B Lab co-founder Andrew Kassoy, at right, talks about shared prosperity and B Corps during a U.S. Department of Labor symposium, “The Future of Work,” held in December 2015. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Department of Labor via flickr

Almost a decade ago, more than a dozen businesses joined a movement to become the change they wanted to see in the world.

In a 2007 “coming out” party in California, 19 companies were officially recognized as B Corporations, which focus on using business as a force for good by making sure all stakeholders—customers, employees, and even the community—benefit from the company’s actions, rather than merely owners and shareholders.

Today there are more than 1,800 certified B Corps around the world and the movement has spread across dozens of countries and 130 industries. These are companies like Cabot Cheddar, which runs 46 percent of its farmer and plant operations in low-income communities; Badger Balm, a business that pays a living wage and provides every employee with a free home-cooked meal daily; and Ogden Publications, which ranks in the top 10 percent in the industry for using recycled products. Another 40,000 businesses are currently evaluating their companies to see how close they come to B Corp standards.

The growing B Corps movement is a step toward elevating the idea of the “triple-bottom line,” a term coined in the 1990s that refers to the measurement of a company’s social responsibility, its environmental impact, and its financial returns. But while there is growth in this still-young sector of business, can it become large enough to truly make a difference in the world? Will the push for living wages, the need for sustainable products, and the desire for economic stability within communities across the U.S. lead to continued growth for these mission-driven companies?

From Idea to Growing Movement

To become a B Corp, a company must first take what’s called the “B Impact Assessment” and score over 80 on a 200-point scale. The free assessment examines a business’s impact on workers, the local community, society broadly, and the environment. Businesses answer about 180 questions, such as:

• Do you offer parental leave, part-time or flex-time work schedules, or telecommuting positions?

• What percentage of your energy use comes from renewable sources?

• What percent of management are from underrepresented populations? Suppliers?

For small businesses, the assessment can take one to three hours to complete, but for larger companies, it could be a lot longer, according to the B Lab, the nonprofit company that certifies B Corps. (If a business does not reach the 80-point minimum score, the B Lab suggests steps it can take for improvement.) When a business has scored above the minimum threshold and that score has been verified, it must then meet the legal requirements to become a B Corp, which differ for LLCs and corporations depending on which state the business is located in. The requirements help ensure that a business’s mission can “survive new management, new investors, or even new ownership.” After those steps are completed, it’s time to sign a “Declaration of Interdependence” and pay a $500 to $50,000 fee, based on the company’s yearly sales.

B Corps must recertify every two years; the B Impact Assessment is also updated every two years. Almost half of all certified B Corps improve their scores over time, according to a recent report from the Abell Foundation.

Since the designation’s inception, the number of B Corps across the world has been slowly inching toward the 2,000 mark. About 40 to 50 percent of these businesses are outside the United States, according to Jay Coen Gilbert, a co-founder of the B Lab. Most recently there has been a lot of action in Latin America, specifically in emerging markets and low-income communities, Gilbert says.

A common misconception about B Corps is that most are larger businesses like Method, Patagonia, and Ben & Jerry’s, when in fact the vast majority are actually small and mid-sized companies.

Compared to the millions of businesses in the United States, the B Corps community might look like small potatoes. Even so, Gilbert and many others believe the business concept has already begun to make a difference in the world and will continue to do so. This belief is propelled by the passage of legislation in 31 states that allows a corporation to legally become a “benefit corporation.” The benefit corporation status provides legal protection for corporations to consider financial, societal, and environmental issues in their decision-making even if the company is publicly traded, according to benefitcorporation.net. While the B Lab helped develop the legislation and B Corps and benefit corporations are similar, they’re not quite the same.

Corporations can only become benefit corporations in states that allow that distinction. (B Corp status, on the other hand, is open to every business regardless of legal structure.) While the rules vary from state to state, generally corporations must amend their articles of incorporation to include the desire to create a “general public benefit” and assess their positive impact via a third party (which could include B Lab). Six years ago, Maryland became the first state to approve legislation for these types of corporations, and now more than 4,000 businesses across the country have legally become benefit corporations. That’s more than double the number of certified B Corps.

