This article is part of the Under the Lens series

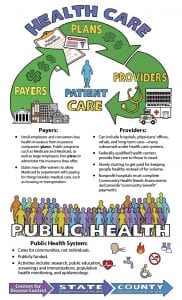

If there was one word to describe the U.S. health care system it would be “complex.” Or maybe “complicated.” “Convoluted” also comes to mind. Like the game Jenga, each piece—provider, payer, patient—is interdependent on the others. Pull one out and the whole thing comes toppling down.

Community developers have been increasingly told over the past several years that the health sector is exploring the social determinants of health and is interested in partnering with them on various initiatives, like expanding access to affordable housing. But finding a health partner requires understanding the different players and their financial and regulatory motivations.

Here is the 10,000-foot view of the U.S. health care system, with a focus on how the system is slowly shifting from one created to treat sick people to one that is learning how to keep them healthy and what that might mean for a community-based organization looking for a health sector partner.

Follow the Money: Providers

The U.S. spends $3.6 trillion on health care. That’s nearly $1 out of every $5 spent in the country, a figure expected to nearly double by 2028. In fact, we spend more per capita than any other industrialized nation in the world, and yet the quality of the care provided and the health of our population are among the worst of those nations.

So just where does that $3.6 trillion go?

Hospitals. About $1 in every $3 spent on health care goes to the nation’s 5,100 acute care hospitals. About 3,000 of those hospitals are not-for-profit, 1,300 are for-profit, and the rest are local, state, or federal government-run. Today, most hospitals are part of large health care systems, which may also own physician offices, home health providers, urgent care centers, and ambulatory care facilities, among other health care providers. This vertically integrated model enables the hospital to keep patients in its “system,” whether that’s lab and imaging tests, physical therapy, or outpatient surgery.

Physicians. About 1 in 4 health care dollars goes to the nation’s 486,000 primary care doctors and 535,000 specialists. Most are employed by health care systems under a salary structure.

Long-term care and rehabilitation facilities. These facilities provide care to the elderly and those who are not ready to go home after leaving the hospital. They receive about 13 percent of total health expenditures.

Prescription drugs. Despite rhetoric blaming them for the high cost of health care, prescription drugs make up only 9 percent—less than $1 out of every $10—of what is spent on health care.

|

The Public Health System COVID-19 has put the spotlight on the country’s public health system, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines as “all public, private, and voluntary entities that contribute to the delivery of essential public health services within a jurisdiction.” In other words, from the national level—the CDC—to the local health department, public health systems are dedicated to the health of a community rather than the individual. This can be seen clearly through the COVID lens as the nation’s public health entities take the lead in issuing guidance, and performing testing and contact tracing, among other services. Treating COVID-19 patients, however, is typically within the purview of the medical system. The 10 Essential Public Health Services

|

Follow the Money: Who Pays?

Unlike the majority of industrialized countries, the U.S. has no comprehensive health coverage for its residents. Instead, health care is paid for through a mishmash of private and public insurance. Despite numerous payer models, however, 8.5 percent (27.5 million) of Americans have no health insurance and must pay for all health care out of pocket.

Medicare. The largest health insurer in the country, Medicare is the federal program that covers all individuals 65 and older, as well as those with disabilities and end-stage renal disease (those on dialysis). Beneficiaries can opt for traditional Medicare, in which they can see any doctor who accepts Medicare patients; or Medicare Advantage, the managed care form of the program in which they are restricted to a network of providers but typically have a wider range of benefits—including, for example, hearing aids, and lower out-of-pocket spending. Overall, Medicare, whose policies are set at the federal level, covers nearly one in five (18 percent) Americans and is responsible for about 20 percent of all health care spending.

Medicaid. Medicaid is the federal/state program that provides health insurance to low-income people. Each state and U.S. territory designs its own programs (within certain federal guidelines) and determines who is covered. Traditionally, most Medicaid programs only covered pregnant women up to the first year after birth and children at or below the federal poverty level, as well as nursing home residents. However, that changed in 2010 with the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which provided significant federal funding to encourage states to expand coverage to those at higher income levels and to all adults under 65. To date, 37 states, including Washington, D.C., expanded their programs. In 2018, Medicaid paid for about 17 percent of all spending on health care.

