Broad Street in Newark, New Jersey. Photo by flickr user Axel Drainville, CC BY-NC 2.0

Did the Greyston Bakery continue its open hiring policy? What happened to squatters living in abandoned buildings in New York in the ‘90s? We also take a look at the outcome of grantees who got control of a foundation, whether San Francisco activists were able to build supportive housing for the homeless after they won the first battle for land, and if Newark, New Jersey, was able to avoid gentrification.

Open Hiring, Vindicated

“Community Baking at the Greyston Foundation,” 1995

In 1995, we ran a story about the amazing Greyston Bakery in Yorkers, New York, which was founded in 1982, but was expanded notably in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. The bakery’s owners wanted to use the for-profit enterprise to strengthen the community, and they offered jobs to anybody who needed one—a concept called open hiring where there are no background checks, no drug testing, and no experience necessary.

Greyston Bakery, 2008. Photo by flickr user Stephanie Young Merzel, CC-BY-2.0

Well, we have good news: The bakery is still going strong, making 8 million pounds of brownies and blondies a year, selling to companies including Ben & Jerry’s and Whole Foods. And it has continued its hiring practices. The bakery has also become a certified B Corp, highlighting the company’s mission to use its business as a force for good.

Shelterforce has written about the Ban the Box movement and last year published a whole issue around the criminal justice system, so we’re delighted that Greyston is still out there proving that bias in hiring isn’t necessary for a successful business.

—Lillian M. Ortiz

End of a Squatting Era?

“Battle Over 13th Street,” 1995

In 1995 a group of squatters living in and caring for a set of abandoned city-owned buildings on a block of East 13th Street in New York City’s Lower East Side faced displacement—to make way for the development of formally designated affordable housing, including units for those leaving homelessness. Rents had started to rise in the mid-’90s after the late 1980s real estate recession, but the Lower East Side was still a quirky neighborhood of artists, not full of “condos, hotels, and pricey restaurants,” as the Gothamist describes the area today.

The squatters resisted, claiming they’d been in the buildings long enough to claim ownership by adverse possession (10 years or more) and were partially responsible for the improvements that made the buildings desirable for development. Unlike recent housing takeovers, they had been living in the buildings under the radar and didn’t have political demands beyond staying in their homes. The city argued the buildings were in dangerous disrepair, and the squatters, many of whom were artists, were not necessarily low-income. The standoff, which attracted the support of many neighbors, ended with tanks, handcuffs, and media blocked from entering.

What happened? Though the clash we wrote about was not the last hurrah, with squatters continuing to fight in court and sometimes reclaiming the buildings for periods of time, they were eventually evicted in 1996. The Lower East Side Coalition Housing Development, the nonprofit developer the city was working with at the time did purchase and develop these units as affordable housing after the squatters left and they still manage them. The buildings are called Dora Collazo, and include 85 units.

Meanwhile, in an apparent about face, in 2002, the city turned over 11 buildings in a nearby neighborhood to long-time squatters.

(Incidentally, “Battle Over 13th Street” is the first article Shelterforce editor Miriam Axel-Lute, then a college intern, ever wrote.)

—Miriam Axel-Lute

Democratic Philanthropy—Successful, But Still Rare

“Grantmaking Power to the People,” 1999

In 1994, a Southern philanthropist did something unprecedented—she turned control of her foundation over to the grantees. The grantees, largely rural grassroots organizing groups led by people of color in the South, created a democratic structure for the newly named Southern Partners Fund, which was launched in 1999 with a formal membership and elected board.

The experiment succeeded—over 20 years later, Southern Partners Fund is thriving, with its mission strong, membership and democratic structure intact, and one of its original board members as executive director.

It has not, however, to our knowledge, spawned any similar forays into democratizing philanthropy, though the number of foundations that have been willing to fund grassroots organizing has been inching upwards.

—Miriam Axel-Lute

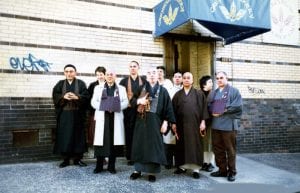

Newark on the Rise

“Tales of Three Cities,” May 2001

In May 2001, the gentrification of Hoboken, New Jersey, a small city located an easy hop across the Hudson River from Manhattan by multiple forms of transit, was complete. The once-working-class city was now a playground for childless young adults with jobs in New York City and a desire for slightly cheaper rent. Were there lessons to be taken from how it happened for other New Jersey cities? Shelterforce spoke to community developers in New Brunswick, a college town in the center of the state, and Newark, the state’s largest city.

At the time, luxury developments were starting to pop up in New Brunswick, having taken people who followed housing in the city somewhat by surprise. It was mostly not a concern throughout Newark, which was much more focused on not losing population and finding ways to combat ongoing disinvestment. Newark was, however, also an easy commute from Manhattan, and Joseph Della Fave, then director of the Ironbound Community Corporation (ICC) and formerly of Hoboken, thought it something to keep an eye on.

Newark wasn’t Hoboken, of course—Ray Ocasio director of the CDC La Casa De Don Pedro then and now, noted that the city had a strong network of community-based organizations that Hoboken hadn’t, organizations that could both sound the alarm and build in affordability if the trends ever went in that direction. In 2001, however, Ocasio was more concerned that the neighborhoods have enough amenities to attract market-rate tenants than about affordability effects of market-rate development.

