executives and boards of directors vowed publicly to finally do their part to address systemic racism. By October 2020, a slew of Fortune 1000 companies had earmarked a total of $66 billion to support racial equity.

Of the corporations opening their coffers, financial institutions made some of the heftiest post-protest pledges. But banks also have a historically conflicted relationship with pursuing racial equity and closing the racial wealth gap. Most played a direct role in underwriting racism, and ongoing evidence of bias in lending exists to this day. In 2021, discrimination toward non-white credit applicants remained in everything from COVID-related Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) funding to applications for auto loans.

On the other hand, after decades of complying with the Community Reinvestment Act (the CRA exists specifically to check banks’ discriminatory behavior), the same major financial institutions have substantial and sophisticated community development departments that manage direct financial support for mission-driven community development financial institutions (CDFIs), affordable housing developments, lending practices, and mortgages in neighborhoods their corporate entities commonly ignored or outright refused to serve in the not-so-distant past.

Unlike the new kids on the racial equity funding block, many legacy financial institutions (and their related foundations) had been talking about and trying to address the racial wealth gap long before 2020. Nonetheless, given that the gap is as wide today as it was the year MLK was assassinated and the two-tiered financial system is still solidly in effect, it makes reparative sense that banks step up their equity game. And, indeed, the dollar amounts promised in the months following Floyd’s murder were unprecedented in terms of sheer numbers. At latest count, U.S. corporations had pledged $200 billion to a slew of initiatives attempting to fight systemic racism—with banks backing almost 90 percent of it.

Cash Commitments with Context

Several of America’s largest banks and financial institutions were quick to announce investments directly related to Floyd’s death. In June 2020 alone, Bank of America (the nation’s second largest bank) and PNC (seventh largest) each committed $1 billion, and U.S. Bank (fifth largest) pledged $116 million. In September 2020, Citi (fourth largest) announced its $1 billion “Action for Racial Equity” initiative, and Truist (sixth largest) made a $40 million initial donation to establish a nonprofit to support CDFIs in funding “racially and ethnically diverse small-business owners, women, and individuals in low- and moderate-income communities.”

Wells Fargo (third largest) in July 2020 donated $400 million of its PPP processing fees to its Open for Business Fund, earmarked “for Black and African American entrepreneurs and other minority-owned businesses.” In May 2021, Wells Fargo gave a $20 million boost to an existing $50 million evergreen investment fund for the Black Economic Alliance Foundation.

“Wells Fargo is very involved in the homeownership piece and is really trying to bring banks and the [Office of the Comptroller of the Currency] and other organizations in,” says Eileen Fitzgerald, Wells Fargo’s head of housing affordability philanthropy. “They’re trying to look at some of these systemic issues that no one entity could solve, and it’s very focused on racial equity.”

The nation’s biggest and most valuable bank, JPMorgan Chase, issued a statement in June 2020 supporting the protests over Floyd’s murder and closed early to observe Juneteenth. A few months later, in October, the company, whose assets total $3.19 trillion, announced it planned to invest $30 billion over five years to increase Black and Brown entrepreneurship and homeownership. At the time, company CEO Jamie Dimon called racism a “tragic part of America’s history” in a prepared statement that also stated, “We can do more and do better to break down systems that have propagated racism and widespread economic inequality.” Dimon, a white man, made nearly $32 million in 2020 from his job at JPMorgan Chase.

