Photo by Cragin Spring via flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0

We are in the midst of the greatest affordable housing crisis in American history. Even before the pandemic, increases in rents and home prices in urban areas outpaced the increase in wages for most working families. Now, pandemic-induced unemployment is about to cause more people to lose their homes, and many more tenants to be evicted. This severe and persistent crisis calls for a new approach to the provision of housing.

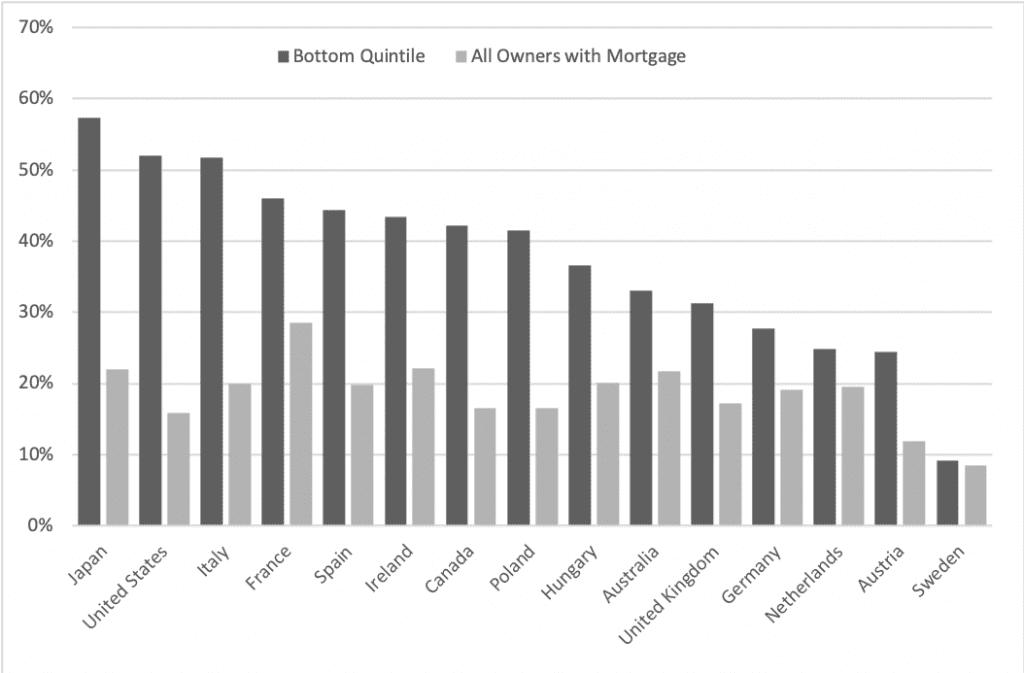

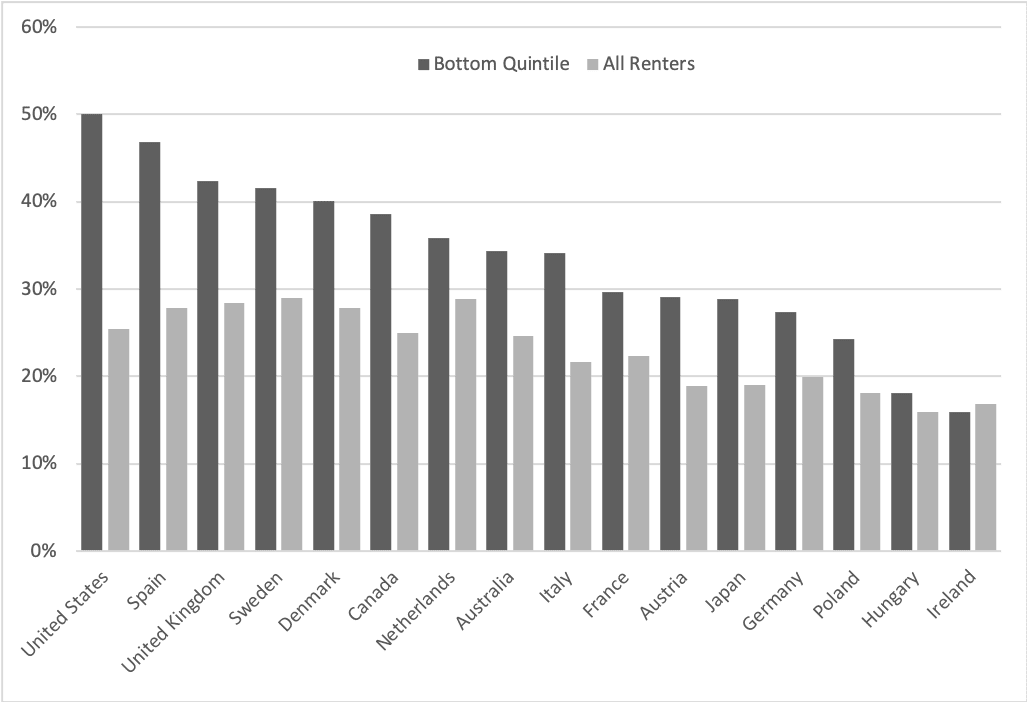

Housing in the United States is uniquely inequitable, even among advanced countries. Data for OECD nations show that the U.S. has one of the highest housing cost burdens in the bottom quintile, in which the median household is spending over half its income on housing, whether it owns (Figure 1) or rents (Figure 2). The U.S. has the largest gap in housing cost burdens between the bottom and middle-income quintiles for a median household in the private market, including those with subsidized rents. Yet many of the essential workers who keep our cities functional even during a health emergency are at the bottom of the income ladder. These cost burdens affect owners and renters alike, particularly millennials looking to enter homeownership. The future of the American city itself is at stake.

Figure 1

Figure 2

“Unhousing” the Public Sector

Unfortunately, the old housing finance model is fragmented and marginal at best. Almost half a century of neoliberal dominance over the U.S. housing policy has yielded no permanent solutions, only moved the problem around and made it worse for most Americans. Neoliberalism is a laissez faire economic philosophy that pervades U.S. political, social, and moral spheres. Couched within the mantle of personal freedom, neoliberal policy aims to loosen political control over economic actors and markets, replacing regulation and redistribution with market freedom and uncompromised ownership rights, according to University of California Berkeley professor Wendy Brown. Brown argues that neoliberalism constitutes an attack on democractic institutions, society, and social justice.

One of the key intellectuals behind neoliberalism was economist Milton Friedman. In a 1993 essay titled “Why Government Is The Problem,” he blamed the high cost of housing on “building regulations, zoning laws, and other governmental actions.” Echoes of this neoliberal argument are pervasive in housing policy today. In his seminal work, Capitalism and Freedom, published in 1962, Friedman argued that homelessness is caused by rent control and public housing:

“Public housing cannot be justified on the grounds either of neighborhood effects or of helping poor families. It can be justified, if at all, only on grounds of paternalism; that the families being helped ‘need’ housing more than they ‘need’ other things but would themselves either not agree or would spend the money unwisely.”

Although he thought discrimination was distasteful and expensive, Friedman opposed civil rights laws as an infringement of an individual’s right to contract. In her book The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap, University of California Irvine law professor Mehrsa Beradaran observes that for neoliberals, laws prohibiting discrimination are as unjustified as laws requiring discrimination.

Neoliberals frame housing as a commodity that should be governed by the laws of the marketplace, rather than a basic human necessity. Within this paradigm of market fundamentalism, it is difficult to find any justification for a productive role for the public sector in housing policy.

There is no true “public option” in the development of housing in the United States, and definitely none that is available and accessible to most Americans. Each public sector entity works within its own bureaucratic silo with limited accountability. This “unhousing” of the public sector under the neoliberal model has made it easy to villainize the public sector. It has opened the door for criticisms such as that “Big Government” taxes some people to subsidize others, passes regulations to address social issues that make housing an unprofitable commodity, and is an inefficient gatekeeper for private property rights through land-use zoning. Private builders perpetually blame government bureaucrats and politicians for the housing crisis, often while shirking their own social responsibilities.

And yet the abstract distinction between public and private dollars failed to hold up when publicly backed companies, known as government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs), especially Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, bought the private mortgages of millions of Americans during the Great Recession. These enterprises are currently considering one of the largest public offerings in history to undo these governmental bailouts, and are being advised in this process by Wall Street giants JPMorgan Chase and Morgan Stanley.