The passage of benefit corporation legislation in Delaware, where most U.S. corporations are incorporated, appears to be a pretty big deal, says Christina Hachikan, the executive director of the Social Enterprise Initiative at the University of Chicago Booth Business School. But until the concept is tested in the face of legal action, she questions the true value of the benefit corporation status. “You talk to three lawyers and you get four opinions about whether a benefit corporation is a good idea,” Hachikan says. “If you’re a benefit corporation and your investors want profits only, the only thing a benefit corporation document will do for you is state up front that you have the ability to prioritize other things. But ultimately, your investors own you and they can fire you, in theory.”

Hachikan says there needs to be court precedent that lawyers can point to that show benefit corporations on the winning side of the equation before more lawyers advise their clients to go that route.

Can B Corps Spur Economic Growth?

Certain characteristics are endemic to B Corps. Most pay employees a living wage (about 88 percent, according to Gilbert), offer good benefits, and understand the importance of family time. B Corps often make a point to hire and train vets, ex-offenders, and people with disabilities, and to work with local suppliers, all of which help support the communities in which these companies locate. In a July 2016 report from the Abell Foundation, Bringing the B to Baltimore: Using B Corporations as a New Tool for Economic Development, Michael H. Shuman argues that economic development authorities should actively work to bring B Corps into their respective municipalities.

The report indicates that if 100 companies in Baltimore became B Corps, it could create 120 new jobs and generate $450,000 of additional state and local taxes. “It would be cost-effective for state and local authorities to spend up to $450,000 over five years if they were confident it would lead to 100 B Corp conversions,” Shuman writes. “Plus they would effectively be investing $3,750 per new job—a bargain” compared to what is often spent in attracting companies.

In 2012, Philadelphia became the first city in the country to give tax breaks to B Corps. The city council adopted a $4,000 tax credit specifically for B Corps and similarly “sustainable” businesses, but the program was called problematic because businesses needed to have at least $2.8 million in total sales to qualify for the full credit. “Few eligible businesses actually obtain that level of sales,” the Sustainable Business Network of Philadelphia (SBN) said.

This summer, the council cleaned up the legislation so the tax credit can be applied against a business’s total income instead of only gross receipts. The change enables many more sustainable businesses to earn the full tax credit, which the council doubled to $8,000. The number of businesses that could participate in the program was also raised from 25 to 50 though 2018, and up to 75 in 2019. In another related bill, startups in the city can even earn tax-free status for the first three years of operation, says Maria Quiñones-Sánchez, the Philadelphia councilwoman who introduced the recently approved bills.

Michelle Long, the executive director of the Business Alliance for Local Living Economies (BALLE), applauds Philadelphia’s move and says that governments should incentivize B Corps and other small and local businesses because they bring more jobs to communities. According to the U.S. Small Business Administration, small businesses created 2 million jobs in 2014, double the number that large businesses created. Despite this statistic, the vast majority of economic development incentives—more than $80 billion annually—go to large corporations, Long says. (See The Answer) “Redirecting those incentives to instead be used for technical assistance for small businesses . . . and prioritizing communities of color, [has a] bigger opportunity for impact,” she says.

What’s Best for Your City?

Believing that the B Impact Assessment might be too cumbersome for smaller businesses, BALLE and the B Lab created a shorter version called the Quick Impact Assessment (QIA). “We eliminated some of the questions that were less relevant to smaller businesses and made it simple to take,” Long says.

Businesses across the country have used the assessment to measure their impact. In Grand Rapids, Michigan, business network Local First Michigan has helped many companies become B Corps by starting them off with the shorter and quicker QIA tool, Long says.

Last year, the New York City Economic Development Corporation, in collaboration with the B Lab, worked on a program called the “Best for NYC.” The program celebrated businesses in the Big Apple and invited them to take a version of the QIA that focused on low-wage workers and low-income communities, Gilbert says. Over six months, 600 businesses completed the assessment, 200 went on to become finalists (which meant they had to complete the full B Impact Assessment and get a verified score), and 100 finalists—some already certified B Corps—were selected as among the “best businesses for New York.”

