Little Tokyo. Photo by Seika, via flickr, CC BY 2.0

Over a year ago, Shelterforce invited Dean Matsubayashi, then the executive director of the Little Tokyo Service Center (LTSC) and me to write a piece about the anti-displacement organizing slogan popular in the Little Tokyo neighborhood of Los Angeles, “Welcome to Little Tokyo, please take off your shoes.”

A little before this initial invitation, Dean had been diagnosed with brain cancer. He passed on Sept. 4 of this year, survived by friends and family, including his wife, Kim, and children, Emma and Sei.

So instead of a collaborative article about displacement, race, class, culture, and organizing in gentrifying metropolitan areas, this piece has morphed into something more personal and mournful. The big issues are still here. But I also want to remember Dean, an incredible, generous leader and my good friend. I want to talk about how Dean saw the world, how he acted in it, and how “Welcome to Little Tokyo, please take off your shoes” typified his approach to life and his vision of justice. And about how, in these times, we need his ways of seeing, of being, and doing.

What Is Important to Know about Dean

Lots of people felt close to Dean. One important thing to know is that he was open and welcoming and had a way of becoming close friends with people almost instantly. But me, for most of the time that I worked at LTSC, I was super close to Dean. Literally.

Over the course of a decade and through three different internal office moves, Dean and I sat next to each other, essentially sharing a cubicle. Over this period, LTSC was growing quickly and we added space for new staff by cannibalizing common areas and rearranging our mismatched cubicles in new and creative ways. There was the time that Dean and I sat back to back so close that if both of us leaned back at the same time we would clonk noggins. There was the time that the arrangement of our two desks created an impassable labyrinth in the path to a fire exit door (a blatant code violation). Dean jokingly called our office arrangements a “nonprofit sweatshop.”

Another thing that is important to know about Dean—his sense of humor. Dean embodied the philosophy of “take the work seriously but don’t take yourself seriously.” His humor was often self-deprecating (like how he would joke about the coffee stains he would get on everything), sometimes goofy (he had lots of ideas for inventions, like a computer mouse designed to be operated by foot), and sometimes biting (like when pointing out an important truth). But, more often than not, Dean used humor as a bridge—to disarm people, to put them at ease, to draw people in, and make them feel included.

Another important thing to know about Dean is that he was a point guard. Basketball is huge in the Japanese American community. And, during his heyday, Dean was a star. You almost needed to be on the court with him to know how good he was—to see how he saw the game, to know how good he was at setting people up to succeed, to know how good he was at making his teammates better. And that was Dean in the rest of his life too. He got more satisfaction out of making an assist than in scoring points himself.

In meetings and other professional settings, Dean was especially good at managing the flow of the conversation without appearing that he was managing it. He was also good at setting colleagues up to look good, and always there to step up and step in if needed. After he transitioned to the executive director role, he told me that he had a lot less anxiety and a lot more comfort in the role once he figured out that his primary job as ED was to create space for other people to succeed. It was what he was good at. It was what he liked to do.

“Welcome to California, Now Go Home” vs. “Welcome to Little Tokyo, Please Take Off Your Shoes”

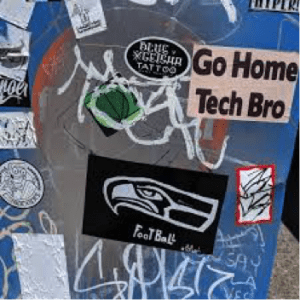

Photo by Josh Ishimatsu

In our fights against gentrification and displacement, we can have an angry (justifiably) and critical stance. On a recent trip to Seattle, I saw stickers and graffiti that said, “Go Home Tech Bro.”

This sticker reminded me of a bumper sticker I used to see when I was a kid during an earlier wave of population increase in California, and a corresponding wave of real estate price increases:

To my eye/ear, even as a kid, the “Welcome to California, Now Go Home” slogan had an ugly, racist, white-nativist undercurrent. The bumper sticker’s peak popularity was during the time in which California was transitioning from being a majority white state to one that was majority people of color. It is part of the overall social ecosystem that enabled Pete Wilson’s anti-immigrant Proposition 187, one of the forefathers to the “Build-the-Wall” strain of Trumpian populism. It’s why I am uncomfortable with the use of “Go Home” rhetoric, even when used in a progressive/activist context.

In contrast, the formulation “Welcome to Little Tokyo, please take off your shoes” coined by Christina Heatherton (when she was a student activist, volunteering and trouble-making in Little Tokyo) turns the “Go Home” rhetoric on its head while still being true to the underlying values of anti-gentrification and anti-displacement. In a piece that Dean and I wrote about LTSC’s role in the larger Sustainable Little Tokyo project, we said:

For LTSC, the challenge was to frame a vision of anti-displacement work that did not reify NIMBYism… How do we honor the past, prevent erasure, AND welcome the new in respectful ways… And, most of all, how can we do all this in ways that are equitable, sustainable, and empowering?

The answer, we said, is embodied in “Welcome to Little Tokyo, please take off your shoes.”

Many Japanese Americans (and many other AAPIs) have retained the cultural practice of taking off shoes at home or when entering someone else’s home. The slogan “Welcome to Little Tokyo; please take off your shoes” expresses the ethos that newcomers are welcome, but need to acknowledge and respect that they are entering a place with a pre-existing identity and normative culture. In this spirit, the Sustainable Little Tokyo planning process not only includes the participation of longstanding community stakeholders but also involves new residents who appreciate the role that the neighborhood has played (and continues to play) as a cultural hub and in supporting the community’s most vulnerable residents.

Sustained resistance to gentrification and displacement requires more than antagonism. It requires a community organized around an open, positive alternative vision that has both big ambitions and achievable, intermediary steps. Building a shared vision that has both lofty goals and concrete specificity requires organizing rooted in local knowledge and local relationships. Putting such a vision into practice requires persistence, creativity, and the ability to build and work within larger coalitions.

This ethos is quintessential Dean Matsubayashi, down to the fact that the central slogan, “Welcome to Little Tokyo, please take off your shoes,” was created by someone else. Dean was always enthusiastically lifting up other people’s ideas and doing his best to give credit where credit was due. This was part of his overall point guard orientation, and his generosity and openness of heart. It is the same generosity and openness of heart that is evident in the slogan itself.

A Continuing Vision of Justice

In our current moment, there are starkly different, competing visions of the world. They are building walls vs. building bridges; the presumption that it is better to be closed vs. the presumption that it is better to be open; the belief that success fundamentally comes from competition vs. the belief that success fundamentally comes from collaboration.

Dean was the best bridge builder that I have ever met. It was part of his M.O. It was how he was on a daily basis, and was fundamental to his larger vision of justice.

I miss him so much. And to those of us who knew him or even just admired him from a distance, the best way to honor his legacy is to continue our own work for social justice in ways that are grounded in Dean’s vision and the ways he worked—with openness, generosity, collaboration, irreverence (but still respectful underneath), and filled with humor and heart.

What a beautiful tribute. Thank you for sharing this.

josh: i read this and it made me tear up. i came by your office to give you a hug, but i think you were out of office today. take care, see you soon.

Thanks Josh. Loved this piece. You are right about Dean. . Take care.