Housing has been transformed into an investment vehicle via speculative financial products that connect the mortgage market to the stock market. These products often have government backing. Speculative financial products are tradable goods where the focus is on the product’s price fluctuation on the market, rather than interest accumulation or profit-sharing. Over the past decade, there has been a mushrooming of speculative real estate equity deals in the U.S. in which housing is valued primarily as a place to store capital and generate higher returns than investments in jobs typically do. To attract investors to these deals, builders gravitate toward more profitable (and therefore more expensive) products. As the consolidation of the building and construction industry has made it less competitive, it has gotten less likely that any production-side savings flow to the end-user.

Compounding the problems of a profit-driven housing finance system is the issue of systemic racism, which the real estate industry has never addressed meaningfully. Many exploitative practices in the industry existed prior to redlining and continued even after housing discrimination was banned. The failed U.S. housing system has allowed wealth inequalities, social unrest, racial disparities, and rampant homelessness to fester in America’s cities. Public frustration with this status quo is part of what is boiling over with the Black Lives Matter movement.

It is therefore time to reexamine this neoliberal model and the artificial walls it has set up between the public and private sectors.

In the visionary words of the nation’s pioneering “houser,” Catherine Bauer:

Irritating though it may be to purists of both the right and the left, the national ability to disregard abstract dogma (for which Americans have little gift in any case) in favor of desirable concrete goals is a potential source of flexibility and strength to the United States in facing an uncertain future. To achieve homes and communities worthy of its knowledge and resources and traditional ideals, the political and philosophical dividing line must not be on the abstract issue of “public versus private”: instead it must be the line that puts the rigid, the cynical, the fearful, and the nonproductive on one side, and all truly productive, democratic, and humanly hopeful interests on the other.

A new model of housing provision could harness the collective capacity for concerted social action put into motion by emerging social movements. If we break down these artificial walls, we could marshal the best qualities of both the public and private sectors to provide affordable and accessible housing for all Americans.

A New Deal-Type Housing Agency

I suggest that we anchor a new model of housing provision with a federal agency that would be responsible for the development, finance, construction, sale/lease, and operation of housing for the working class. This Housing Development and Finance Agency would be given the types of tools and levels of resources that were given to the Public Works Administration during the New Deal. Similar agencies at the state level may also be deployed.

The new agency would have three functions in the field of housing: finance, development, and regulatory oversight.

- Finance: Coordinate and leverage different funding sources (e.g. bonds, tax credits, private equity, institutional funding, etc.) to fund its own and other projects. This would include providing capital for housing products that are government-backed, through GSEs, rather than going down a path of complete privatization of these enterprises.

- Development: Acquire property, build, own, and sell projects, with a triple bottom line that would consider financial returns, social benefits (e.g., good quality local jobs, very low-income inclusion, etc.), and environmental sustainability (e.g., access to transit, renewable energy, etc.). The goal of the agency would be to provide housing affordability for a wide range of incomes and all tenure types (rental, ownership), including transitions between them as households change over time.

- Regulatory oversight: Singular agency responsible for all mortgage-based financial products, fair housing laws, community reinvestment, and consumer and tenant protections, as well as housing-related tax expenditures (including tax credits). This would include oversight of the GSEs, for which there is currently no central regulatory authority.

This model has worked successfully in Singapore, and has inspired programs such as the “ALOHA Homes” program in Hawaii, in which the public agency Hawaii Housing Finance and Development Corporation partners with private builders to construct and sell unsubsidized affordable housing near transit with 99-year leases. Singapore’s Housing and Development Board is not only the nation’s largest developer, but also manages a stock of a million flats, provides mortgages for its units, sustains a secondary housing market, and facilitates savings investments into the housing stock.

A Housing Development and Finance Agency could be structured to be a one-stop shop offering the following:

- Emergency deployment of federal resources based on humanitarian need.

- Scalable supply of housing and housing lending product types and quantities that match consumer demand, going beyond the limited types that are currently considered financeable by the private sector.

- Comprehensive public input on the size and scale of development.

- Increased competition through a public choice, thereby unclogging the oligopoly that large developers have over some metro markets.

- More choices for residents in terms of tenure, for example, in duration of contract and lease/purchase options.