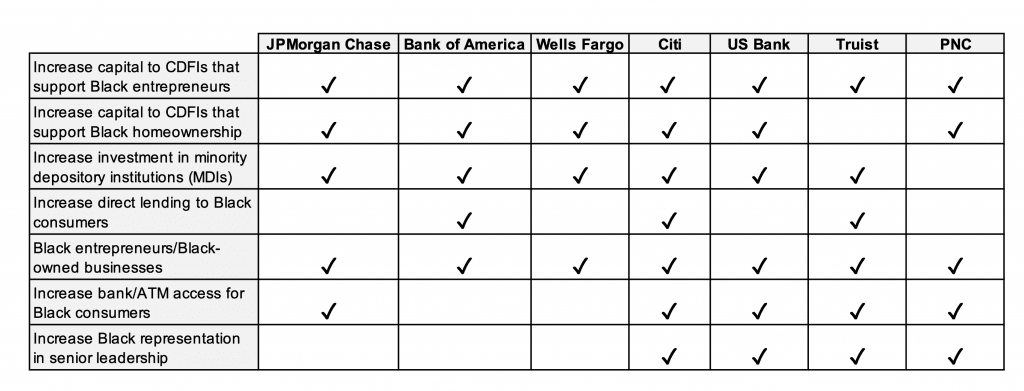

What exactly are the banks doing to advance racial equity? The financial institutions Shelterforce reviewed each created unique initiatives with their own budgets, time frames, and terminology. Click on the chart above for a more detailed breakdown.

Sounds Big, But How Big Is It?

Doing better doesn’t necessarily mean doing enough. Consider JPMorgan Chase’s $30 billion pledge: When spread over its five-year life span, that’s just $6 billion a year to a company worth more than $3 trillion—or 0.2 percent of its total value. Put another way, in 2012, The New York Times reported a then-newsworthy trading loss by the company as “the $6 billion blunder [that] has turned out to be no more than a minor ding on JPMorgan Chase’s mighty balance sheet.”

JPMorgan Chase’s balance sheet is indeed mighty, but its value is less than one-quarter of America’s estimated racial wealth gap: A pre-pandemic analysis put Black American households as much as $11.2 trillion behind white households. To put that in perspective, Black households’ median wealth in 2019 was $24,100, compared to $188,200 for white households.

Keep in mind also that most of these financial commitments are not grants or donations; they’re business opportunities. An August 2021 analysis of all corporate commitments found nearly all of the $45.2 billion JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America pledged between them to increase racial equity is earmarked for profit-making investments and loans—more than 50 percent of it for funding mortgages. JPMorgan Chase, for example, pledged $8 billion to originate 40,000 home purchase loans for Black and Brown families.

If all goes as projected—and banks rarely commit large sums of money to investments that don’t offer a solid probability of a positive return—both institutions should get these whole investments back, plus interest. So while the dollar amounts going to Black and Brown communities are significant, so is the potential for these banks to earn income from their initiatives in the form of interest payments, finance charges, and all the other fees that come with funding and servicing mortgage loans, says Robert Villarreal, chief external affairs officer at CDC Small Business Finance, a California-based, mission-driven small-business lender.

“A lot of folks who aren’t in the field hear $30 billion and think, ‘Oh, they’re giving away $30 billion.’ No, they’re not. A really tiny amount is given away, and the rest is [going to] lending,” he says. “Sometime in the first or second quarter of 2022 they should be submitting reports . . . The question is what was your return on that investment?”

We reached out to the nation’s seven largest financial institutions; the ones who got back to us with more than boilerplate answers all said they are on track to deploy the funds as promised, but that it is too soon to be able to assess any results. None provided any answer to questions about whether the loans and investments associated with their racial equity initiatives will be made with different underwriting or terms than their traditional loans.

While the money big banks promised is flowing and the total dollar amounts are massive, the five-year, multi-initiative, loan-focused distribution process means that “what looks like a waterfall going into the funnel ends up being a drip out the other end,” according to Tynesia Boyea-Robinson, CEO of CapEQ, an impact investing advisory firm, and former chief impact officer at Living Cities, a collaborative of large foundations and financial institutions focused on increasing racial equity in financial systems.

What these initiatives look like in practice is that the billions of dollars are carved into chunks of millions to be distributed to various CDFIs, community development corporations, nonprofits, and other organizations. Those millions are whittled even smaller by intermediaries slicing bits away via fees and other third-party payments, until what’s left is “nothing that could sustainably address the problem,” Boyea-Robinson says.

Audits

One way to determine whether financial institutions are making meaningful internal changes is with a racial equity audit—preferably one conducted by an outside third party. Racial equity audits are one facet of the increased scrutiny many public companies are placing on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations following investors’ requests to see large corporations address social justice concerns.

