Several years ago, I attended a workshop about how to approach funders at a national community development conference. The workshop included a few mock “first conversations” with funders, who then gave feedback on how the prospective grantees presented themselves. My notes are long gone, but I remember two takeaways from what the funders said: 1. If someone offers you a drink of water, accept it. 2. If you’re meeting with a bank, be prepared to explain in some detail how what you do fulfills their Community Reinvestment Act obligations, or they won’t be able to help you.

The Community Reinvestment Act, or CRA, is so much a part of the landscape of community development that when it is not under threat we almost take its pivotal role for granted. Activists fighting against bank redlining got the landmark legislation passed in 1977, and its objective was to ensure that banks invested in the places where they took deposits, instead of starving certain areas of credit, damaging both individual prospects and entire markets. Under CRA, depository banks are evaluated every three years within assessment areas based on their market footprint. The evaluations look at their retail services (branches, appropriate products), lending to low- and moderate-income (LMI) individuals and businesses, and their community development investments, which include things like equity investments in affordable housing development and support for organizations providing credit, development, and services in LMI communities.

Community groups get to weigh in with each exam about how well banks are serving the particular credit needs of their particular communities, and a poor rating could prevent banks from getting approved for a merger or acquisition or other growth activities that require regulator approval. Ratings are also public, and so there is a PR incentive to have a good one. Although there has been longstanding concern about whether CRA exams are too easy to pass, CRA has nonetheless had a measurable effect on financial institution investment in LMI communities.

Many things that CRA tests for benefit communities directly—more branches, more retail services, more mortgages. But given the long-term effects of redlining and disinvestment in many of these neighborhoods, there’s also a need for infrastructure to translate some of these investments into positive change on the ground. Living Cities, a consortium of community development funders and financial institutions, calls this need “capital absorption capacity,” which it defines as “the ability to make effective use of different forms of capital to provide needed goods and services to underserved communities.” In the case of CRA, there’s a need for organizations that specialize, for example, in developing affordable housing, lending to and supporting small businesses, doing homeownership counseling with first-time homebuyers, and helping households and communities of color overcome the legacy of being offered only second-class, exploitative financial products.

That need is fulfilled by the community development world. Community development corporations, community development financial institutions, and the national intermediaries that work with them provide the infrastructure for CRA-motivated investments to land. They have expertise in doing this kind of development and lending, have the ability to leverage other kinds of funding and subsidies, and have developed trusted relationships with residents who are potential borrowers and beneficiaries.

Given how these functions align, it’s no surprise that CRA-regulated institutions are a major presence within the community development world. All told, the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC) estimates that just the 25 largest banks alone generate about $35.6 billion per year in community development loans, equity investments, and grants. CRA is a “fundamental pillar of the multi-billion dollar community development sector,” says Noel Poyo, executive director of the National Association of Latino Community Asset Builders, in recent testimony to Congress critical of proposed reforms to CRA regulations.

And yet, we don’t often talk about how much community development as currently practiced depends on this financing and funding from banks. (This may in part be because of some discomfort with working with organizations whose corporate entities are often in the news for causing the kinds of harm community development is trying to fix.)

Given the major CRA-related changes that are being proposed by the OCC and FDIC, Shelterforce spoke with a range of community development organizations, from national to local, and big to small, to get a sense of just how much they rely on CRA-motivated investments to do their work. Even from our small survey, some pretty clear trends emerged.

Essential Financing

First, the financing of community development projects—whether couple-unit rehabs and playgrounds or massive multifamily affordable housing projects—is extremely reliant on CRA motivations. Nearly every community development project has some participation from at least one CRA-regulated bank, if not more—including equity investments via Low-Income Housing Tax Credits and New Markets Tax Credits, construction loans, gap financing, or special impact investment funds.

