Seattle is becoming more diverse and multi-ethnic, while some of the city’s historic and longstanding neighborhoods such as the Chinatown/International District with high proportions of color are seeing people leave. Photo courtesy of John Beutler

“I do love Seattle. I love the people here. I love the environment. I love [that] it’s fast paced and slow. I love that you can have a family and still be an entertainer in the community and make it work.”— J.O., a participant of the Seattle Public Library’s “Sharing Our Stories” project.

That’s true that Seattle, until recently, has offered opportunities for households and families across the income spectrum. The city is, however, also changing rapidly. Between 2016 and 2017, the city added 75 residents a day. While the influx of people coming into the city is affecting most Seattle residents, it’s hitting communities of color particularly hard.

Seattle Public Library’s “Sharing Our Stories” project collected first-hand accounts of community change from 2014 to 2017. The project focused on neighborhoods that have experienced significant change, such as Capitol Hill and the Central Area, and on demographic groups that have been more seriously affected, such as African Americans and the LGBTQ community.

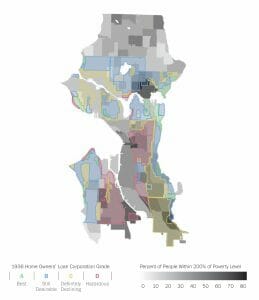

Seattle is seeing growing disparities between the lower and higher-income populations, and historic and geographic trends of isolation and segregation along race continue. Several neighborhoods that overlap with historically redlined areas are experiencing severe cultural losses where displacement pressures disproportionately affect communities of color. The complex dynamics playing out in Seattle neighborhoods, which can only be partially understood through data, is inviting the City of Seattle’s attention in unique ways.

In one first-hand account, J.Y., a Central Area resident, reminisces:

“People you grew up with and went to school with . . . you see them become successful. . . and you support them and the wonderful things that they’re doing . . . . It should be that way for everybody. Unfortunately, it’s not. We have so many issues impacting our community now. The No. 1 thing is the level of poverty. We had poor folks then, but somehow I sense that the difference between poor and the not poor is huge. You can’t bridge it.”

J.Y.’s speculation about rising income inequality is accurate. Over the last decade and a half, while Seattle has seen a reduction in the share of households making moderate and lower middle-incomes (between 30 and 80 percent of the area median income, or AMI), there was a considerable increase in the share of high-income households (above 80 percent of AMI).

While some income variation is common in a functioning economy, the widening gap and the racial dimension of the disparities—including a strong correlation between low-income communities and communities of color—are alarming and vexing for Seattleites.

“African Americans and other ethnic groups don’t feel the energy that was once there. It’s been said that it’s going to be for the betterment [of Seattle]. Well, that might be true, but when the playing field is not even . . . people can’t buy homes anymore; they can’t afford to pay rents. People are out on the street. Granted, we’ve had people on the street [before] now, but there was always some place for them to go,” says G.H., another participant of the library’s “Sharing Our Stories” project.

While the salaries of lower-income groups have been plateauing, their housing costs have risen significantly. In the last five years, average rents have increased more than 50 percent in several neighborhoods. Three quarters of low-income renter households in Seattle are cost burdened, or paying more than one-third of their income on housing. Half of the cost-burdened, low-income renter households pay 50 percent or more of their income on rent.

The main reason for the explosion in rental costs is an insufficient supply of units in the face of population growth. This increases the vulnerability of lower-income households because they must compete with higher-income households for homes.

While high-end homes, specialty eateries, art galleries, and nightclubs in downtown and adjacent neighborhoods have been created with fervor and speed, housing and services for a low-income clientele, with lower-price points and with resulting lower-profit margins, have often lagged.

Newly constructed homes included in Seattle’s massive construction boom are typically offered at 20 percent-higher-than-average rents. And lower-income households are finding it difficult to find housing even among older homes. Research shows that only 2.5 percent of the existing unsubsidized housing is affordable to very low-income households (those who earn less than 50 percent AMI).

This situation is causing various forms of displacement that is disrupting communities of color across the city.

Forced to Move

Since the data we collect to measure residential displacement does not always explain why a person moved, it is difficult to distinguish displacement from a move by choice. Residents with stagnant incomes are vulnerable to even modest increases in rent. Longtime homeowners who are unable to meet housing expenses can also often be left with an unavoidable choice to sell their homes in times of hardship.

