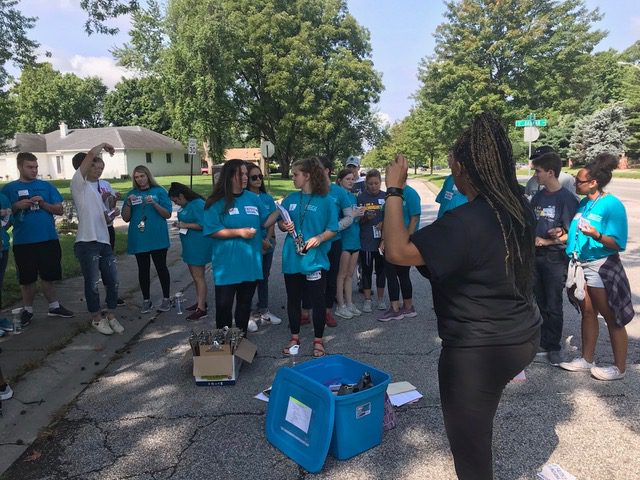

Photo courtesy of Faith in Indiana

In 2016, an Indianapolis-based faith organization launched a successful campaign to bring more funding to the mass transit system in Marion County. Shelterforce’s Miriam Axel-Lute talks with Nicole Barnes of Faith in Indiana about why the organization focused on transit improvements, how they balanced the tension between expanding rail line service and improving bus service, and how race had to be at the forefront.

Miriam Axel-Lute: Why did IndyCAN (now Faith in Indiana) pick transit improvements as a goal?

Nicole Barnes is the director of voter engagement and operations at Faith in Indiana.

Nicole Barnes: Transit was something that we believe was imperative for the work that we do. It aligns with our mission, which is to empower and give diverse communities the opportunity to work together. We want to serve as a catalyst for the marginalized and for faith communities so they can act together for racial and economic equity. Transit absolutely fit in racial and economic equity. When we started digging into the research, we saw how lack of transportation contributed greatly to poverty.

We had this opportunity to get transit on the ballot in 2016. Our leaders and our people [agreed that] this is something that will not just improve the city economically, but will also improve our communities from a racial standpoint [and] from an economic development standpoint. That campaign beautifully embodied our mission, which is to get people from all sides to work together toward something good.

We called this campaign “Ticket to Opportunity.” Even in our choice of what we called it, it [was clear it] wasn’t just about transit, but transit as an opportunity for people to get out of the circumstances that they were in. Traditionally, our organization is centered around leadership by the traditionally excluded—[the formerly incarcerated], Black and Brown [folks], immigrants—because those are the groups that are most impacted by a lot of the things that we see.

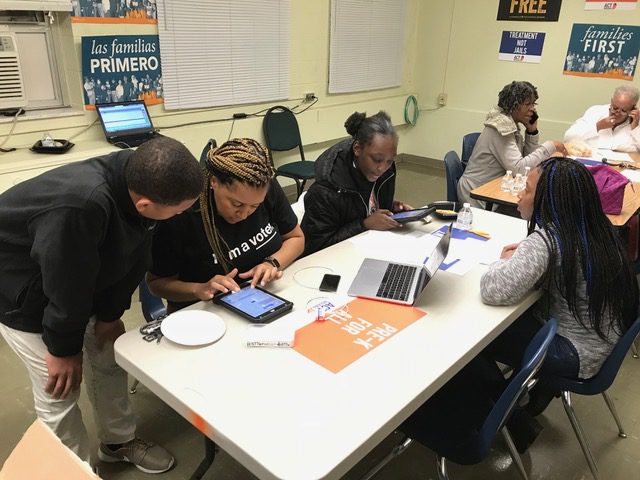

Photo courtesy of Faith in Indiana

We knew that “Ticket to Opportunity” was bigger than adding more buses, more rapid transit. The average commute for people was 90 minutes or [more]. Only about 13 percent of people could get to work in under 90 minutes on the bus. And then in neighborhoods that we worked in, we had a lot of service workers, a lot of retail workers, and the bus schedule just did not align with their work schedules. Think of Walmarts that are open 24 hours. Traditionally restaurants on the weekends close at 10, 11, 12 at night. Well, buses are done running. We had thousands of conversations with people about the impact of transportation, or the lack thereof, on their wellbeing.