Since the market crash of 2008, the vast majority of Low-Income Housing Tax Credits investors have been banks. Priscilla Almodovar, CEO of Enterprise Community Partners and the former head of community development banking for JPMorganChase, notes that this is because CRA assessments have so far included a separate investment test in addition to lending. The investment test required banks to make equity investments. “The most efficient, easiest, [most] impactful ways to meet the investment test are LIHTC [Low-Income Housing Tax Credit] and NMTC [New Markets Tax Credit],” explains Almodovar. The community development intermediaries Enterprise and Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) often serve as go-betweens connecting financial institutions looking to fulfill this part of their CRA mandate with community development groups in their assessment areas who have been awarded tax credits and need investors.

But a CRA-motivated investment doesn’t have to involve a major LIHTC project with a national bank to be critical to a community development project. “CRA has been essential to our work for decades now,” says Tom Collishaw, president/CEO of Self-Help Enterprises, which works in eight counties in the San Joaquin Valley of California. “It’s probably the single biggest reason why regional and small banks are interested in working with us. We’ve used them to finance small subdivision developments, small gap financing. Those small gaps they can come in and fill are crucial.”

The Urban Land Conservancy (ULC), an organization that functions similarly to a land trust and has developed large quantities of affordable housing in Denver, Colorado, has an acquisition fund that allows it to move quickly to purchase strategic parcels of land where, for example, a transit stop is planned and prices are likely to rise. This kind of flexibility is something others in the field often dream of, and it was also enabled by CRA. Half of ULC’s fund was seeded by a $25 million local bank investment that was explicitly CRA-motivated. As flexible as the fund is, those dollars can’t be invested in anything that’s not CRA-eligible, says ULC president Aaron Miripol. ULC’s individual projects also involve CRA investment in tax credits.

“CRA funding is often the first-in dollars,” says Marie Morse of HomesteadCS, a housing counseling agency based in Lafayette, Indiana, “meaning it drives rehabilitations, loans, and developments that then spur broader market interest.”

How do the organizations getting this kind of financing know that the banks are being motivated by CRA? Often because the banks say so. The extent of the motivation often becomes clear when a project outside a given bank’s CRA assessment area comes up. “Every bigger bank we meet with, their CRA needs are always part of the discussion,” says Jessica Andors, executive director of Lawrence CommunityWorks Inc. in Lawrence, Massachusetts. “There’s been times we’ve approached one, and they say ‘Sounds like a great project but we don’t have a CRA need in your area right now.’”

“Banks have been the most aggressive equity sources for us in our tax credit process,” agrees Collishaw. “That is entirely driven by their CRA footprints. We’ve had investors who we’ve worked with multiple times, and we’ll send a deal to them, and they’ll say ‘It’s not in our footprint so we’re not interested.’”

LISC, a national intermediary that disburses approximately $1 billion in community development investments each year through national investment funds and 35 regional affiliates, matches bank assessment areas with the footprint of the projects it’s financing, says CEO Maurice Jones. “By far our largest investors in that work are CRA-motivated investors,” he says. “We could not do our work to anything like the extent we are doing now, but for CRA. It is undeniable.”

This doesn’t mean other motivations never enter the picture. Some community development organizations say that especially for smaller community banks, CRA can be a motivation to get them to the table the first time, and then they recognize the deals as good ones. “It is almost always what brings them to the table,” says Morse. “They stay because they learn it is good business.”

“We’ve had some come to us reluctantly and then we do a deal and they go, ‘Wow this is a good deal, bring these all to us,’” says Collishaw. “They end up understanding this is a solid balance sheet.” Of course, he adds there are others that “don’t want to do deals, they just want to send you a check for $500 once a year” to check off a CRA-compliance box.

Nonetheless, nearly every practitioner I spoke with believed that CRA was the primary driving force behind the investments they were getting, and that sense is backed up by broad data. It has long been pointed out, for example, that rural areas, which tend to be short on bank branches and therefore fall outside of financial institutions’ CRA assessment areas, also struggle to get bank investment. This disparity is not a good thing, but it does highlight that CRA is actively affecting banks’ decision-making processes. NCRC has also argued in two studies, published in 2005 and 2009, that large credit unions, which are not covered by CRA, consistently perform worse than banks on a range of fair-lending measures. These reports did not include levels of community development investment, but among the organizations I spoke with, credit unions were far less common investors than banks. Other types of non-bank lenders not covered by CRA were almost entirely absent, aside from Quicken Loans’ direct investments in downtown Detroit, which have been controversial.

