This article is part of the Under the Lens series

In March when Colorado declared a state of emergency due to COVID-19, the governor turned to the state health department’s Office of Health Equity to create a response team to focus on racial equity. It was clear then, and still is, that the virus was disproportionately harming people of color. Department staff convened a team of grassroots leaders and community organizers, almost all people of color, ensuring they had representation from rural, Native, queer, and disabled communities. The team met weekly to develop recommendations focused not just on stopping the spread of COVID-19, but also on building an equitable recovery and embedding racial equity into the state’s emergency response system.

How was the health department able to pull these partners together so quickly? Since 2007, the Office of Health Equity has been building collaborative partnerships with community organizers to address the root causes of health through its advisory commission and grant programs.

Our Theory of Change

Meaningful partnerships between public health departments and community organizers are incredibly important—they can build community power to create the conditions that allow people and communities to thrive. At Human Impact Partners (HIP) we’re working to transform the field of public health to center equity and build collective power with social justice movements.

One of our strategies is to build the capacity of public health agencies to act on the social determinants of health and advance health equity. Social determinants are the social and economic conditions that shape our health, which together have a much greater impact on health than medical care, genes, or our individual behavior. We use a definition of health equity adapted from University of California San Francisco health equity researcher Dr. Paula Braveman and her colleagues:

Health equity means that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible. To achieve this, we must remove obstacles to health—such as poverty, discrimination, and deep power imbalances—and their consequences, including lack of access to good jobs with fair pay, quality education and housing, safe environments, and health care.

We like this definition because it explicitly includes justice, and names power imbalances as a key obstacle to health. We believe that the unequal distribution of power, upheld by white supremacy and other systems of oppression and advantage, is at the root of health inequities.

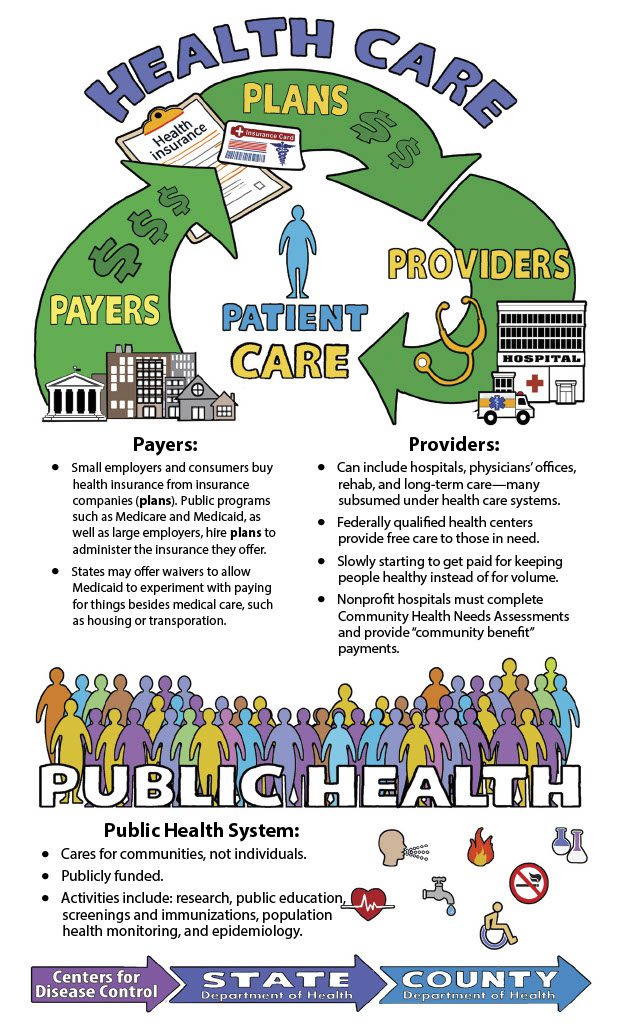

Why do we focus on public health departments? Partly because they are the backbone of the public health system, but also because we think they are uniquely situated to lead changes in how our government works. We developed a Health Equity Guide to highlight case studies from departments across the country, directed at a public health audience. But we know that for potential community partners, it can be unclear what exactly health departments do, and how their work might intersect.

What is Public Health?

