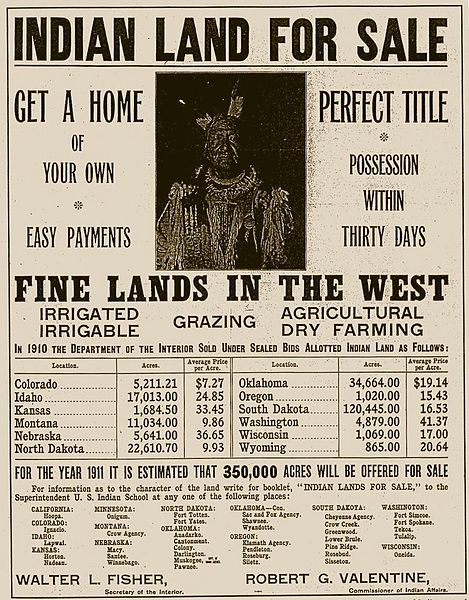

United States Department of the Interior advertisement offering ‘Indian Land for Sale’. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Many of the economic challenges facing our nation—the racial wealth gap, the homeownership divide, inequities in credit access—have their origins in discriminatory housing and economic policies implemented from the colonial period through present times. But there is also a centuries-long ethos that many Americans have internalized: that their accomplishments were largely the result of a hard work ethic and a determined grit, and that others who did not achieve similar success just did not work hard enough, got themselves into trouble, or were not smart about the choices they made in life.

The reality is that white Americans have always benefited from supportive systems that propped them up, making the American Dream more attainable, while people of color have been deliberately excluded from these same opportunities. This disparity is probably best illustrated in the way our country has provided, or not provided, access to the single most important determinant of wealth for the majority of people in the U.S.—home and land ownership.

To better understand this dynamic, let’s start with a history lesson.

Long Before Redlining

Historical “housing” policies from the initial colonization of what is now called the United States formulated the basis for current homeownership and racial wealth gaps, and our dual and bifurcated credit market.

When Great Britain established colonies, it offered what were known as headrights to settlers. The headrights system, credited for the quick and broad expansion of the thirteen British colonies, provided heads of households 50 acres of land (or more) for each person in the household, including indentured servants and slaves. But the land granted these settlers was not just free for the taking. It was land that was primarily seized from indigenous tribes. Militias were employed both to commandeer lands and provide protection to settlers and assist in infrastructure development and building projects.

The provision of lands and assistance provided by troops came at a not-small cost supported by government and corporations like the Virginia Company and Plymouth Company. It was this government supported resource that made it possible for early settlers to obtain land and pass down wealth for their families.

The headrights system morphed into the Land Grant and Homestead Grant programs, which were based on similar principles. Land grants were given to veterans of the Revolutionary War as payment and compensation for their service. Ironically, enslaved Black people who requested their freedom, given the premise of the Revolutionary War–freedom from tyranny–were denied, and slavery would continue for another 82 years. New European immigrants who became citizens, as well as those who were already living in the United States, including people who were formerly indentured servants, were able to take advantage of these government supported programs. These programs, which helped fuel the policy of Manifest Destiny, came at great costs for indigenous people, who lost more and more of their lands, lives, culture, and possessions as white people moved west.

The programs were a great benefit to settlers and their descendants. The U.S. government not only supported people by gifting them land, but the country provided military support funded by taxpayer dollars to the families pioneering central and west America. Armies were deployed throughout areas that were being granted freely to white settlers to help commandeer lands, remove native nations, and in some cases build infrastructure.

U.S. citizens received 1.6 million homestead grants, and through headrights, land, and homestead grants combined, hundreds of millions of acres were redistributed, amounting to a phenomenal transference of wealth. These programs almost exclusively benefited white people. For a short period post-Reconstruction, the federal government sought to make the homestead program fair and accessible to people of color, particularly those formerly enslaved who had received no compensation for their years of forced servitude. Some Union Army generals promised African Americans 40 acres and a mule as a form of reparations for slavery, but this never materialized. Instead, Congress awarded some former slave owners $300 for each slave lost as a result of the end of the institution of slavery.

In 1872, Congress amended the Homestead Act to make it illegal to make a distinction “on account of race or color” in the issuance of homesteads. But, much like the Civil Rights Act of 1866, after Reconstruction, efforts to enforce anti-discrimination laws were null and void. Jim Crow laws were passed throughout the nation in an attempt to establish de facto slavery and establish opportunities expressly for whites while blocking people of color from gaining access to the benefits of society.