“It’s a powerful and fun way to engage the business community around issues of justice without having to beat people over the head with it as a compliance task,” Gilbert says. “Those ‘Best For’ my city programs have greater potential to engage a much greater number of businesses, specifically around the creation of high-quality jobs for our most vulnerable citizens.”

Of the New York City companies that participated, Gilbert says, several changed their behaviors and practices. Some are now paying all their employees a living wage and others are exploring employee ownership opportunities.

The “Best For” program is happening in New York City again this year, as well as in 20 other cities throughout the country—some as big as Chicago, and as small as Arcadia, Louisiana.

“If you’ve got more businesses in your city that have a stated goal to create a more shared, enjoyable prosperity and they’re measuring their performances against that objective every year, that’s going to lead to better quality jobs because we know that B Corps are actually creating jobs at a higher clip than the rest of the economy,” Gilbert says.

Join the Fight? It’s Complicated

About 88 percent of B Corps pay their employees a living wage. If all companies behaved like B Corps, there would be between 12 million and 15 million more Americans who earned a living wage, according Gilbert.

Given this, JoEllen Chernow, director of The Center for Popular Democracy’s (CPD) economic justice campaign, says it would be interesting to get together with those companies to see how they could help promote the idea that increasing hourly salaries between $12 to $15 an hour is doable for businesses. CPD has been part of various campaigns across the country to raise the minimum wage and change the notion that businesses that increase employee salaries face dire economic straits. Seattle’s 2015 minimum wage increase was a great example. “It’s been good for businesses. The sky hasn’t fallen,” Chernow says.

Low-wage workers aren’t typically consumers or employees of B Corps like Patagonia, a high-end clothing and outdoor gear company that extends health benefits to part-timers and covers more than 80 percent of its employees’ benefits, she says. This might limit the power of their bully pulpit, because the “connection isn’t as direct,” says Chernow. However, she still sees some possibility in having B Corps tell their stories to CPD’s targets, which tend to be large corporations like Starbucks, Walmart, or McDonalds.

While there are businesses that have participated in movements like the Fight for $15, they’re not “banging down our doors,” she says.

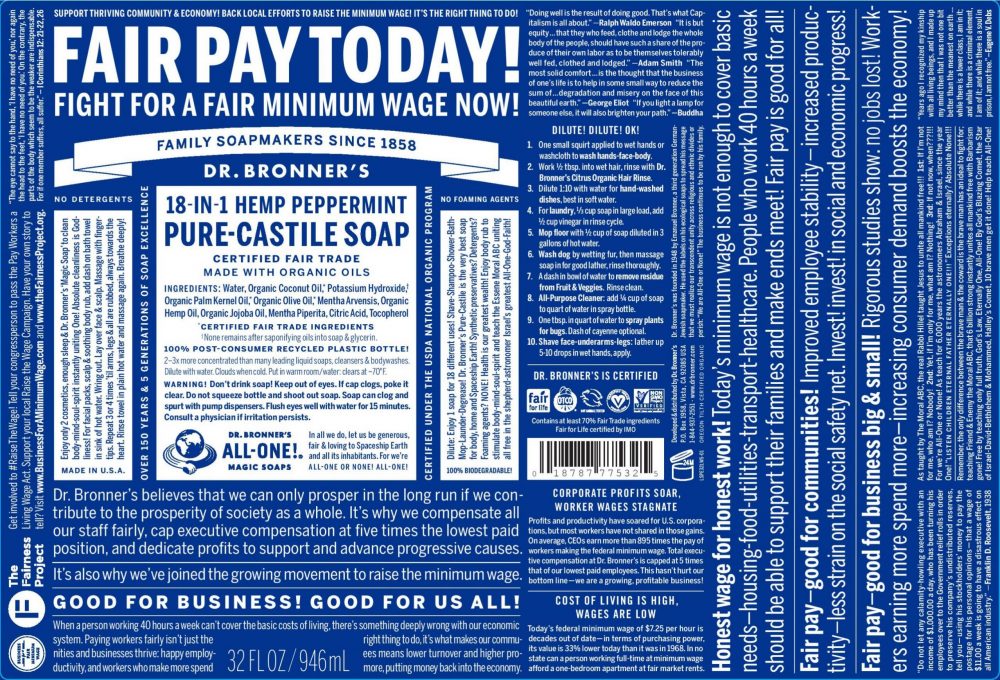

The “Fair Pay Today” label for Dr. Bronner’s 32-ounce peppermint soap. Photo courtesy of Dr. Bronner’s