And so, we knew this was a fight that we absolutely had to get into. We also knew that having allies was a requirement. Talking to bus riders and saying, “Hey, we want to add more buses, we want to have more frequent times,” of course they’re like, “Yes, yes, yes.” But we had to also make sure that we created a message and a narrative that also spoke to our allies who were like, “I don’t ride the bus. That doesn’t have anything to do with me.” How do we get people to see the value? Making it bigger than just about a bus, making it about the whole of the community.

We did a set of polls. Everybody wanted Indianapolis to (a) be more fair; and (b) be more competitive. This competitive piece really appealed to a lot of our non-bus riders. They’re like, “Of course we want to attract more businesses.” When Amazon was trying to figure out where they were going to go, and Indianapolis was in the conversation, part of that argument was, “Look, we have a rapid transit system that we’re developing so people can get to work.”

We worked with a collaborative. We had those who were responsible for the bike lanes at the table. We had AARP. And we worked our neighborhood housing organization. We worked with the Chamber [of Commerce]. The chamber did a lot of the blueprints, design and legal work, whereas we were the grassroots movement. We were the ones executing this vision.

We did some phone banking. We did some door knocking. We did it for 12 weeks, four and five days a week, and we just talked to people. We talked to people about, “What does transit mean to you? How will it impact your family?” The variety of stories that we heard regarding transit and how important this was was a big deal.

The platform was twofold. We understood that, with the construction of this [rail] transit line, and then also adding additional buses, there would be more jobs. We also had our Ticket Out of Jail [campaign] where we did a lot of work around money bail and diversion programs. How could we turn this into jobs for those who are coming off of probation or [have] recently been incarcerated? Everyone could find themselves in this platform.

You said that in 2016 you had an opportunity to get transit on the ballot. What was the particular opportunity?

Nicole Barnes: A ballot measure [to fund transit was] last [voted on] 10 years ago, and it didn’t pass. The city council was voting on the budget, and we knew that we would need funding for this platform. We were looking to introduce on a [citywide] ballot a [city] income tax increase of 25 cents for every $100, which would create new revenue of $54 to $56 million a year for this project.

We were asking people to say yes for transit. It was explicit that this income tax would contribute to the development of this transit system. At the same time, there was some federal funding that had also come down for another [rail] line. So, we felt like this was a prime opportunity because we knew that development for that [federally funded] line was starting, so we wanted to be able to have the two work at the same time.

In 2016, there was an advisory vote in the fall [where the] people [could] vote on an increase in the tax. It passed by 19 points. So then, in February, it went up to the [city] council. Because of the momentum from that advisory vote, we were able to get the council to vote yes as well.

They started development on some of the [rail] lines just a couple months ago. We’ve already seen some impact. They’ve started hiring minority mechanics [and] minority bus drivers. After the work that we’ve put in, actually being able to see it come to fruition is an amazing thing.

In terms of the specifics, such as making the bus routes align with people’s schedules or increasing the frequency, how much say did you have in how this money would be used? And how did you develop what you were asking for? Was that something you need to petition the transit agency for separately, or was that included in the vote?

Nicole Barnes: We talked at the beginning to IndyGo, [the transit agency] about communities that we know would be most benefited by this increase in scheduling, or by the expansion of this line. That all was decided on the front end.

There are two major streets that go across the city—East 38th Street runs east and west, and East Washington Street runs up and down. Those two lines that run through our city also run through some of our highest impacted, high-poverty, low-income areas. When the coalition came together, we knew that those two lines absolutely needed to be prioritized in regards to the expansion because we wanted to make sure that those neighborhoods had access.

In a lot of places, there seems to be something of a tension between expanding rail line and improving bus service. People see rail lines often serving more affluent people, or the amount of money going into a rail line seems disproportionate when you could get a good bang for your buck by really improving the bus systems that are serving poorer people. Was there any of that tension? How did you manage that balance?

