By now, the $1,200 stimulus checks have long since been spent. Although over 30 million Americans may be currently out of work, the $600/week extra unemployment payments ended, and Republicans in Congress oppose reinstating that benefit. Federal eviction protections (other than a recent limited public health order), and most state moratoriums, expired in late July. As a result, predictions range from 28 million to 40 million tenants at risk of evictions in the coming months, which is about 25 percent of America’s renter population. Displacement on that scale would vastly dwarf the roughly 3 million foreclosures of 2009 when the country plunged into a deep recession.

The best governmental responses to this impending disaster would be extending income benefits to unemployed Americans, providing special rental subsidies to protect tenants and support landlords, and continuing eviction and foreclosure relief.

While some states and localities are stepping up to meet the need, this support will fall vastly short of the estimated $100 billion needed. And when tenants can’t pay rent, landlords can’t pay mortgages, local taxes, or the operating expenses that allow homes to be well maintained and habitable.

This means, without federal action, there likely will be a huge wave of real estate defaults, workouts, distressed sales, and foreclosures. It does not take a crystal ball to see an impending real estate downturn.

Private Capital Is Waiting

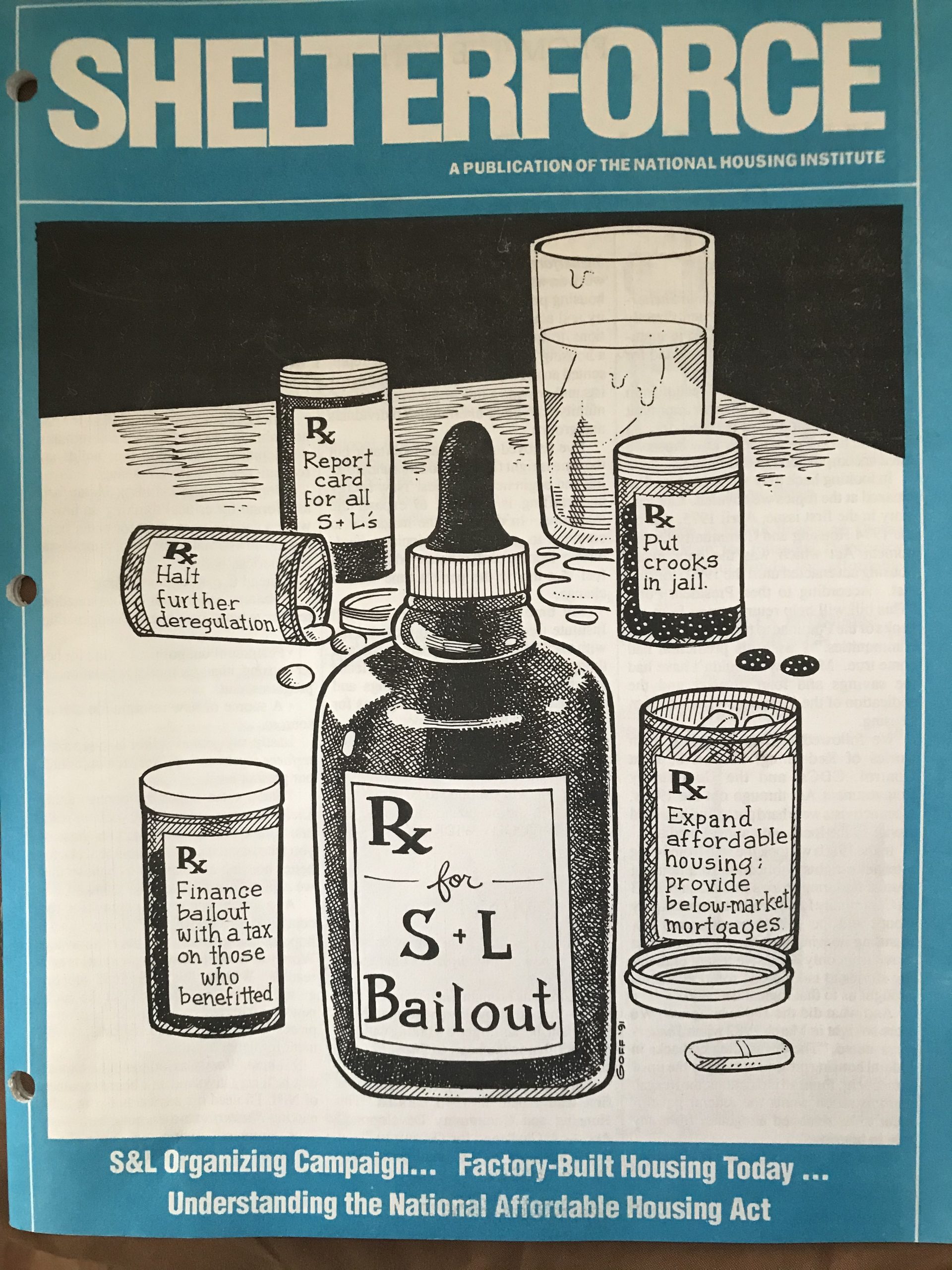

History has taught time and again, such as during the Savings & Loan crisis of the late 1980s and the Great Recession’s foreclosure crisis of the late 2000s, that private actors stand poised to deploy capital to leverage buying opportunities when properties pass through public hands. Far too often, public agencies fail to take the long view of assets they control, or consider prioritizing public needs when developing disposition plans. Public purpose and broad mission carry little sway against the pressure to minimize current losses and reduce property inventory counts. Yet a short-term focus fails to serve the larger goal, and likely leaves society worse off in the long run.

The Savings & Loan banking crisis, for example, combined with a real estate recession, led to tens of thousands of rental units going into foreclosure. As the federal Resolution Trust Corporation began selling off real estate assets assembled from 747 collapsed savings banks, it missed the opportunity to create permanently affordable housing in the thousands of apartment buildings across America that it controlled. Hundreds of billions of dollars of public investment into failed banks could have been converted into a meaningful affordable housing program. Instead, well-capitalized, for-profit investors moved nimbly to buy apartment buildings from the public at a deep discount and realized huge profits when the market recovered.

