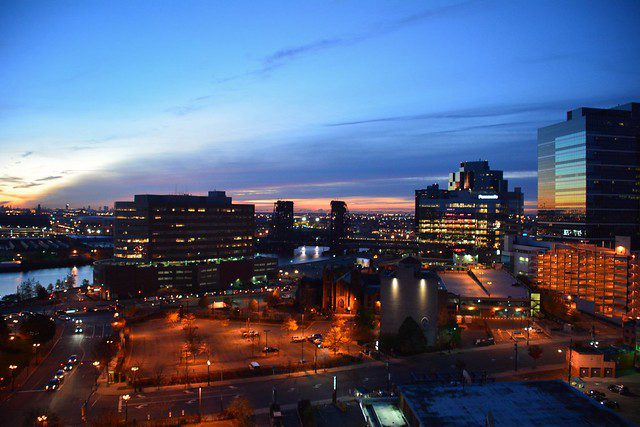

Photo by Ted Eytan via flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0

Americans are heavily geographically sorted by political leanings, with people who tend to vote Democrat living in denser settings and those who tend to vote Republican in less dense settings. For a long time, many observers have assumed this was a matter of people intentionally sorting themselves ideologically, but some recent research finds that while there’s a little of that partisan bias in moving choices, it’s actually far too small to account for the polarization that we see. In fact, it seems it’s not the people who moved, but the parties. As researchers Greg Martin and Steve Weber explain in The Atlantic, “The shift of southern whites and, later, whites without a college degree to the Republican party has left Democrats as the party of educated white voters and racial minorities. Because both of these groups tend to live in cities, the realignment has increased geographic polarization without anyone having to physically move.” They also add that, to a smaller degree, people’s politics are influenced by where they move, rather than vice versa. Combining this state of affairs with gerrymandering, which ensures that whatever polarization exists is reinforced with elected officials who swing to extremes and don’t have to appeal to a diverse constituency, cannot be helping matters.

Who attends hearings on housing development? If you’re an affordable housing developer who groans inwardly at that question, some research forthcoming from Boston University will reinforce your gut sense: Researchers found that people who are “older, male, longtime residents, voters in local elections, and homeowners are significantly more likely to participate in these meetings.” Crucially, “These individuals overwhelmingly (and to a much greater degree than the general public) oppose new housing construction.” While community development takes as a fundamental principle that community engagement is important in planning decisions, if the methods of engagement are only giving voice to one narrow (and generally more privileged) set of interests, it could be doing more harm than good.

Currently, in municipalities without source-of-income protections, landlords can refuse to rent to people using housing vouchers such as Section 8 or VASH (Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing). Effects of this discrimination were highlighted in a recent Urban Institute pilot study, which showed that voucher refusal rates are higher in areas that have not enacted local protections. Earlier this month, a bipartisan effort introduced by Republican Sen. Orrin Hatch and co-sponsored by Democrat Sen. Tim Kaine called The Fair Housing Improvement Act of 2018 seeks to address this by federally mandating source of income protections for low-income and veteran populations—adding them to other factors such as race, religion, or disability.

Could other cities learn from Nashville? As part of its plan to bring Amazon’s Operations Center of Excellence to the Nashville Yards development, the city and state did offer a lucrative package of incentives to the company, but according to an article in the Tennessean, not nearly as much as it has given to other companies like Nissan and Volkswagen with past incentives. In exchange for $102 million in combined state and city government cash grants and tax credits, Tennessee’s “performance-based direct incentives” are contingent on the company creating 5,000 jobs with an average wage of $150,000. An especially interesting part of the deal is the city of Nashville itself, which is not giving up property tax revenue as part of its incentives. Nashville’s mayor said the city would “collect those revenues back in sales tax and property taxes associated with these developments very quickly.” Meanwhile. . . in New York City.

Shelter Shorts has previously discussed the planned acquisition of health insurer Aetna by CVS Health, and this week the New York State Department of Financial Services granted final approval. The deal had been opposed by pharmacist and physician trade representatives who asserted that the merger would further lessen competition and incentive to keep drug prices low, as CVS Caremark is among the country’s three largest pharmacy benefit managers and negotiates drug prices on behalf of insurers. The companies had promised that their merger would lead to lower costs and greater access to health care through the network of health clinics within CVS stores; and in its quest for approval, subsequently agreed to not offer special pricing to Aetna-affiliated insurers in the state. Though it seems to be a growing trend, mergers and diminishing competition tend to negatively affect consumers, and when it pertains to health care, the consequences harm more than just the wallet.

What we’re reading. An op-ed in City Limits on the New York City’s new Right to Counsel law, with this energizing quote: “We also understood right to counsel (or RTC) as a racial and economic justice struggle. Right to counsel stops evictions, but it also creates space to organize and build tenant power to win bigger and bolder demands. It moves tenants who are in danger of leaving our city to the center. At its core it’s about building tenant power in our city.”

Comments