Military health system. The military health system provides care for 9.5 million beneficiaries, including 1.4 million active duty and 331,000 reserve-component personnel and their families, and military retirees (through the VA or Veterans Administration).

The Indian Health Service. This federally funded program serves 2.6 million American Indians and Alaska Natives who belong to more than 500 federally recognized tribes in 37 states.

Federal and state marketplaces. The ACA created insurance exchanges to provide affordable coverage to people who didn’t qualify for or couldn’t access Medicaid, Medicare, or employer-provided insurance. It offers stipends to help pay for coverage depending on family income and provides four levels of coverage ranging from bare bones to Cadillac plans (each succeeding level requiring significantly more out-of-pocket spending). All ACA plans, as well as private, ACA-compliant plans, must adhere to certain regulations, including providing certain preventive health coverage with no out-of-pocket cost, covering preexisting conditions with no waiting period, and limiting overall out-of-pocket spending. So-called catastrophic health plans have no such requirements.

Employer-provided health insurance. The majority of Americans under 65 (about 67 percent) receive health insurance through their employer via commercial health insurance. In 2019, average premiums for an employer-sponsored family plan were about $20,000 a year, up 5 percent from the previous year. In 2018, private health insurance paid for about one-third of all health care expenditures in the U.S.

Consumers. Consumers, even those with health insurance, are paying increasingly more in out-of-pocket costs for their health care as employers opt for high-deductible plans and increase copayments and coinsurance. The average annual deductible among covered workers with a deductible has increased 36 percent over the last five years and 100 percent over the last 10 years.

Overall, consumers account for about 10 percent of total health care payments.

Plans

Health insurance companies operate in many ways. When working with small businesses and individual consumers, they collect premiums for a health plan they offer and pay providers directly under the terms of that plan. Large companies tend to be self-insured, and contract with a health plan at an insurance company to administer the program. Government agencies, like Medicare and Medicaid, also contract with health plans to administer their programs, generally paying a set fee (in the case of Medicare Advantage and most Medicaid plans) for each enrollee.

Some insurance companies, such as Kaiser Permanente, also run a health care system made up of hospitals, physician groups, and other health care providers.

Health plans often have a financial stake in the health of the populations they cover, particularly when, as is the case with Medicare Advantage and state Medicaid systems, they are paid on a capitated or other value-based basis. Thus, some health plans are partnering with community organizations to improve the social determinants of health.

The incentives are particularly strong for insurance companies that have a monopoly in a local market, since they can be confident that a community-based intervention will be reaching their customers. Health plans in competitive markets may see the value in advancing the social determinants of health, but be reluctant to support individual projects that might end up partially or primarily benefiting their competitors’ customers. They may, however, participate in collaborative efforts.

|

The Safety Net System Several programs are available to assist low-income individuals who don’t qualify for Medicaid or can’t afford private health insurance. They include: Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). CHIP is a publicly funded, state-administered program for children in low-income families that earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but don’t have or can’t afford private insurance. Today, the program covers 9.6 million children. Disproportionate share payments. These are extra payments the federal government provides to “safety-net” hospitals, which primarily care for uninsured or Medicaid patients. Federally qualified health centers (FQHC). These community-based health care providers receive federal funding to deliver primary and preventive care to more than 27 million underserved patients. They charge based on the patient’s income and ability to pay, often providing free care. They also provide free vaccines to uninsured and underinsured children. These providers include community health centers, migrant health centers, health care programs for the homeless, and health centers for public housing residents. |

Shifting Incentives for Providers

The U.S. health care system developed as one focused on disease and acute care, not health. With a fee-for-service payment system in which providers were paid based on how much they did, not on how well they did, there was no incentive to keep people healthy. Same with hospitals, which were typically paid on a per-diem rate, or a fixed rate based on the patient’s diagnosis.