Similarly, during the Great Recession foreclosure epidemic, public agencies again acquired a growing inventory of real estate, this time foreclosed single-family homes in thousands of low- and moderate-income neighborhoods. Despite the efforts of a coalition of housing and community development organizations to create the Great American Dream Neighborhood Stabilization program—which would have sent $20 billion of funding to in-community nonprofit stewards who would buy properties at or out of foreclosure—what emerged from Congress was the Neighborhood Stabilization Program. But that program’s funding levels fell far short of the need and burdened community buyers with restrictions that slowed the use of the funds. Because of these limitations, predictably, once again cash-rich private investors moved more quickly to acquire portfolios of properties. In many cases, profit-focused buyers turned out to be shoddy landlords, renting out homes already in poor condition while shifting maintenance burdens on to unsuspecting cash-strapped tenants. This hurt hard-hit communities that could have instead benefited from short-circuiting the vicious cycle of falling property values and staving off the negative effects of increasing vacancy while creating a stable pool of affordable homes.

In the current moment, we must be ready to respond even if only a fraction of distressed rental properties move into the foreclosure process. Roughly 7.5 million homes are in 2- to 4-family buildings, and over 13.7 million homes are in 5- to 49-unit buildings, with roughly 7 out of 10 such properties owned by smaller “mom and pop” landlords. This accounts for over half of the rental homes in the country. If only half of these 21 million apartments are unstable in a downturn, and only 10 percent of those actually end up in default or foreclosure, that would still represent over 1 million apartments potentially coming to market. Already, roughly 1 in 6 smaller apartment properties are non-performing (delinquent, in foreclosures, or have mortgages in special servicing).

History teaches us that to get ahead of the curve, we need a flexible source of capital, combined with a system for turning distressed properties into affordable ones. We need to create a Stabilization Acquisition Emergency Fund (SAEF) to expand the national stock of decent rental housing that’s affordable for the long term.

Let’s Do It Right This Time

A SAEF approach would flow low- or no-cost capital to mission-based organizations with capacity to acquire and manage rental housing. The target acquisitions would be existing privately owned properties where owners facing rent loss and/or potential mortgage default are willing to sell as an alternative to foreclosure, or where the owner otherwise wishes to exit. Ideal properties would be those where a combination of low debt service and below-market returns would translate into rent relief for tenants. A second class of properties coming into the market are hotels and motels being repositioned for rental housing. California has taken a lead on this, allocating $600 million to groups converting hotels and motels into housing for homeless people. But private sector funds and developers are seeing the same opportunity and will have the market advantage through greater access to capital and fewer regulatory constraints, unless there is a SAEF infusion of funding to community-based organizations (CBOs).