The city’s growing disparities are visible in Seattle’s geography of low income households and communities of color and trace the historic areas of redlining. Courtesy of the City of Seattle’s Office of Planning and Community Development

“My uncle owned that apartment building for a long time . . . right there on Jackson. There must have been 30 or 40 families that had to move, got displaced when my uncle was forced to sell the building as part of a ‘fair settlement’ after the building was deemed condemned. And now what’s there? Businesses and some condominium stuff that were out of the price range of the people to buy back in.

“I moved out of Madrona [a Seattle neighborhood], and we couldn’t move back in . . . It would cost us three or four times what our house was valued at. That’s what happens. Everyone was thinking, ‘Let’s move away from the Central Area,’ not realizing how valuable [it was] in terms of the geographical location. I mean literally, you’re within minutes of downtown Seattle. You take one bus and you’re there,” says J.Y.

In 2015, city officials did an in-depth Growth and Equity analysis as part of the Seattle 2035 Comprehensive Plan. The analysis identified high displacement-risk areas as having higher proportions of marginalized populations, such as people in poverty, people of color, and households that speak a language other than English.

Of the 610,000 people living in Seattle in 2010, approximately one-fourth lived in urban villages associated with a high risk of displacement. Urban villages, which roughly include a population of 210,000, are centered on transit and amenities in the city, and have been identified as locations to absorb future growth.

While the city is planning for a lower level of growth in urban villages with high displacement risks, one such village, the Central Area neighborhood, points to the changes currently happening in such areas. In 1990, the African-American population in the neighborhood was three times the population of whites. By 2000, the African-American population had dropped by half. The white population in the area, on the other hand, doubled. Other changes in the neighborhood included an increase in incomes, levels of educational attainment, home values, and housing-cost burdens.

The Growth and Equity analysis also measured access to opportunity based on neighborhood amenities and places where positive life outcomes are more likely—higher school performance and graduation rates, higher incomes, and wealth creation. The displacement-opportunity typology, though limited in telling the complete story, begins to capture some differences across the city where displacement is most likely to occur in the future, and how patterns of opportunity are not evenly distributed.

Over the past 25 years there have been large reductions in the proportions of African Americans in the high-displacement risk areas that include north Rainier, in addition to the Central Area. At the same time, the white population has increased significantly in these areas. In other neighborhoods, including all census tracts north of the ship canal and in the western parts of the city that lie across a spectrum of displacement and opportunity, white population percentages have dropped. Hispanic and Asian populations have been growing across the city although more significantly in low access to opportunity areas, particularly in Southwest Seattle. Overall, the city is becoming more diverse, but some of the city’s historic and longstanding neighborhoods with high proportions of persons of color are seeing the latter leave.

While direct displacements that typically involve building demolitions are highly visible, their proportion is relatively small. In contrast, displacement by less overt economic pressures is much greater. Direct displacements accounted for, on average, about 200 households per year, whereas shifts in demographic composition at the census tract level in income and race categories comprised changes in the tens of thousands, some that can be anecdotally associated with economic displacements.

There seems to be a regional shift where economically displaced households have moved to more affordable parts of King County. Although this assertion cannot be confirmed definitively with data, it is consistent with stories like J.Y.’s.

Amidst the narratives of displacement and income inequality, it is encouraging that there has been relative stability in the presence of extremely low-income households (who have incomes below 30 percent AMI) in Seattle. One reason is the progress that the city has made in building an infrastructure that meets the housing needs of very-low-income households (50 percent AMI) and below. In the last 36 years, the city has invested nearly $450 million in the creation and preservation of more than 14,000 affordable rental homes. It has also provided emergency rental assistance to 6,500 households.

The reduction in displacement pressures due to overall construction activity has been, however, tricky to fully unravel in Seattle’s context. As researched elsewhere, even while new housing construction has helped moderate rent increases on a citywide scale, we do not have data to confirm if or how the building activity has relieved the housing pressures for lower-income groups at the neighborhood level.

Displacement may also begin several decades before a neighborhood experiences new market-rate development. For example, the current displacement of the African-American community from the Central Area began as early as the 1980s, when the neighborhood was severely underinvested and newcomers, small-scale investors, and artists took advantage of the area’s cheaper housing and purchased homes in the area before the wave of market-led redevelopment took hold in the late 1990s. Several residents were either evicted or faced increased rents when the properties changed hands. We can likely see similar patterns of this “quiet” displacement playing out today in communities further south, such as Rainier Beach and South Park.

