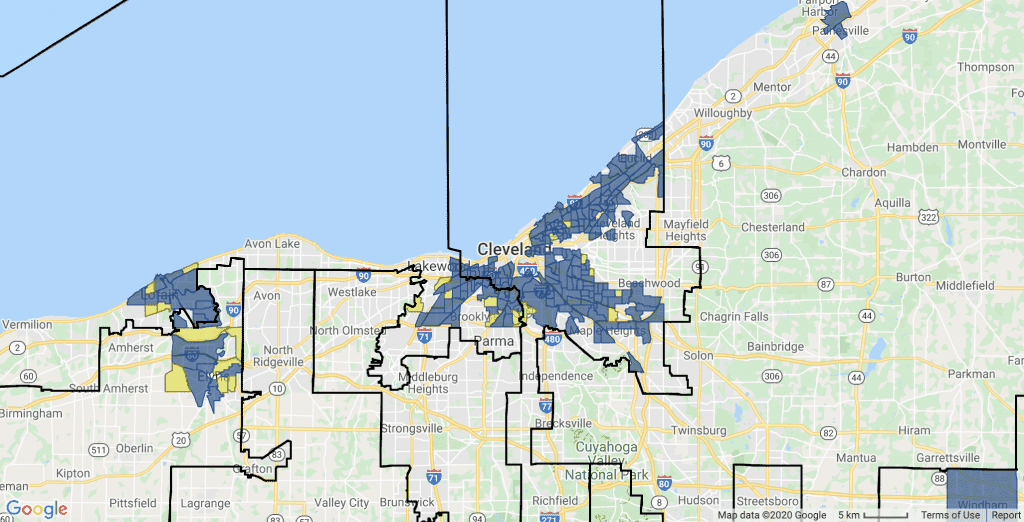

A map shows census tracts in Cleveland that would be eligible for NHIA funds if legislation were to pass. Courtesy of the National Community Stabilization Trust

It is easy to get discouraged by the flood of bad news, from the spread of COVID-19 to rising rents and racial disparities. Not all the housing news is grim, though. While stories of congressional dysfunction get lots of media attention, there are examples of bipartisan, practical problem solving occurring on Capitol Hill right now. We’ve seen recent actions in both the House and the Senate that show some real momentum behind the Neighborhood Homes Investment Act (NHIA), legislation that creates a tax credit to spur investment in modest single-family homes in distressed neighborhoods. These communities were left out of the recovery from the last Great Recession and could be at risk in the current one.

In July, a bipartisan group of senators, including Sens. Ben Cardin (D-MD), Rob Portman (R-OH), Chris Coons (D-DE), Todd Young (R-IN), Tim Scott (R-SC), and Sherrod Brown (D-OH), introduced S. 4073, the Neighborhood Homes Investment Act, a companion to H.R. 3316, originally introduced by Reps. Brian Higgins (D-NY) and Mike Kelly (R-PA). Also in July, the House passed the legislation as part of broader infrastructure legislation, which is now pending in the Senate. Prospects for the infrastructure bill are uncertain at present, but there may be an opening after the general election in November. In addition, former Vice President Joe Biden’s presidential campaign also endorsed this legislation as part of a plan to promote racial and economic equity.

[Related: Single-Family Subsidies are Needed Outside Hot Markets]

What is prompting an ideologically diverse group of members of Congress and a presidential campaign to come together to support new resources for housing? They are motivated by the lack of suitable housing supply and the problem of neighborhoods plagued by substandard housing and vacancy. In many communities across the country, the cost of renovating or building homes exceeds the price the homes can be sold for. This discourages mortgage lending in these communities, which limits the availability of homes that are affordable to first-time homebuyers.

This valuation gap can also lead to further dilapidation and vacancy. Homeowners can’t get loans to keep their homes in good repair, and potential homebuyers can’t find homes that are move-in ready. Without new and newly renovated housing, neighborhoods lose the opportunity to be rejuvenated and cities lose an important source of tax revenue, leading to a deterioration in municipal services. It’s a downward spiral that is preventable.

It is worth noting that the U.S. housing stock consists of mostly single-family homes, and 40 percent of this housing stock is at least 50 years old, so repair needs are accumulating. Aging, substandard homes are prime candidates to become vacant and abandoned. Vacancies persist in many market even as foreclosures decline—there were 3.7 million vacant properties in 2005 but 5.8 million in 2016, according to report by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Recent research notes, “There are a substantial number of weak-growth metros in the Sunbelt, especially outside of California and Florida, in which very high levels of vacancy have remained a problem even in the face of a broader national recovery. In the Sunbelt, and in particular the Rust Belt, neighborhoods with very high and, especially, extreme vacancy rates tend to have large Black populations and high poverty rates.”

NHIA creates a tax credit allocated by the states that covers the gap between the cost of construction and the sales price of the home if the home is sold to an owner-occupant who earns under 140 percent of the Area Median Income. It is modeled on the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), which is also allocated by the states and has a 30-year track record of spurring the construction of affordable apartments.

The homeownership tax credits in the NHIA can only be used in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods for modest homes. This interactive map shows where NHIA can be used—it is targeted to census tracts with lower home prices, lower resident incomes, and elevated rates of poverty. States will develop allocation plans that award the tax credits to developers or lenders with successful track records of building or renovating single-family homes. This is a cost-effective approach to the problem of a lack of quality housing supply because the tax credits cover only the gap between construction costs and sales price.

