A farmer on Windy Acres walking to tractor. Photo courtesy of Agrarian Trust

It’s estimated that we’ll see upwards of 400 million acres of farmland in the United States change hands over the next two decades as a generation of farmers and ranchers retire.

The elders in agriculture are doing their best to hold onto the tattered threads of skills and trades that have been passed down from generations of food producers and land stewards, knowledge that is slowly being lost due to obstacles that prevent fresh hands and eager minds from securing farmland. With the average age of farmers in the United States being 58, it has become imperative that a new generation of farmers step up to breathe new life into farms and landscapes that run the risk of being developed, gentrified, or sacrificed to the seemingly unstoppable blight of poison-ridden, heavily mechanized, single-crop-producing, sterilized land. To choose to farm today is a heroic task with few rewards, and yet somehow, within the pressure cooker of all of these forces, a new generation of land stewards is emerging.

These first-generation agrarians struggle with land access, affordability, and tenure. They are coming into farming often with limited resources, student loan debt, and are attempting to start a business on land that has been priced far outside of the economic viability of their proposed business’s profitability. The value of land—which ranges greatly across country as the same type farmland can sell for $300 to $400 per acre in one area, to $200,000-plus per acre in another—is based on an appraiser’s determination of highest and best use. The appraiser uses certain qualifiers to decide how suitable the land is for extraction or development and does not consider the natural value of a space or its ecological suitability for agriculture, unless top soil, aggregate, or timber are available to remove and sell for profit.

Farming elders often need to sell their farms based on the highest market value in order to cover mortgage debts and health care costs. Additionally, the bottomed-out price of agricultural products due to government subsidies, commodity farming, and a culture that does not value, choose, or pay for real food, generally finds farmers with little to no savings for retirement. Selling their farm to the highest bidder becomes the only means for financial stability in old age, and this means that the land is often acquired by Big Ag, development corporations, wealthy estate buyers, or foreign investment capital interests—entities that seek the land for extraction, development, or speculation.

How the Commons Works

At Agrarian Trust, we believe it’s time to chart a new way forward. We see the need to hold agricultural land in a community trust to ensure that elder farmers have the opportunity to pass on their craft while also preserving the ecological communities within a diversified, sustainable operation. These farms and agrarian properties not only serve as tools for reviving rural communities and bolstering small-town economies, but they also tie together the severely fragmented natural world. In the face of a changing climate, we have prioritized the importance of bringing people back in tune with the landscape knowing that this is the only holistic means for bringing empowerment, equity, and prosperity all while simultaneously allowing the Earth to tap into the replenishing homeostasis of regeneration. In the words of Malcolm X, “Land is the basis of all independence. Land is the basis of freedom, justice, and equality.”

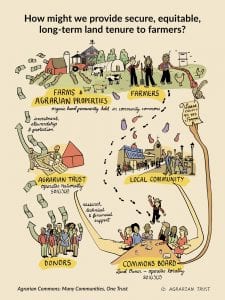

From its origins in 2013, the goals of Agrarian Trust have been based on a desire to provide land access to new agrarian communities and allow each individual group to establish its own system of management and leadership, influenced by identity of place. Agrarian Trust has steadily developed the Agrarian Commons model since 2016. The commons are multiple 501(c)(2) community-based landholding entities across the country that provide long-term equity leases of farmland and property to farmers and other agrarian enterprises. While the commons most closely resemble the community land trust structure, the focus on farms and the collaboration with multiple local farm-based CLTs that are aligned collectively is what makes the Agrarian Commons model unique. Here’s how it works:

- The local Agrarian Commons buys properties from farmers and farmland owners in their region through the support and fundraising efforts of the national Agrarian Trust.

- The local Agrarian Commons leases those farms to farmers using a long-term affordable and equity-building lease (99-years when state law allows).

- Each local Agrarian Commons is governed by farmers who hold leases, community stakeholders, and the Agrarian Trust.

Growth in the Agrarian Commons model occurs in a healthy natural state and everyone involved has a voice and a direct and personal relationship with the landscape and organization. Agrarian Commons develop five to six 501(c)(2) legal landholding entities at a time, with each starting with at least two farms and growing to not more than 10 to 12 farms.

Agrarian Trust is now engaged with 10 farms/ranches that will create five Agrarian Commons in five states across the country. Interest, opportunity, and early stage discussions also exist between Agrarian Trust and another 15-plus farms that would create another five Agrarian Commons in five states.

The relationship between national 501(c)(3) Agrarian Trust, multiple local community 501(c)(2) Agrarian Commons, and all the leases holders provides a framework for shared and diversified support and investment into ecological stewardship, farm viability, and community opportunity. The multiple layers of the national and local organization’s relationship bring the benefits of both structures while mitigating the narrow focus of a local community or the sometimes overly broad strokes of a national campaign. The organizations and partners are dynamic, a set of checks and balances, and through these layers equity is held in land, local agrarian initiatives are given national support, and investment is made toward the stewardship of soils and ecosystems, and in reinvigorating local agrarian communities in the United States.

Agrarian Trust supports the network of stakeholders and service providers through collection and documentation of innovative models for land access. We create a comprehensive resource portal to pool the useful tools already developed, and through resource sharing and structured support, we host and facilitate the innovation and co-creation of models, structures, and tactics that aid in the permanent preservation of farmland.

Access, Equity, and Ecological Stewardship

Transforming ownership and equity of farms through local Agrarian Commons allows for the next generation of farmers to obtain access and equity, and to secure tenure. As it now stands, gross inequities within ownership and equity positions in farmland stand out as the fundamental failure that must be addressed to fully realize gains in farming and food systems development. People of color own less than 2 percent of the total farmland in this country and yet they represent more than 70 percent of the farmworker population. Farmland market value appreciation has increased 300 percent to 400 percent over the last decade in some areas, making debt financing of land even less viable.