After the onset of the Great Depression, the government largely supported homeownership via two federal agencies—the Homeowners Loan Corporation (HOLC) and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). The HOLC was developed to save homeowners from foreclosure and provide a new system that would help them sustain homeownership. It was the HOLC that developed the fully amortizing, long-term, fixed-rate mortgage. The agency also institutionalized redlining and the association between race and risk that still systemically affects borrowers today.

Housing Discrimination—Mapped and Institutionalized

The HOLC developed Residential Security Surveys and Maps to identify areas deemed safe for government-backed lending. The surveys and maps grouped neighborhoods into one of four categories: Grade A – green (best), Grade B – blue (still desirable), Grade C – yellow (definitely declining), and Grade D – red (hazardous).

The presence of African Americans in a neighborhood, no matter how small, generally necessitated a red or hazardous grade. While I have not read every Residential Security Survey, I have reviewed many, and have yet to come across any area that had African American residents that was not coded as red (D-grade) or hazardous.

The survey form had a special place for real estate professionals completing the survey to indicate the percentage of “Negro” population—no other specific racial or ethnic group is treated in this fashion. The HOLC did not create redlining, but it institutionalized the practice and provided the infrastructure for it, a system of maps for 200 cities across the country redlining communities with African Americans and other people of color and a formula for determining (if no map existed for a community) which areas should be deemed “hazardous”.

Municipalities funneled taxpayer dollars to green and blue areas and away from redlined areas. It did not matter that residents in redlined communities were paying taxes. The financial support they contributed to their local and state economies were funneled to areas deemed worthy of investment and those areas were not communities of color. An analysis done by The Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago found that the impact of the HOLC’s redlining maps still effect communities today, revealing that C and D graded areas experienced significant increases in African American residents from the 1930s onward as housing policies and practices steered them to these neighborhoods, dramatically increasing residential segregation. They also found “long-run decline in home ownership, house values, rents, and credit scores.”

The FHA program, which provided federally-backed insurance for mortgages, extensively broadened homeownership opportunities for white Americans. The U.S. homeownership rate had never topped 50 percent prior to the advent of the FHA program, but grew from a low of 43.6 percent in the aftermath of the Great Depression in 1940 to over 60 percent by 1955. But this program, which made homeownership and wealth attainment possible for millions of people, utilized the HOLC’s redlining maps, making the program largely unavailable to people of color. The FHA underwriting manual not only promoted residential segregation but described people of color as “incompatible racial and social groups” and “inharmonious racial groups”. The manual, likely contributed to by Homer Hoyt, FHA’s first Chief Housing Economist, encouraged the use of restrictive covenants by giving preferential treatment to the communities that adopted them.

The government backed $120 billion in mortgages from 1934 to 1962, but the race-based policies of the FHA meant that, for the first 30 years of the program, fewer than 2 percent of FHA mortgages went to people of color. At a time when white Americans were amassing wealth to fund their children’s education, seed inheritances, and start businesses, people of color were denied this unique benefit and foreclosed from the ability to build wealth. Had the government not discriminated in the HOLC and FHA programs, and demanded that those operating these federal programs abide by the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the 14th Amendment, people of color, and African Americans in particular, would have been able to make normal strides in gaining wealth and access to the opportunities families need to thrive.

Instead, the government’s policies expanded the credit access gap, inculcating the association of race and risk into our financial and housing systems. More and more fringe and subprime lenders popped up, stepping in to fill the gap left by the mainstream financial market and the federal government.

Which leads us to where we are today.

Thank you for an excellent article. The clarity and historic foundation provided refute any argument presented for the lack of intentional and institutionalized racism. You insights also provide support for the argument of reparations.

I recall back in the 60’s when my hardworking African American parents tried to get a bank loan to buy a house. Their dream to buy a small modest home was denied. However, the owners agreed to “take back” a private mortgage and allowed my parents to pay off the loan. The price was a bit inflated and had a high interest, but they eventually paid it off. It still saddens me……….

Your family’s story is similar to mine. My parents had to get a subprime loan at over 13% to purchase their first home. Our neighborhood was redlined. Many of our neighbors suffered the same fate. It’s why we must keep fair housing laws strong. If you have a chance, please visit our campaign to do just that – http://www.DefendCivilRights.org

– Lisa Rice