Racial equity audits can take many forms, but usually include allowing an independent, objective third party to holistically analyze a company’s policies, procedures, products, and practices to identify internal inequalities and ways in which operations might be contributing to systemic racism. In the last few years, large companies like Starbucks and Tyson Foods have allowed such audits, and just last month New York State Comptroller Thomas P. DiNapoli filed shareholder proposals calling for Amazon, Dollar Tree, and Chipotle Mexican Grill to follow suit.

Early in 2021, a coalition of stakeholders, including labor unions, filed shareholder proposals asking several Wall Street banks to participate in a racial equity audit. Only Morgan Stanley, which is currently facing a gender discrimination lawsuit filed by its former head of diversity, agreed at first to participate in an external audit. The others initially urged a “no” vote, arguing they were making enormous strides in equality and didn’t need auditing. Citi changed its position in October 2021, and CEO Jane Fraser in a November blog post explained that the company “recognize[d] the need to hold ourselves accountable, starting with being transparent about where we are and where we need to continue pushing to improve.”

Changing the Two-Tiered Financial System

When banks invest in low-income communities, they often allocate funds “in a special bucket in case everything goes wrong” rather than considering their investment part of regular business, says Dana Lieberman, senior vice president for capital solutions at IFF, a mission-driven lender serving the Midwest. Lieberman suggests that big banks’ next step to really advancing racial equity would be to work toward fundamentally changing the way they do business with Black and Brown communities rather than funding temporary initiatives.

Terry Young, IFF’s senior vice president and chief credit officer, agrees. He says banks need to ask themselves whether the months after Floyd’s death were “a moment, or was it a movement? The difference between a moment and a movement is the level of sacrifice; a movement requires sacrifice.”

Some practical and specific sacrifices legacy banks could make were spelled out in a June 2020 New York Times op-ed. In it, Angela Glover Blackwell, PolicyLink founder in residence, and Michael McAfee, PolicyLink’s CEO, outlined four distinct policies the financial industry should adopt for Black customers in order to meaningfully compensate for past wrongs and really start to close the nation’s racial wealth gap. The policies include canceling consumer debt, eliminating banking fees, providing no-interest business loans, and offering interest-free mortgages. While this op-ed specifically addresses Black customers, similar measures are likely warranted for other historically marginalized groups as well.

Unsurprisingly, the systemic reforms the seven banks discussed in this article—whose combined assets equal more than $10 trillion—have committed to implementing are significantly more modest than the radical policy changes Blackwell and McAfee proposed.

Banks are structured to make as much money as possible from their investments. Therefore they don’t often invest when they suspect the profit won’t be large enough, or when they’ve got to invest big money up front in order to figure out that market segment. The CRA was supposed to solve this problem by requiring banks to invest in marginalized or low-income communities in their service areas.

But CapEQ’s Boyea-Robinson points out that rather than change their underlying business models, banks often meet CRA requirements by delegating their investments to CDFIs—which, in turn, do the actual lending legwork in low-income communities, allowing banks to claim CRA credits and keep government regulators happy.

What this means, though, is that the banks still aren’t lending money directly to poor folks, or to Brown and Black folks, at proportionate levels. Instead, they lend money to CDFIs, which in turn fund and service loans to low-income, often Black or Brown borrowers.

But CDFIs can’t be everywhere, and they don’t have the brand recognition the big banks bring. So while CDFIs do a good job with the money they get, legacy financial institutions denying Black and Brown borrowers access to mainstream sources of capital leaves vast swaths of creditworthy personal and business loan borrowers at the mercy of extractive financing options—such as payday lenders, high-fee checking accounts and ATMs, and even higher interest rates when refinancing existing mortgages.