Outsourced Community Development Lending

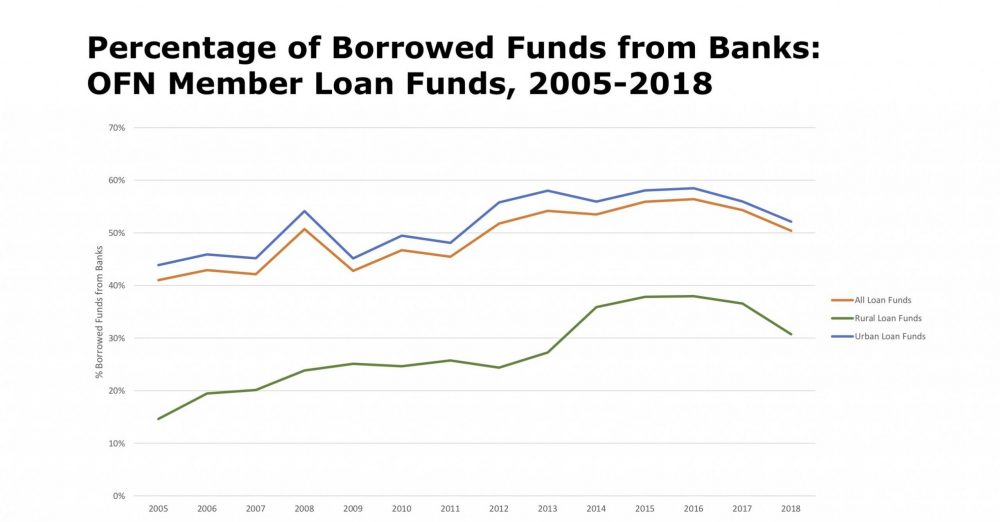

Lending to small businesses and development activity in LMI communities through community development financial institutions (CDFI) is another community development activity that relies heavily on CRA-motivated investments. CDFIs make loans to borrowers, and in locations, that are underserved by bank loans. Investments in CDFIs became CRA-eligible in the mid-1990s with the creation of the CDFI Fund at the U.S. Treasury. CDFI loan funds that are members of the Opportunity Finance Network currently receive about 50 percent of their lending capital from CRA-regulated financial institutions, down from a peak closer to 55 percent a couple of years ago.

Lending capital to CDFIs enables banks to achieve their own CRA-related lending goals—such as reaching small businesses—without having to adjust their own internal underwriting criteria or develop the kind of high-touch infrastructure that CDFIs employ to help their borrowers succeed. “A bank isn’t going to want to make a smaller loan,” explains Jennifer Vasiloff, external affairs officer for the Opportunity Finance Network. “It’s going to cost as much as a larger loan. If they give it to a CDFI, [the CDFI] will work with the smaller borrower or the small housing deal. The CDFI is on mission, the borrower gets the loan, the bank gets a return.”

“I’m an outsourced CRA lender for these banks,” says Jaycee Greene, community development lender for Gateway CDFI in St. Louis, Missouri, whose lending capital comes 100 percent from banks. “These loans wouldn’t be approved if the bank was doing it on their own.”

Operating Support—Small but Important

Banks are a critical player in financing community development deals whether they are large or small. But when it comes to grants, the way the funds are allocated looks different at different geographical scales. Banks do earn CRA credit for grants, according to the NCRC, even when they come through a separate foundation, as long as the activities being funded are CRA-eligible.