- A flexible rent structure that allows for incomes to rise and fall without prompting undue hardship, or fear of eviction.

- Freedom for residents to move between agency projects.

- An easier journey for potential homeowners they could purchase a housing unit that came with a financing package tailored to meet the buyer’s qualifications.

- Reduced moral hazard of selling a family a unit it cannot afford, since the mortgage is backed by the same agency.

What It Would Take

A New Deal–type public agency working on housing would need three key elements to be successful: public support, broad clientele, and partnerships with both public and private sector actors.

The first element is public support. There will be substantial public support needed at launch, due to the resources it takes to get projects built at a scale that is large enough to have an impact, pool risk, and generate efficiencies. This may be initially challenging with government debt ballooning during the pandemic recession. However, as time goes by, the housing that has been developed will start generating returns, such that the public support can be weaned off to the extent necessary. It is possible that states may create their own agencies to direct resources that they can control. Since this proposal blends the regulator and regulated aspects of housing production, it needs effective and independent oversight and public accountability. Research shows that a more centralized housing agency, such as that in California, is more innovative.

The second element is a broad base of clientele, one that includes low-income and middle-income households, young and old, families and singles, buyers and renters. For this model to be sustainable, the agency’s projects must be inclusive of a wide range of incomes. In the Viennese model, housing is widely accessible and available. Unlike for public housing in the U.S., income eligibility includes the middle-class, and families can stay in their apartments even as their incomes go up. Social and economic integration creates opportunities for upward mobility and may be used to cross-subsidize the housing. Housing is not just a place to seek shelter, but a place to build community. To attract a diverse range of workers, the quality of the architecture, interior design, accessibility features, and associated amenities must be superior and adaptive to contemporary tastes. The agency would need to have a diverse portfolio of different housing types, tenures, and targeted regional markets in order to spread the risk and to prevent stereotypes associated with past public housing projects.

The third element is a partnership with local public agencies and with for-profit and nonprofit private developers and owners. There are many agencies at every level of government that already deal with housing or housing finance, and some combination of consolidation and collaboration will be required.

Many public agencies, such as school districts, own considerable amounts of land that could be made available for housing, but they do not have the expertise to build it themselves. Publicly owned, privately run corporations could manage the projects, similar to how port redevelopment worked in Copenhagen, Denmark. (However, the private sector construction and maintenance workers must have collective bargaining representation so that they can be empowered at the workplace. Growth in union membership is critical to reversing the rise in income inequality and broadly sharing the benefits of urban development.)

In the Viennese model of social housing, there is a vibrant partnership between Vienna’s public and private sectors. Private developers get low-interest rate loans if they build housing at restricted rents and reinvest some of their profits back into housing. Developers also compete on available construction sites as well as project financing, based on the quality of design, housing affordability, and amenities.

Small-scale housing projects could be acquired or developed in partnership with small local developers or community development corporations for a fixed developer fee. This is similar in concept to low-income housing tax-credit projects, except that the projects are funded and owned by the federal agency or community-based nonprofits rather than by investors. The agency may turn over a project to a nonprofit cooperative or local housing authority to manage and operate with the active participation of tenants. For example, a legislative proposal in California (SB 1703) would create a unique legal framework for qualified organizations to purchase properties that are distressed due to the pandemic recession by giving them the right of first offer. They could then convert them into affordable housing.

The housing question is no longer simply about housing; it is about gaining access to financial assets. As Columbia University professor Saskia Sassen describes in her book Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy, the loss of homes in a financial crisis is not merely about housing becoming a bit more expensive, but about a loss of power—people systematically starved of opportunity. The socioeconomic transformation envisioned by the Black Lives Matter movement, and the economic recovery programs from COVID-19 will fundamentally alter the nature of the roles and responsibilities of the individual vis-a-vis the state. “The housing question has returned with a vengeance,” writes Sassen. “One major challenge is how can we develop new housing models for our current period.”

The creation of a New Deal–type housing agency is critical in order to address the housing crisis looming over millions of Americans. Housing in the United States is dependent on both public and private dollars, and in order for it to work, the policy paradigm must shift so that the public and private sectors work together. A house with a divided foundation cannot stand.

There is such an agency called HUD. It needs to be empowered and given some new tools to accomplish what you want