Even with the COVID-19 pandemic underway, many people aren’t really sure what “public health” means. People covered in protective gear conducting drive-through COVID-19 tests might come to mind, but what else? The purpose of public health is to protect and improve the health of entire populations. It’s different from a medical approach, which focuses on individual treatment. A medical doctor working with a patient with heart disease might perform diagnostic tests, suggest more exercise, prescribe medication, or recommend surgery. In contrast, a public health approach tries to figure out how many people have heart disease, who is more vulnerable to it and why, and what kinds of policies or programs will prevent heart disease. Part of the reason that public health is often misunderstood and undervalued is that when it’s working, people aren’t getting sick, and so it tends to be invisible.

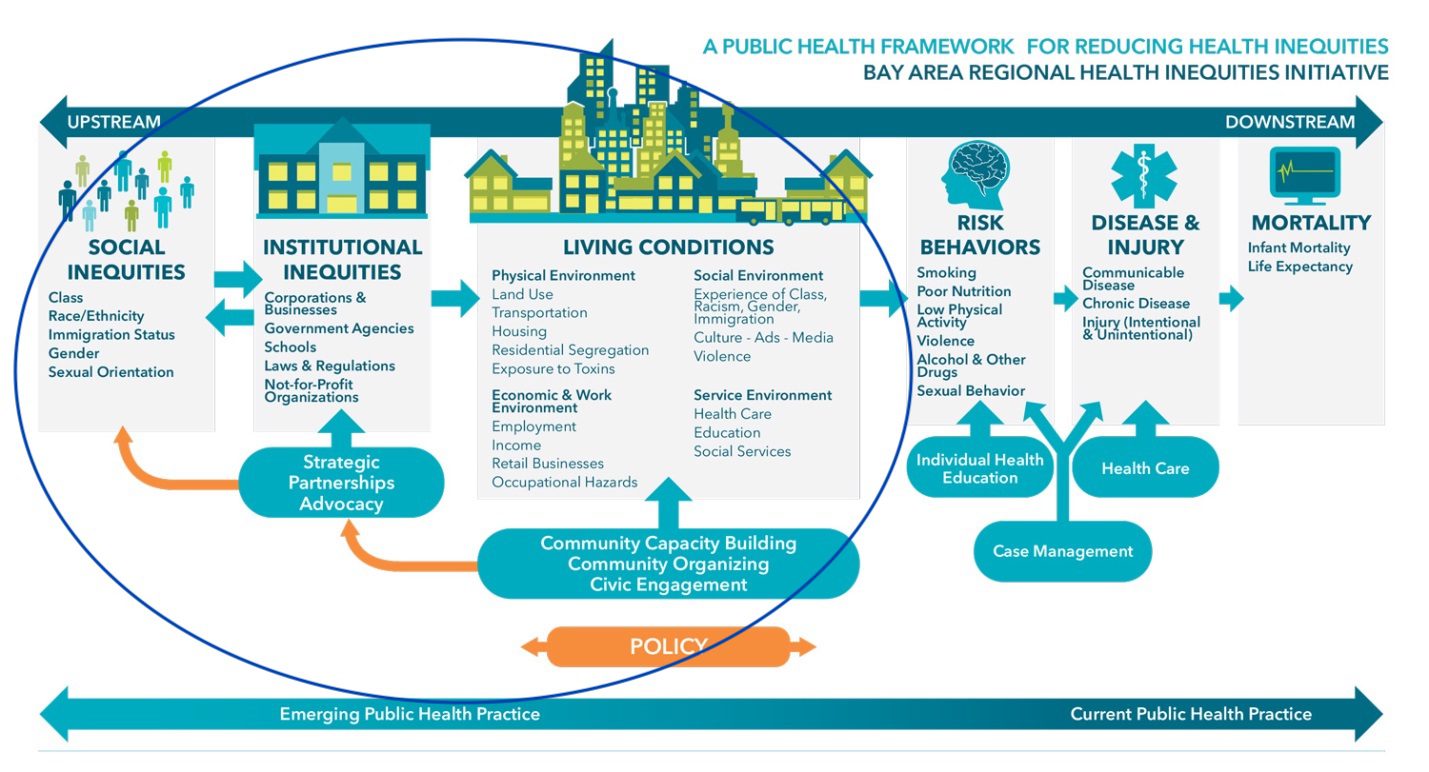

The Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative (BARHII), a collaborative of 10 health departments, has an excellent framework showing the drivers of health and health inequities.