From 2012 to 2017, mid-size agriculture lost 37 farms a day and those that survived found it is only possible with very thin margins and with the additional cushion of off-farm income and health care benefits provided by full-time or part-time employment. Small-scale farmers are required to internalize all environmental costs, investments, and remediation/regeneration with almost no support, and are forced to spend their own money and absorb the costs associated with organic certification and poor productivity of mistreated landscapes. Meanwhile corporate agriculture entities externalize all environmental costs and are the greatest polluter of soil and surface water in the country. They do not spend their own money to maintain, protect, or regenerate soils, ecosystems, or water, as they do not answer to a certifying agency that makes these additional efforts a requirement. That’s because corporate farms are able to use their power, money, and influence to push through zoning and environmental regulations.

In local Agrarian Commons, collective ecological stewardship creates a shared community engaged in sustainable agriculture, soil, ecological, and agrarian community health. The structure re-engages humans with each other, within community, and connects them back to the nourishing rhythms of the land.

Prioritizing the retention of equity and capital in local communities creates a circular flow of capital that returns to the soil, the farmers, and the communities. Aligning and structuring growth to the natural cycles of division and replication helps prevent the cancerous limitless growth of unfettered capitalist industrial agriculture. All of this brings about local agrarian sustainability that plants the seeds of cultural change.

Land in Agrarian Commons

The city of Orlinda, Tennessee, 40 miles from Nashville, had a population of 859 at the 2010 census. It is home to 540-acre Windy Acres Farm. Across the continent, South Whidbey Island, 30 miles from downtown Seattle, had a population of 14,250 at the 2007 census. It’s home to 12-acre Fennel Forest Farm, worked by Caroline Gardner. These very different regions produce two farms with very different daily experiences and culture. What the two farms do share is farmland in proximity to urban centers, and farmers who are getting old. The farmers also share a vision for their farms’ future.

The similar vision and willingness to do the work to transform ownership and equity through creation of local Agrarian Commons is what motivates Caroline Gardner to provide her farmland to launch the Western Washington Agrarian Commons on South Whidbey Island. The proximity to Seattle and the unique appeal of island land was making it more and more unrealistic for farmer ownership as the appreciated value continued to climb higher by the hundreds of thousands. Gardner’s former lavender farm will now be made available for sustainable agriculture through long-term equity lease tenure to next-generation farmers within the local community.

Alfred and Carney Farris have been pioneers in operating one of the few organic non-GMO wheat, corn, crop, and rotationally pastured cattle, sheep, and poultry farms in Tennessee. Their farm sustains a diverse and healthy mix of consumers and products in the region. Grain and corn, in most cases, require processing and production before they can be turned into a consumable product. Wheat does not go from farmer to consumer in the way a carrot can. Instead wheat needs middle-market processing and production before it can be sold to customers.

Complex farming operations such as theirs require passionate and skilled operators, but as the Farrises, now in their 80s, began looking toward transferring their land, they saw the very limited number of farmers under the age of 35. Collective community engagement could help support the farm as it continues to develop and evolve, while providing for the needs of future generations. Alfred and Carney Farris will convey their farm enterprise and land to launch the Middle Tennessee Agrarian Commons.

Windy Acres Farm and Fennel Forest Farm are just two examples of farms that are creating and launching local Agrarian Commons with Agrarian Trust. Other farms in Tennessee and in Washington are getting involved, and interest is blooming in New Hampshire. Possibilities are also developing in California, Minnesota, Montana, Virginia, West Virginia, and elsewhere. Agrarian Trust is also engaged in early-stage discussions, exploration, and collective work that will bring about more local agrarian commons in rural landscapes in desperate need of equitable transition across the United States.

Agrarian Trust is also producing cooperative learning experiences, has convened a national committee of aligned experts to inform this work, and is creating diagrams, illustrations, and art installations, using the art of storytelling to expand this work in support and partnership with others.

Regeneration Is Built One Season at a Time

It cannot be overstated how pressing and essential the work of facilitating the community transfer of pioneer farms is for the preservation of the environment, agrarian communities, and the cultures that bloom within. The culture that is connected to land, food, and community requires healthy transfers and transition from one generation’s knowledge, control, and wisdom to that of the next. Advancement in culture comes when one generation is able to build upon that put forward by the generation prior; just as regenerative agriculture practices are structured on a building process from one season to the next. This generational investment in land, ecology, farm, and community that is valued and carried forward to the next generation is a building block toward the agriculture that will reinvigorate the sentience and vitality of our living Earth.

We’ve reached the crossroads where our capitalistic model of progress has begun to dismantle our environmental and community ecologies. It is imperative that we begin to reinvest in our lands to address the long history of exploitation and the extraction of wealth from our forests, fields, and people. This reinvestment in our land must permanently donate wealth back to the land to return fertility and health to soils, ecology, and agricultural viability and to return equity to the agrarian communities who steward these realms. This reinvestment in our farms that pioneer, lead, and sustain us is ensuring a cultural independence and resilience defined by local food producing, sustainable agriculture.

The continuity developed through land transfers in Agrarian Commons allows ecological stewardship to build, grow, and evolve through the next generation of farmers. This reinvestment in land at time of transitions allows for the creation of new structures and a new reality that can liberate the people and manifest universal justice that transforms the wealth of local agrarian communities.

This is an idea worth serious consideration that offers a possibility to stabilize &/or reverse the decline of many small rural towns.

A possibility envisioned in chapter 8 of “Solar Corridor Crop System: Implementation and Impacts” (2019) Edited by Deichman and Kremer Elsevier Academic Press. Previous chapters provide the enabling basis.