There are many critical details to work out in creating an effective SAEF program, but we propose four central principles to guide any plan:

- Affordable—The beneficiaries of SAEF are the tenants. The program must be designed to encourage maximum affordability by minimizing the cost and complexity of acquisition capital. Grant funding, or no-interest loans that are ultimately forgiven if affordability is maintained, will build into program structure savings that nonprofit owners can pass along to tenants in the form of affordable rents.

- Frictionless—The more layers between appropriation and purchase, and the more regulatory burdens placed on CBOs, the less likely SAEF buyers will be competitive.

- Durable—Short-term funding puts inordinate pressure on buyers to have more complicated “take out” funding in place before buying. SAEF should ideally have a loan term of 10 years or longer.

- Adequate—SAEF must be funded at a level sufficient to acquire enough properties to make a significant increase in our affordable stock. It should provide a single source for both buying and near-term renovations.

The adequacy equation also includes the amount of funding per unit needed for an effective SAEF program. Though prices per door for so-called “naturally occurring affordable housing” vary enormously across the country, in most places, apartments can be purchased for less than $100,000 each. However, such properties often have deferred maintenance and capital needs, particularly those in financial distress. We would propose at least an additional 10 percent over the purchase price be included for immediate renovations and capital needs, along with another 5 percent for due diligence and administrative costs. At this level, a national program sufficient to acquire 500,000 apartments per year would require up to $57.5 billion in funding.

Past downturns have revealed that CBO buyers inevitably compete with for-profit organizations that have built-in advantages—they can pay all cash and quickly, while affordable buyers typically patch together multiple, complex sources of funding, which results in slower closing times. This disparity strongly incentivizes sellers looking to get out from under a difficult situation to choose for-profit investors over affordable buyers.

We know that when a crisis is perceived, government funding streams can move quickly. For SAEF to work, nonprofit buyers in affected communities must come to the table able to write sellers a single check from a single source.

For this reason, we propose routing SAEF funding through the Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) system. Designing an effective program requires a careful balance between responsible regulations on the use of public funds while not hamstringing CBOs with overly burdensome regulatory constraints that put them at a disadvantage to market-rate investors. The CDFI system is well adapted to address this concern, as CDFI lenders already have a track record of responsible underwriting of affordable housing, as well as experience lending to small businesses. The two prime CDFI funding vehicles—CDFI Financial Assistance, and Capital Magnet Fund—each have pros and cons as a way to get SAEF funding quickly and efficiently to the local level, and any SAEF appropriation may require some modification of the programs to fit the crisis need.

As to affordability, we recommend requiring affordable rents, not income certification. Tenants in “naturally occurring affordable housing” have a range of incomes. Not all tenants will initially fit easily in the standard affordable housing subsidy program income limitations. SAEF can most quickly and effectively achieve the goal of expanding the stock of housing by focusing on setting rents at levels affordable to low- and moderate-income renters generally. More stringent rules requiring income-certifying all residents will both shrink the market and put pressure on owners to displace residents who may need an affordable place to live but find themselves above the standard limits, or cannot easily document their income for various reasons. And getting properties into the hands of mission-oriented affordable housing nonprofits is in itself a vital public purpose.

We have the opportunity to get it right this time as a downturn looms on the near horizon. Real estate runs in cycles, and those who take advantage of down cycles profit in the long term. Lessons from past downturns need to inform a broad-based policy approach to the next downturn. It is time for the public to take a lesson from the private sector and line up the capital and the strategy today to be ready to buy tomorrow and generate public benefit for years to come.

Thank you for your detailed article clearly indicating that a tsunami wave of evictions and foreclosures is coming in the not to distant future. I’ve been through this cycle before and you are spot on regarding planning now.

Your idea of naturally occurring affordable housing is interesting and has the benefit of eliminating the relocation costs nightmare but it brings with it those who make more than needed to pay the new more affordable rent, while thousands need that unit with their low income.

This is a bold and thoughtful proposal. It can be complemented with the ongoing local and state efforts around the country to enact Tenant Right of Frist Refusal and Tenant Opportunity to Purchase legislation. While preserving naturally occurring affordable rental housing would be a tremendous outcome, the combination of SAEF funding with TOPA presents an opportunity to re-energize the housing cooperative movement in the country