The circle encompasses what practitioners call the “upstream” causes of health outcomes. While public health departments have become more comfortable working on some of the “living conditions” listed here—like transportation, housing, and occupational hazards—we need to go further to address the racism, sexism, institutional power inequities, and structural inequities underlying all those conditions to ensure that everyone—Black, Brown, and white—can be as healthy as possible.

It’s Time to Focus on Racism and Power

A focus on neighborhood conditions and housing is part of public health’s origin story. Governmental public health emerged in the 19th century in response to the unsafe and unsanitary living environments in urban working-class neighborhoods in England and the United States. It brought new regulations and an understanding that individual choices aren’t the only things that affect health, although the discourse was rife with anti-immigrant racism and hand-wringing about the morality of people living in poverty. As the scientific connection between germs and disease became widely accepted, public health shifted to a more individualized and medical model during much of the 20th century. The 1980s saw a renewed interest in social determinants, which gained strength with increased attention from the World Health Organization (WHO) in the 2000s.

Now, strategic plans and programs that name health equity as a priority are common in many health departments—and some are even incorporating an explicit focus on power. The WHO recognizes that “a lack of political, social, or economic power” is at the root of health inequities, and that interventions that address only the symptoms of power imbalances won’t be sustainable without broader systemic changes.

COVID-19 has shone a bright light on the connections between structural racism, inequitable living and working conditions, and health. Black and Latinx people are more likely to contract the virus because of multiple forms of racism and other systems of oppression and advantage. They are less likely to have jobs that provide safe work environments, and more likely to work low-wage essential jobs that cannot be done from home, that lack health protections or paid leave, and where employers have fought organizing efforts. They are more likely to live in crowded housing that provides few opportunities for distancing. Racism embedded into the immigration enforcement and criminal legal systems means Black and Latinx people are more likely to experience policing and incarceration, practices which spread COVID-19.

Black and Latinx people are also more likely to die of the virus, an inequity that persists when controlling for income. Structural racism and other systems of advantage continue to create inequitable living conditions and the higher rates of underlying health conditions that increase risk of death from COVID-19. Native American communities are also being hit hard by COVID-19, even though data collection fails to accurately track these cases. In the face of these glaring inequities, and in response to the recent uprisings protesting police violence against Black people, some health departments and cities have moved to declare racism a public health crisis.

What Do Public Health Departments Do and How Do They Work?

Public health departments exist at multiple levels: local (city or county), state, and federal. Every state has some local health offices that are either run by county or city government, or overseen by the state. To find the department working where you live, check out the National Association of County and City Health Officials’ (NACCHO) Directory of Local Health Departments. To get into the weeds of who has authority over local public health decisions in your state, take a look at this classification system from the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO).

Local departments are then further split up into divisions or programs, which vary from place to place but tend to include some combination of:

- Community health—prevents chronic disease by engaging communities in issues like healthy eating, exercise, and tobacco use.

- Emergency preparedness—develops plans to mobilize staff, supplies, and activities in response to natural disasters and pandemics.

- Environmental health—works to eliminate hazards in food, water, homes, and workplaces, issues permits, e.g., to restaurants and tattoo parlors.

- Epidemiology—collects, analyzes, and publishes data on disease, injury, and their causes.

- Infectious or communicable disease—runs programs focused on vaccination, vector (e.g., mosquito control), sexually transmitted infections, and tracking outbreaks.

- Injury and violence prevention—works to prevent opioid overdose, motor vehicle injuries, and interpersonal violence.

- Maternal and child health—provides services for pregnant people, infants, and young children, such as home visits, breastfeeding, and nutrition support.

Funding and Accountability

Public health spending represents less than 3 percent of total health spending in the United States, and health departments have faced steep cuts since the Great Recession of the 2000s, a problem that’s been thrown into sharp relief as they struggle to respond to COVID-19. They rely on multiple federal funding streams, most of which are categorically focused on specific health outcomes. About half of funding for all local departments combined comes from state and local sources, and about one-quarter from federal public health sources. The remainder comes primarily from Medicaid and service fees (e.g., inspections). One percent of overall funding is from private foundations.