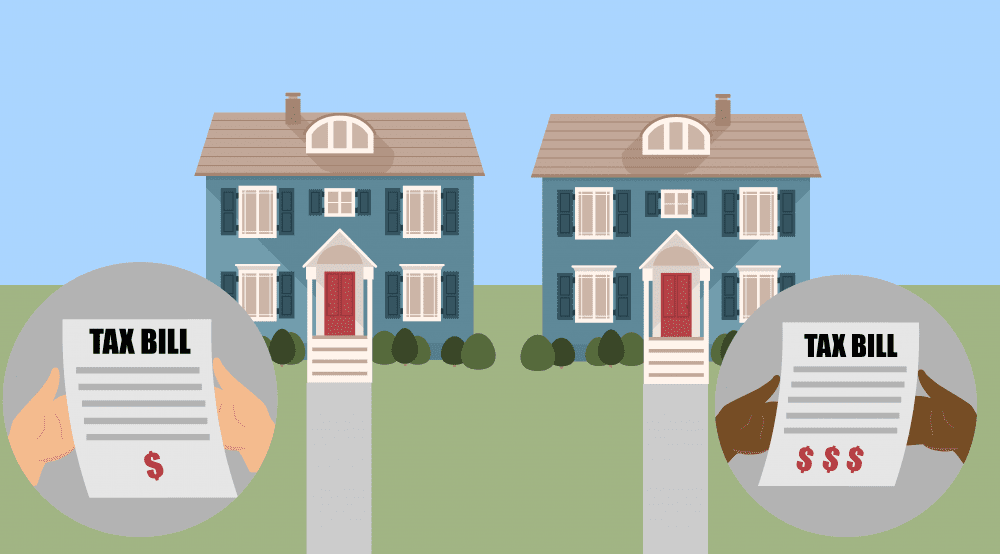

Black borrowers are still 80 percent more likely than white borrowers to have their home mortgage applications rejected, and even highly qualified Black clients face disparate treatment by big banks. When Black borrowers do get a mortgage loan approved, they’re often saddled with higher interest rates than white borrowers who earn similar incomes. Black business borrowers also regularly face discrimination: Black entrepreneurs are denied business loans twice as often as their white counterparts. In 2018, 49 percent of white business owners’ loan applications were approved compared to just 31 percent of Black business owners’ applications.

“The George Floyd incident is pushing everyone [to ask], ‘What part did my institution or my institution’s history play into and contribute to this?’” Boyea-Robinson says. “So shifting power, redefining risk, and promoting racial justice are what every investing institution has to do and has to embed in their work if they claim a commitment to racial equity with their capital.”

For banks to shift their lending standards to make loans accessible to Black and Brown borrowers, they need to interrogate internal standards and policies surrounding actual versus perceived risk, says Boyea-Robinson. Racist and biased underwriting standards are so ingrained in banks’ lending policies through reliance on things like credit scores and other “standardized” risk markers, that without pointed interrogation they will continue to exclude creditworthy borrowers of color.

“Risk perception is the place people have the opportunity to say, ‘I’m not being racist. I put your name in and this score came back,’” Boyea-Robinson says. “It’s really about examining what are the biases baked into the system that help perpetuate inequity. A great example is still requiring collateral from people in Native communities whose land was stolen. How are they going to have a high credit score?”

The hope is, with the influx of mission-based capital earmarked for non-typical borrowers, that banks will use this moment to figure out how to fairly extend credit with fewer disparate outcomes.

Several of the nation’s legacy banks have expressed general intentions to change their business models for the long term to reduce the racial wealth gap, but few offered specifics. JPMorgan Chase in an October 2021 update noted its plans to “further expand credit through targeted adjustments to how it evaluates credit applications.” Whether the biggest financial institutions have the wherewithal or the impetus to examine and redress their standards around borrowers’ actual risk versus their perceived risk remains to be seen.

“The model should be how can we build a sustainable lending platform that works for the long term and not just have it be an initiative we did in the spring of 2021,” Lieberman says. “In a year from now will this be a normal way of doing business, or will it be that the money ran out so now it’s over?”

Editor’s Note: Wells Fargo, Chase, and PNC provide financial support for our work.

|

Help keep us strong by becoming a Shelterforce supporter. |

Comments