All that is now changing, however, as the system moves from paying for volume to paying for value, i.e., high quality, cost-effective care. Today, the majority of hospitals and physicians are paid not on how much they do, but on how well they do it. Called value-based reimbursement, this approach incentivizes health care providers to keep a population healthy. The healthier the patient population, the greater the reward. Systems are also taking on risk—the sicker the population, the less they receive.

Under value-based reimbursement, providers might receive bonuses for meeting certain quality initiatives, such as healthy blood sugar levels in 70 percent of their patients with diabetes. Hospitals may lose money if they exceed a certain threshold of readmissions within 30 days of discharge or have a high rate of hospital-acquired infections. Hospitals and physicians are increasingly seeing bundled payment programs for surgical procedures like hip replacement or prenatal health care services, in which all providers involved share in a fixed payment.

Medicare led the way on value-based reimbursement—now more than 85 percent of Medicare’s payments fall under it, and private insurers and Medicaid are following suit.

This is a major reason health systems throughout the country are turning their attention to the social determinants of health.

Nonprofit health systems are also required to conduct Community Health Needs Assessments and report “community benefit” payments. Since the Affordable Care Act, fewer Americans are without insurance, freeing up community benefit funding that was once spent on care for the uninsured. These two requirements provide additional incentives to address social determinants of health, and opportunities for partnerships with community-based organizations.

The Social Determinants of Health

“U.S. public health leaders and researchers have increasingly recognized that the dramatic health problems we face cannot be successfully addressed by medical care alone.”

—Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014; 129 Suppl 2:19-31.

Just 20 percent of a person’s health is related to their access to health care; the other 80 percent depends on “the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.” These social determinants of health include such things as economic status, race, ethnicity, education, and environment, as well as health behaviors such as diet, physical activity, and smoking status.

As health systems take on increasing amounts of financial risk for the health of their communities, they are starting to address these factors. A recent review found that 57 health systems, which included 917 hospitals, invested at least $2.5 billion in community-based interventions between 2017 and 2019, with $1.6 billion focused on housing. Other areas included employment, education, food security, social and community context, and transportation. Nonprofit hospitals are required to provide community benefits to keep their tax exempt status, and under the Affordable Care Act the community benefits requirements were strengthened. Community benefits may include as free and subsidized care, public health initiatives, and programs to address the social determinants of health, including support of affordable housing and other community development programs.

A survey of 1418 hospitals conducted by the Association for Community Health Improvement and the American Hospital Association found that more than three-fourths of surveyed hospitals had partnerships with school districts and local public health departments.

The federal government is also supporting programs that target social determinants of health. For instance, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) developed the Accountable Health Communities Model, which provides support to encourage health care providers to partner with community services to address housing instability, food insecurity, utility needs, interpersonal violence, and transportation.

Such programs can pay big dividends. For instance, Geisinger Health System, which is based in Danville, Pennsylvania, and its health insurance plan provided healthy food to 95 Medicaid beneficiaries with uncontrolled diabetes who also experienced food insecurity. The beneficiaries also receive education about managing their diabetes. At the same time, 37 participants were also enrolled in Geisinger’s health plan and claims data for those patients showed a projected 80 percent decrease in average annual costs—from $240,000 down to $48,000 annually per member.

While the U.S. health care system has significant problems in terms of cost, quality, waste, and disparities, the past few years have brought some hope. Health systems—for-profit and not-for-profit, public and private—are increasingly recognizing that the underpinnings of health are not based on hospital beds and procedures, but on access to healthy food; safe, affordable housing; education; and transportation, among other social determinants. And, it appears, they are stepping up to improve these areas not just with words and reports, but with millions in funding. Understanding the players and their incentives can help community organizations form partnerships with these new potential allies.

|

|

The health of the community includes declaring racism as a hazard in all aspects of life in the community. And, the health of the community includes socioeconomic determinants of health, which involves a critical examination of the role economic policies at the local level have relating to impacts and outcomes. This includes redefining how civic success is defined by reviewing the community’s adopted long-term “vision”.