Health departments are accountable to the governing body in their jurisdiction—the city council, county board of supervisors, or state legislators. They also report to federal and state agencies that fund them. However, as public agencies, health departments should ultimately answer to the people they serve—and community partnerships are one way to build that accountability.

Departmental Culture Varies Quite a Bit

Culture and capacity are different from one department to another. Some have long-standing, deep relationships with community partners, a strong focus on health equity, and a culture of creativity and innovation. As with most institutions, this often depends on leadership. At the Cook County Department of Health in Illinois, Dr. Linda Rae Murray, who served as the chief medical officer from 1997 to 2014, explicitly centered health equity through national leadership positions, interviews in local media, and learning opportunities for staff who wanted to prioritize equity in their work. Her public commitment to health equity and support for passionate staff members helped spur the department’s participation in a local collaborative where they’ve worked with community organizers on economic and immigrant justice campaigns.

Even with bold leadership, governmental culture can be slow and risk averse—especially from the perspective of organizers who are used to springing into action around a campaign—which is something potential partners should be prepared for.

Agencies Have Incentives to Partner with Community Organizations

Many people go into public health because they’re motivated by social justice, including people who have experienced injustices in their own communities. They understand that the field can’t address injustice without centering the people who experience it most directly. In the words of Dr. Rex Archer, the director of the Kansas City Health Department: “Change in the form of community mobilization and policy development comes when the folks who are actually harmed by the issues are engaged and empowered to have a voice.”

Archer sought out new partners because he knew he couldn’t address the city’s life expectancy gap between Black and white residents by sticking to business as usual. In 2007, he began attending meetings of Communities Creating Opportunity (CCO), which formed in the 1970s to address residential segregation. Since then he has been organizing on racial and social justice. This spurred a long-term partnership between the health department and CCO, which was eventually formalized in 2012 through a memorandum of understanding and even shared office space. The department and CCO regularly come together to identify priority health issues and develop strategies to tackle them, and this partnership has helped normalize a focus on social justice within the department.

Partnering with organizers makes it possible for the department to use an inside/outside strategy, in which people working inside and outside of government use their differently situated power to achieve a shared goal. Organizers can often use bolder advocacy and tactics, while department staff can navigate government date gathering, decision making, and authority. In Cook County, health department staff partnered with organizers via a coalition external to the department, giving them an opportunity to support campaigns that may have been considered “too risky” for the department to take on directly. As coalition members, staff provided data for fact sheets in support of local immigrant rights ordinances, and helped craft advocacy materials calling on the governor and state health department to address unsafe conditions at immigrant detention centers amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Kansas City, when the health department was working to establish a Healthy Homes Rental Inspection Program, department staffers drew on their relationships with organizers to build broad support for it. When the ordinance to create this program didn’t pass the city council, those organizers orchestrated a ballot initiative that ultimately put an even stronger program into place.

There are also external incentives for community partnerships. State and local department accreditation requires engaging partners in developing a community health assessment and plan. Some grants require partnerships, which can help fund community organizations in their work with health departments (more on that later!). Finally, many of the departments discussed here have received awards and prizes for their work incorporating community power building—which can bring not just recognition but greater buy-in across the department.

Editor’s Note: In the second part of this piece, we take a look at examples of what health departments bring to the table in partnerships with community organizations, and offer tips for building a relationship with health department staff in your area.

|

|

These efforts are great but they do not go far enough. Unless/until public health depts collaborate with CED practitioners who seek to replace the structural determinants of our widening socioeconomic divide, the status quo will remain. “Health equity” from my experience is still limited to the public health arena, w/o any real interest in economic public policies which determine “success” or failure; policies are deterministic. We need deeper intersectionality.

I live in the poorest urban city in the U.S., which is San Antonio, Tx. I’ve attempted to reach out to the public health network to some degree to seek a common agenda, seeking allies in dealing with the dominant “urban planning” model of civic “success”, which excludes community well-being, & prizes the built environment & a metroplex agenda. Far more needs to be need in this regard; land scarcity leads directly to impoverishment for low & moderate income communities. Health issues get a lot of attention but the point of the spear of inequity is left unrecognized. Become pro-active not reactive.