In 2021, however, Newark hit a milestone few thought it would ever achieve—the top 10 cities for most expensive rent, coming in at No. 9 in February. Zumper’s February rent report showed Newark’s median rent having jumped 31.6 percent from February 2020 to February 2021. (It did, however, fall by 7.4 percent from February to March, dropping out of its No. 9 slot.) The pandemic-driven drop in rents in other expensive cities around the country seem to have combined with a slow and steady in-migration over the past 5 to 10 years to have boosted Newark into the top ranks.

This growth, however, doesn’t necessarily reflect conditions in the whole city, so much as in the downtown, near two train stations, and in the nearby Ironbound neighborhood. And that’s part of why Ocasio says he’s sticking to what he said in 2001. There’s still a long way to go, he notes, in terms of dealing with vacant property and quality of life in other parts of the city. “People are rent burdened in Newark. That has to do with their income and lack of choice,” he says. “So elevate their income and build affordable housing.”

Nonetheless, Ocasio is optimistic. He mentioned improvements to the schools, and says he sees younger African-American professionals choosing to move to Newark as a majority Black city that they expect will be hospitable, much like many flock to Atlanta.

Gerard Joab, who was working at Newark LISC at the time the original article was written and now is the director of St. Ambrose Housing Aid Center in Baltimore, says the thing that stands out when he talks to colleagues in Newark these days is “a different sense of hope, which we didn’t have back then. Back then we were just looking for any glimmer of advancement, anything that we could hold on to. And I think now the conversation is very different.” Joab credits local organizers and funders who kept going anyway, as well as state-level advocacy for affordable housing funding, with helping to create the conditions for the change.

Ocasio’s predictions did hold true on some fronts—Newark has been more proactive than Hoboken was. Led by ICC, La Casa, and many other colleagues and organizers around the city, and with the support of a progressive mayor in Ras Baraka, Newark passed an unusually strong inclusionary zoning ordinance in 2017 and have been shoring up the city’s rent regulations and organizing for a right to counsel and other anti-displacement protections.

CDCs were, however “taken out of the development game” for a long time under the administration of Gov. Chris Christie, notes Ocasio, which was disappointing, with capacity disappearing along with funding. That’s on the mend now, thanks to a new administration and a lot of state-level advocacy, but there’s a lot to recover from.

Della Fave reflects that while some ways he feels similarly to how he did in 2001, the situation is quite different. Actual imminent fears of displacement have only been on people’s minds for the past 5 to 10 years, and that has been increasing. While perhaps few have been pushed out because of costs as of yet, the dynamics still sound familiar. For example, the residents of a public housing development fought long and hard for a nearby Riverfront Park, only to turn around and face threats of displacement by demolition once the park was realized. (ICC helped the tenants organize and fend off this threat; they were instead at the table for redevelopment plans that include a right to return.) Others feel displacement coming when developers pitch downtown luxury housing for “men in suits.” It feels like “the future of the city was not for them. That they weren’t good enough to be hanging around for the revitalization, for the investments that were taking place,” says Della Fave.

Should Newark be concerned about displacement? “We should always be concerned about it,” says Joab. “I don’t think we get will ever get to the place where we say, we have addressed the need for affordable housing. There will always be people pushed out of the housing market.”

“I’m a product of having seen, you know, the violent displacement that took place in Hoboken,” says Della Fave, “and never wanting to see something like that occur again. When you see the early signs, you better respond quickly and get ahead of the curve. And that’s what we’ve been trying to do probably for the last at least five years. What we say at Ironbound Community Corporation is ‘Always uplift, never uproot.’”

—Miriam Axel-Lute

Winning Was Only Half the Battle

“San Francisco Housing Activists Win Land and Shift the Debate,” 2004

In 2004, Shelterforce wrote of the San Francisco Surplus Land campaign, which fought to have local government develop 15 parcels of city-owned land into supportive housing for those experiencing homelessness. Although the campaign was successful in having the city set aside those parcels for that purpose, it turns out only two were ever developed: 150 Otis and 1100 Ocean Ave. Peter Cohen and Fernando Marti of the Council of Community Housing Organizations, an association of affordable housing developers in the city, explain that most of the parcels turned out to be too small and not viable for construction.

In addition, “the legislation applied only to sites owned by certain city agencies, and due to the city’s charter, did not apply to some of the largest agencies,” Martí says. Much of the land belongs to a constellation of independent agencies, such as the Municipal Transit Agency (MTA), the Public Utilities Commission (PUC), or San Francisco Unified School District. These agencies aren’t bound by city agreements related to property disposition.

Nonetheless, through community pressure directly on landowning city agencies, many other sites have become affordable housing, such as 2060 Folsom, which was owned by the PUC, or 4th & Folsom, which was owned by the MTA. Additionally, a number of sites such as Broadway Cove were reclaimed from freeway teardowns from the California Department of Transportation.

Unfortunately, due to recent budget cuts, agencies have been clinging to their unused land because it now is one of their biggest assets that can be used to provide needed capital.

The need is also much greater than it was in 2004, when the original campaign focused on developing supportive housing for the homeless. Housing is now such a widespread issue in the Bay Area that everyone is advocating for additional housing construction, though they vary in what approaches they prioritize. Because of this, Cohen says organizers looking to campaigns like 2004’s Surplus Land Campaign must be very clear and specific as to their goals and propositions to achieve them.

—Brandon Duong

|

These articles are free to read, but not free to produce. Please consider supporting our small and dedicated team on Patreon. |

Comments