For local organizations, bank grants are usually a small portion of their operating funds—5 to 15 percent—and are generally focused on homeownership counseling, financial counseling, or other direct services. But while the amount is small, these grants are still valuable, for three reasons: they often fund things that are hard to fund (i.e. ongoing services rather than something with a ribbon cutting or a pilot of a new approach), they are often fairly flexible funds, and many organizations have found they tend to be more consistent over time.

Bank grants, for example, make up just 8 percent of the annual operating budget of Lawrence CommunityWorks (LCW). But, says LCW’s director, Andors, “We rely on those banks to fund our asset-building programs. … They are not the core part of my budget, but they are the most consistent funders.” Andors says relationships with bank funders can easily last 10 to 15 years, whereas “if I can get 6 years out of a foundation I’m ecstatic.”

“It’s tiny but important,” says Collishaw, “especially in some areas where it’s hard to attract funding consistently to do the work—financial education and counseling, resident services, literacy and after-school programs. Foundations want to know how you’re going to sustain the program after you’re done [with their grant].”

For community development organizations with a larger geographical footprint, bank grant relationships vary more. Members of the National Alliance of Community Economic Development Associations (NACEDA) are regional or state-level associations of local community development groups. When they were surveyed in 2014, the percent of their operating budgets that came from bank grants ranged from 0 to 70 percent, with half at 16 percent or below, and more than one-third over 30 percent. For NACEDA itself approximately two-thirds of its budget comes from bank funding. Most, though not all, agreed that bank funders were unusually consistent compared to other funding sources. (Shelterforce also currently receives approximately 15 percent of its budget from bank grants.)

“The philanthropic sides of the banks have been one of the most important sources of funds for us for operating capital,” says Jones of LISC. “No question in my mind that if we lose that, that our capacity, and the capacity of the field would be irreparably damaged.”

“Banks have historically been our No. 1 philanthropic donors, not just the largest, but the most reliable, the most aligned,” says Enterprise’s Almodovar. “They’ve been with us for 25 to 30 years.”

Additionally, large financial institutions have put together over the years a number of targeted competitive grant programs such as JPMorganChase’s ProNeighborhoods or the recently announced Wells Fargo and Enterprise Community Partners Housing Affordability Breakthrough Challenge, which deliver shorter-term but larger grants to a few select organizations.

“The CRA activities of banks are so much more than just grants,” says Marietta Rodriguez, president and CEO of NeighborWorks, whose network includes Self-Help Enterprises, Lawrence CommunityWorks, and Nuestra CDC. “CRA is about lending to people, investing in their communities, and providing access to services and products, as well as serving in leadership and partnership roles in and with organizations. Our organizations engage with banks in all of these ways.”

A Relationship in Danger?

While these funding and financing relationships are now longstanding and mature, they still rest on a foundation of CRA regulations whose future is uncertain. The OCC and FDIC (but not the Federal Reserve, which also implements CRA for banks it regulates) are proposing major changes to how banks are assessed on their CRA commitments that have the potential to upend community development infrastructure.

The primary change involves switching to a “one ratio” measure. What is currently a set of context-dependent qualitative and quantitative tests would be reduced to one fraction—total CRA-eligible dollars over total deposits. This ratio would be calculated for a bank’s whole business and for each of its assessment areas—but only 50 percent of assessment areas would have to hit the minimum benchmark for the bank as a whole to pass, a clear invitation to return to redlining. In addition, some investments in infrastructure and sports stadiums in low- and moderate-income communities would now qualify for CRA credit without any requirement that they primarily benefit low- and moderate-income residents. And the role of community voices in the assessment process would be practically gone. (Read more details on what is proposed at Treasure CRA.)

Every community development organization representative I spoke with is concerned that the one-ratio measure would incentivize banks to make fewer, larger CRA-eligible investments. After all, fewer larger investments are simpler. Angie Liou, of Asian Community Development Corporationin Boston, which has relied on banks’ CRA motivation to provide mortgages for an affordable condo project the group developed, is worried. “If the emphasis is tilted toward the [total] amount, that will work against smaller mortgages,” she says. “If you shift the rules, banks are going to look for what is the way that takes the least amount of effort. If they can get there by doing one big loan instead of 50 little ones, why wouldn’t they?”