Homeowners will take out mortgages to finance their homes, and over time this approach should help stabilize real estate markets previously dominated by distressed sales. As with the LIHTC, private investors will bear market and construction risks, and the credits will only be awarded when the homes are sold to qualified homebuyers. This innovative tool will increase the supply of affordable housing so first-time homebuyers can take advantage of historically low interest rates now.

Finally, NHIA can contribute to closing the homeownership gap for people of color because it increases the supply of move-in-ready homes in neighborhoods with large populations of Black people, Indigenous people, and other people of color. Shockingly, the gap between White and Black homeownership rates is nearly the same today as it was before the Fair Housing Act passed in 1968. There are many causes for racial disparities in homeownership—discrimination in lending and employment, lack of intergenerational wealth, and unequal access to credit—and they all need to be addressed, but NHIA addresses the lack of affordable homes for purchase. NHIA will allow homes that would otherwise sit vacant and dilapidated to be turned into a resource to help families build wealth.

The NHIA has been endorsed by a broad coalition made up of housing trade groups, including the Mortgage Bankers Association, state housing finance agencies, and nonprofit housing developers like Habitat for Humanity. This is a bipartisan, market-driven approach to the national problem of an aging single-family housing stock that will otherwise continue to deteriorate. Let’s stop high levels vacancy and substandard housing before they spread further.

Thanks you!

Are there anti-displacement safeguards in this bill?

Wouldn’t it make sense for this program to also encourage if not mandate weatherization, and high-efficiency appliance replacement? (heat pump, induction cooktop, high-efficiency lighting, hvac, etc.).

I don’t doubt that creating a tax credit for developers will spur investment in some dis-invested communities and lead to lower vacancy rates, less “blight,” higher property values, etc. But I think the claim that the NHIA will “increase the supply of affordable housing” is deeply misleading and the idea that it will “[close] the homeownership gap for people of color” simply by increasing housing supply in the neighborhoods where they live is either naive or optimistic in the extreme. On the face of it, the proposed legislation looks more like it’s poised to become yet another entry in the long list of federal housing policies whose primary beneficiaries are private developers and middle class white families.

In Philadelphia, where I live and work for an affordable housing developer, many census tracts that would likely qualify for NHIA credits include gentrifying neighborhoods where a demographic snapshot showing a low-income community of color would belie the ongoing displacement crises and gradual transformations taking shape. The 2020 Area Median Income (AMI) for the Philadelphia area is over $96,000 for a family of four, even though in the city itself the AMI figure is barely $40,000 and in many neighborhoods the average household earns less that $25,000 a year. Allowing for purchases by households up to 140% of AMI, NHIA’s proposed income eligibility guidelines would allow a first time home buyer earning over $134,000 – more than three times the city’s AMI and more than five times the AMI of households living in neighborhoods from Grays Ferry to Mantua to Nicetown to Kensington – to buy a federally-subsidized “affordable” home in a low-income community.

I put “affordable” in scare-quotes here because, unless any resale restrictions (a la a community land trust) are put in place to ensure that the renovated home remain affordable, then the program is actually just giving one generation of homeowners an affordable home and opportunity to build wealth in resale while, in the medium-to-long term, only increasing the supply of market-rate housing. Then, when we then take into consideration the facts of the racial wealth gap and the ongoing racial discrimination in mortgage approval for equally qualified buyers (aka redlining) in Philly and across the country, we’ll find that the population of people most likely to actually make it to the home buyer finish line and acquire these properties is going to skew wealthier and probably whiter than the average demographics of the neighborhoods where they’re buying (aka gentrification).

I can’t speak to the dynamics of rural communities that could be impacted by the proposed NHIA, but from the perspective of middle- and weak-market cities, it’s easy to see why a bipartisan coalition of overwhelmingly white male millionaires (aka Congresspeople) would support the initiative: because they can claim to be supporting legislation to help low-income communities and those of color while actually working to line the pockets of developers and give middle class white families a federally subsidized step up into gentrifying neighborhoods. As we face down the generational crisis catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic and uprisings against systemic racism, housing advocates and community development practitioners have a clear responsibility to do better than this.

Great article, Kris! I work in low-income and middle-income neighborhoods across the country, and everywhere there is older, affordable housing stock dying on the vine because the numbers do not work to rehab it. In a market with such low inventory of affordable and move-in-ready homes, this is a travesty. Furthermore, whole neighborhoods are slowly declining because every year, their housing stock is more out of date and less able to compete for today’s homebuyers – all for lack of capital to cover appraisal gaps and to begin pulling neighborhoods out of their downward spiral. In most of America, gentrification is not a current or potential risk. For these neighborhoods, either we reclaim the housing stock and update it for the next few generations of homebuyers, or we lose it all to deferred maintenance, bottom-feeding investor landlords, tax delinquency, foreclosure and vacancy. The intervention in these neighborhoods gets more expensive the longer we wait. The time to act is now.

Obviously, every locale is different. In the very low income minority community in which we work in Memphis, this would probably work. The neighborhood’s in little danger of gentrification; there are many houses that are not in condition to be bought by home owners, but the investment gap makes it hard for us to acquire, renovate and resell. We need tools to compete with out-of-state investors.