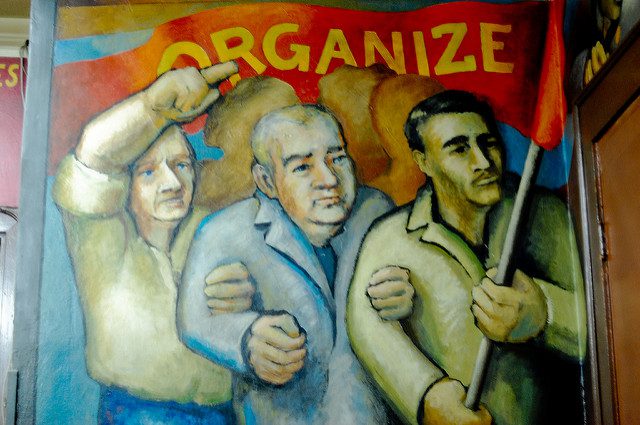

A mural that depicts the history of the United Electrical Workers Union. It was painted in 1974 by John Pitman Weber. Photo by Eric Allix Rogers via flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“There is no substitute for bottom-up organizing.”

No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age by Jane McAlevey is a superb analysis of what works and what fails in organizing social movements. The book is based on the author’s own extensive experience in community organizing and work in the environmental justice movement, as well as 12 case studies from which she constructs a comprehensive model of how to succeed in organizing. McAlevey’s focus is primarily on union work, but her analysis also applies to community organizing and electoral work.

In more recent years, McAlevey has been deeply involved in union organizing and negotiations. Her first book, Raising Expectations (and Raising Hell), co-authored by Bob Ostertag, was named the “most valuable book of 2012” by The Nation magazine. She has since earned a doctorate from the City University of New York’s Graduate Center, studying with Frances Fox Piven.

Make the Road New York, an immigrant justice group, is also highlighted in the book for its mass collective action, which it views as essential to success. The group has successfully fought widespread wage theft and was instrumental in ending New York City’s cooperation with Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) due to its systematic violation of civil rights among New York’s immigrant populations.

McAlevey situates the successful work of these unions within the context of the “new labor” approach of the last 40 years. The workers of Smithfield Foods, the immigrant population that Make the Road New York mobilizes, as well as teachers in the Chicago Teachers Union, all rejected the new labor approach (“pragmatic” business unionism that does not engage and empower the rank and file), which has disempowered the majority of workers.

McAlevey claims that “the greatest damage to our movements today has been the shift in the agent of change from rank-and-file workers and ordinary people to cape-wearing, sword-wielding, swashbuckling staff.” On the other hand, the success of the aforementioned groups is largely due to their rejection of the new labor approach and their adoption of CIO-style (Congress of Industrial Organizations) organizing, a successful worker organizing method of the 1930s and 1940s that included engaging the majority of workers, the development of organic leaders into organizers, and an ethos anchored in class struggle.

Change Processes

One of McAlevey’s insights is her breakdown of three broad types of change processes: advocacy, mobilizing, and organizing.

Advocacy doesn’t involve ordinary people in any meaningful way. Instead it relies on professional technocrats (lawyers, pollsters, researchers, communication firms, etc.). This approach has become more common over the decades as unions and other mass-based organizations have atrophied. Advocacy groups have many successes under their belts but they fail to use the only concrete advantage that ordinary people have over elites: large numbers.

Over the past few decades a newer mechanism for change has evolved: mobilizing. McAlevey sees mobilizing as a substantial improvement over advocacy because it brings large numbers of people into the fight. It is facilitated by 21st century social media and is well-suited for the looser connections and declining older forms of social capital documented by political scientists and sociologists such as Robert Putnam and Robert Wuthnow; but more often, mobilizing brings out the same people over and over. A professional staff often directs and controls the mobilization, and the people who show up at protests, marches, and vigils have no part in developing a power analysis or strategy.

Organizing, on the other hand, places the agency for success with a continually expanding base of ordinary people with the goal of transferring power from “the elite to the majority, from the 1 percent to the 99 percent.”

A key element in successful organizing is leadership identification. Every bounded group, whether it be a workplace, church parishioners, or a neighbor threatened with displacement, has individuals who are respected by others in that community and who are natural leaders. Identifying these leaders, understanding their concerns, and finding a way to work with them are important elements in organizing for success.

Many of the successful organizations studied by McAlevey had to make the bold move of rejecting past practices. McAlevey recounts several instances where new union leadership insisted on throwing out the ground rules that traditionally handcuffed them in negotiations. Strict limits on who can participate in negotiations, and “agreements” not to discuss the content of meetings always work to the disadvantage of the union. This was one of the keys to success for 1199 NE, a Service Employees International Union representing 20,000 health care workers in New England.

To effectively activate the power of their constituency, unions and community organizations must make it clear that they are not for-service entities. They cannot be seen as a third party alongside workers and management, they must be the workers. Another vital element is engaging the broader community. “… when a union strategically engages the broader community, new and strong leaders develop within and outside the factory walls.” The same organizing methods should be applied to the broader community that are used with the workers simultaneously, “as a seamless, unified approach.”

How Do You Win When Your Major Weapon—the Strike—May be Illegal?

Thoughtful rejection of imposed constraints was one key to the success of the Chicago’s teachers strike in 2012. Self-education, militancy, intensive efforts to build community ties and support, a broader perspective that included a critique of growing inequality, racism, privatization, and other social issues that go beyond salaries and working conditions, were all part of their daring and successful strategy.

The forces of conservatism have engaged in a 50-year war that has played a big part in the increasing distrust in government, journalism, unions, and many other social institutions. This distrust has resulted in a fracturing of working-class unity and a growing ideology of self-blame.

The lesson of No Shortcuts is that overcoming the ideology of individualism and self blame, as well as corporate power, is achieved not through framing or advocacy but by deep organizing and “through the experience of collective struggle.”

Comments