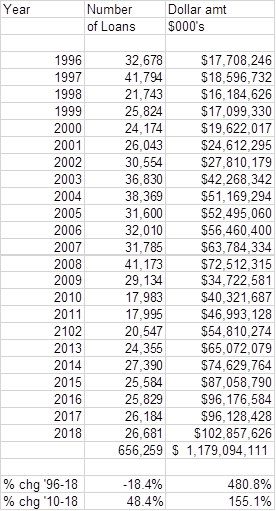

The size of community development investments has already been going up while the number of them have been going down, according to data from NCRC. From 1996 to 2018, the number of community development loans annually has decreased 18.4 percent, even while the total dollars have increased 480.8 percent. The one-ratio measure would likely accelerate this process substantially. And in combination with infrastructure and stadium projects being newly CRA-eligible, it may not only steer investments to larger organizations, but outside the community development world entirely.

Courtesy of NCRC

Even CDFI lending, which is in a sense already a larger investment outsourcing the ability to do many little investments, is still usually “for a big bank, a small transaction compared to a large affordable housing deal, or infrastructure,” says Vasiloff of the Opportunity Finance Network. “By changing the whole conversation to a numerical goal that banks have to work toward, you’re very much advantaging larger, easier transactions, and those are not always the ones that are most impactful.”

Removing the requirement that all assessment areas need to pass would also remove the incentive to figure out how to get capital into the places that need it the most. “Because we were forced to do things in assessment areas, I had to do things in smaller areas, places that were hard to find opportunities,” recalls Almodovar of her time at JPMorganChase. Without that motivation, capital may flow only to the easiest-to-invest-in places.

Even now, “when investments are made around the city, we often don’t see them,” says David Price of Nuestra CDC in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston. So he expects these changes would only make things more challenging: “I can easily see them having a good number for Boston or Eastern Mass, but not doing anything for us.”

Not Just Money

There’s another potential loss to making CRA assessments a matter of a single, simple number. As of now, large banks have put significant staff resources into CRA compliance, building talented teams who have close relationships with their community development partners and direct access to the C-suite at their institution. Many of those people also volunteer on CDFI lending committees and boards, and teach portions of homebuyer education classes (something that it seems will no longer separately count toward CRA assessments under the new rules). These relationships are two-way streets, with community development bankers also turning to their community development partners for feedback on how best to meet community needs. If CRA compliance loses its qualitative and context-dependent components, will that staffing be lost as well? Many fear that, as Price of Nuestra CDC says, “these big institutions’ commitments to these teams might weaken and they might disappear.”

The CRA qualitative tests “forced banks to think thoughtfully,” says Almodovar. “Because of them, the large banks had community development groups with subject matter experts. It’s what gave us the clout internally to get the banks to lean in to develop certain products, to increase the underwriting box. I think banks do want to do the right thing, but [the one ratio] takes away the incentive for those [community development] groups to have standing internally.”

Losing these teams would be a major setback even if the changes to the regulations were temporary.

Reform Needed—But This Isn’t It

Few people in the community development field think that CRA is perfect as is. It hasn’t shifted to represent online banking customer bases, or new kinds of financial institutions. It leaves out areas that are already suffering from being underbanked. Many advocates consider CRA exam grades inflated, with very few institutions failing despite community concerns about their lending practices and the continued closure of bank branches. Some positive steps to address these problems are even included in the current OCC and FDIC proposal.

Unfortunately, however, those positive changes are overshadowed by the likely negative effects on communities and on the community organizations that help banks’ capital get to them.

[Correction: This story originally stated that HomesteadCS was a NeighborWorks network member. Though its counselors are certified by NeighborWorks, it is not a NeighborWorks organization.]

Great article.

If any North Carolina folks want to support our petition to defend the CRA, please sign on at Reinvestment Partners’ change.org site.

https://www.change.org/DefendTheCRA