Nicole Barnes: There was a little bit of opposition. And we didn’t necessarily ignore it. We knew that it was present, but we made sure that our message stayed on target, which was we want to make sure our city is fair. We want to make sure our city is competitive. We want to make sure people are able to get to work. We want to make sure that people have equal opportunity.

What I appreciate about IndyGo is there were some immediate things that were done right after that vote. So February 2017 was when the final vote was. Prior to [rail line] construction, last year in February, they rolled out enhanced bus services. They added up to 250 [additional] trips [per week] immediately, with many of them being on the weekends.

I appreciate how it was, “OK, the tax passed. We know the income is coming. But what is it that we can do in the interim to have some immediate improvement right now?” So we saw this increase in trips and scheduling almost immediately.

I believe this plan works in favoring both groups that you asked me about—rapid transit to some of our more middle-class areas and our high-poverty, low-employment areas. This plan was well balanced, and I credit IndyGo and the Chamber for their work on that.

Your executive director has said the organization decided it couldn’t ignore race and its impacts in your messaging on this campaign. How did you talk about it?

Nicole Barnes: The reality is, here in the city of Indianapolis, we could not deny race. Race had to be at the forefront, because the reality is, when you look at bus ridership, people of color use the bus the most. That’s the first fact. The second fact is, when I talked about our platform being twofold, we could not deny, in our county, the racial disparities of who is incarcerated. In 2016 at the time, here in Indianapolis, 1 in 4 African Americans were incarcerated as opposed to 1 in every 174 white people. You can’t deny that. The six ZIP codes here in Indianapolis that had the lowest employment rates are heavily concentrated with people who are Black and Brown. And those areas are also the places that rely heaviest on buses.

So race was something that we had decided had to be put in the forefront. As people of faith, if we value humanity, what the package looks like doesn’t matter. Shouldn’t we all be able to have the same opportunities and the same access? So that was a lot of our message.

So you acknowledged those disparities, and then said we shouldn’t have these, we should be giving everybody an opportunity?

Nicole Barnes: Yes. What resonated with people was putting families first. Regardless of what the family looks like, regardless of what your idea of family is, that resonated with a lot of people because when you talk about putting family first, people are like, “Oh, yes.” So how can we put policies and things in place where families can thrive and be the best that they can be?

I can remember one story where there was a middle-aged woman who lived right outside of downtown. It literally in a car is 20 minutes [away]. But because she had to be there at 9 a.m., and because of the way the bus operated, she got up at 4 in the morning to be at a bus stop by 5 a.m. so that she could catch the first bus by 5:30 a.m., and then transfer downtown, and then wait, and then take another bus to finally get her up north. Her commute was four hours. Four hours to get somewhere that I could get [to in] a car in 20 minutes.

In us connecting on this level of stories, we were able to find out where people’s values were. We have this African-American woman who is trying to get to work and needs to rely on a bus, and then we had a 70-year-old white male who was a retired health care exec. They’re having this conversation together, and she’s able to explain the impact of what transit means, he was able to connect with her and empathize with her, and that’s how they were able to work together, to fight together collectively.

Did you face any pushback?

Nicole Barnes: We had a little bit in our northern district, the Broad Ripple area. It’s an artsy area. Somebody got a billboard up saying vote no on transit. Their biggest complaint was parking. They were like “these bus stops are going to take away our already-limited parking.” But honestly, we didn’t stop to address it. We just -acknowledged that it was present when we all came together, but we would say, “Hey, this is what we’re fighting toward, so we can’t really get caught up on that.” And it worked out. It worked out tremendously.

Any lessons you’d want to suggest to somebody who wants to organize for better transit in their city?

Nicole Barnes: I think what really, really, really helped us have the sort of impact that we had was our collaboration with the community and with other groups, because we were able to touch so many different areas. Everybody stayed in their lanes and did what they knew they were able to do, what they were good at doing. So we knew, as the nonprofit grassroot organizing group, that grassroots organizing was our thing. And then you have to make sure that the people that are most directly impacted are the people that are at the center. We have to be led by them because they can speak to it from direct experience.

Thank you.

Comments