Some B Corps have participated in minimum wage campaigns across the country. Dr. Bronner’s, a prominent B Corp based in California that pays its employees 25 percent above the living wage and covers 100 percent of their health benefits, joined the successful movement to raise the minimum wage in Washington, D.C. The campaign led to more than 120,000 D.C. residents earning a pay increase. On its 32-ounce peppermint soap bottles, Dr. Bronner’s changed its signature inspirational messages to include language about fair pay.

“I really think of those companies as natural allies,” says Ryan Johnson, executive director of The Fairness Project, one of the supporters of the D.C. minimum wage effort. “Probably more than any company I’ve ever interacted with, [Dr. Bronner’s] really walked the walk on social and progressive issues and they put their money where their mouth is.”

What advice would Johnson give to other organizations that are trying to partner with B Corps? “You need to frame . . . any partnership with not just ‘This is the right thing to do,’” he says, “but ‘This is also why it helps your business.’” It might not mean they get more money or sales directly, but it could mean that people will love or respect their brand that much more, he added.

B Corp New Seasons Market in Portland, Oregon, has also participated in a wage campaign. The grocery chain, which has 3,300 employees in more than a dozen locations in Oregon, Washington, and California, was under a tremendous amount of pressure to join the fight to raise minimum wages last year, Gilbert says. The company did raise its own starting wages from $10 to $12 an hour, according to The Oregonian, and also made a commitment to rally other businesses to support citywide and statewide raises.

But has the B Corps community as a whole engaged in these minimum wage campaigns?

They haven’t and it’s something that the B Lab grapples with, Gilbert says. There are some issues that B Corps are aligned on, but there isn’t 100 percent agreement on many controversial issues including the Fight for $15, carbon neutrality, or water or tax policy.

Taking a stance on one political issue likely means the B Lab would be asked to take stances on dozens of others, so it generally does not. Gilbert notes, however, that individual B Corps are free to join any movement they’d like.

Nonetheless, the B Lab did take its first stance on a policy issue this year when it moved its annual champions retreat from North Carolina to Philadelphia. Gilbert says the move was done because North Carolina passed HB2, an anti-LGBT law. It was the B Corp community that collectively decided to change the venue.

Gilbert says he understands that the B Lab has now opened the door to other requests. “It’s not never, but it can’t be every time,” he says.

B Corps: Looking Ahead

As the national conversation focuses more on the importance of reducing inequality, transparency will become extremely important for consumers who want to know how a company truly treats its workers. B Corps and benefit corporations, which publish a report of their overall social and environmental performance, may deliver on that goal.

Though the numbers of B Corps and benefit corporations will undoubtedly grow, Gilbert says, there isn’t a fixed target the B Lab wants to reach. “We’re trying to redefine success in business and change the culture of business,” he says. “This is generational change.”

For Johnson from The Fairness Project, the best outcome for the future is one where B Corps aren’t needed because their standards become the standards by which all business is done. “I think it’s going to have an impact,” says Johnson, “but I almost hope it impacts itself out of existence.”

This is a great article. I wish that it would be published in the New York Times, the Washington Post, and other major publications worldwide. It should be published as widely as possible. People need to know that there are alternatives to the usually sociopathic business model.

Great article, Lillian. I’ve never heard of B-corps before. I myself run an S-corp, a carpet cleaning business (https://www.torrancecarpetcleaners.com), where we try to pay our employees between 10%-20% more than the average wage for their positions and offer them good benefits. To me, what good is a company if they can’t even take care of their workers?

One can argue that paying higher wages would reduce a business’s earnings and make it harder to sustain itself and grow, but I think if a business is not earning enough revenue, employee wages are NOT the problem, but rather something else like weak product/service or weak sales.

This B-corps movement seems like a great way to incentivize businesses to pay their workers fairly. I think workers will appreciate that very much too and will end up being much more productive in the long run.