Another revealing statistic is that increased housing production at the census tract scale in Seattle is not associated with a loss of low-income populations between the 2000 and 2010 timeframe. It is instead concurrent with increases in both low-and middle-income households. When considering for race, there exists a moderate correlation with changes in the white population, but the correlation is not significant for African-American population or Hispanics more broadly. But since we know about the loss of these latter groups in high-displacement risk areas, we can conclude that factors aside from housing production are likely at play with respect to displacement of these groups.

Cultural Changes

When people are displaced, they don’t only lose their homes, they also lose their communities. Displacement frequently means a transition for the displaced household to an area outside the neighborhood with fewer opportunities and sometimes with even greater cost burdens, such as the increased transportation expenses for J.Y.’s family. While a loss of wealth can follow when a household is left with no option but to sell, there can be wider impacts on the community. Displacement deepens segregation and perpetuates conditions of housing instability that can have serious health, educational, and economic outcomes. Education for children can be disrupted, there is likelihood of greater joblessness, and families can be reduced to a state of stress and anxiety. As more communities of color are impacted, neighborhood polarization and friction can heighten to the point where neighborhood revitalization becomes good news for one part of the community, but creates hopelessness for another.

Seattle is becoming more diverse and multi-ethnic, while some of the city’s historic and longstanding neighborhoods such as the Chinatown/International District with high proportions of color are seeing people leave. Photo courtesy of John Beutler

It can be a mixed bag. For M.M., the new groups in the Central Area today have reinforced the sense of community and enhanced the vitality of the neighborhood grocery store. “They bind together and they help one another.” The loss of older groups and families coupled with the loss of homes and old stores, however, is also much visible.

“As the economy gets better, it’s actually pretty good. It’s fun. When you’re a people person, it’s good to meet lots of new, different, diverse people . . . It’s been really exciting seeing the change. It’s been sad, in some senses, in seeing some of the people pushed out, and some of the businesses that are struggling to make it. But it’s also encouraging to see the future in the Central Area . . . I just hope we don’t lose the diversity, we don’t lose the history, [and] we don’t lose what the Central Area was built on,” M.M. says.

G.H. remembers Jackson Street being the center of a vibrant, working-class, multiracial community. Many people were employed at companies like Todd Shipyards, Bethlehem Steel, Boeing, and Sears, and the families were tightknit. People walked to barbershops and enjoyed the soul food cuisine offerings at establishments run by other families who lived in the neighborhood. Customers used the honor system at Jesse’s Grocery Store on 28th and Jackson, and “simply signed . . . credit. And they knew who you were, and they knew they were going to get their money.”

G.H. also remembers people who worked not from a position of what was best for them, but what was better for the community; people who were excited to mingle and learn from each other at a variety of social venues, whether during informal encounters at the grocery store or during a planned visit to the neighborhood library. These places served as the families’ living rooms.

“The librarian, or somebody that was working there, knew my whole family. And you’d hear, ‘Well, how’s your mom?’ or ‘How’s your dad? . . . Tell ‘em I said hello.’ See, all that is lost,” says G.H.

While neighborhood stories from the Central Area evoke nostalgia, they also obscure the negative realities of crime and safety that plagued the neighborhood in the 1970s and after when storefronts were boarded up and people felt unsafe on the streets. Starting from such a place, neighborhood changes can improve livelihoods of existing residents, offer opportunities such as access to better grocery stores and pharmacies, and reinforce mutual support and a stronger sense of belonging and identity for longtime residents.

But when a tipping point is reached, significant changes can also hurt neighborhoods. In a manner similar to residential displacement, commercial displacement can cause longtime businesses to leave. With a new resident population that may have different needs and lifestyles, more luxurious stores may compete for the available commercial spaces and can drive up rents. National chains and stores can disturb the ecosystem of decades-old mom and pop stores about which people like G.H. so fondly reminisce.

The community networks and the cultural capital built over the years in neighborhoods such as the Central Area and the Chinatown/International District can also be transformed with a greater emphasis on products and services for new residents. If the latter are only interested in the offerings and disengaged from the broader community, the process can isolate longtime residents or make them feel unwelcome. The business districts dominated by restaurants and shops that offer ethnic cuisines and artifacts but lack hardware stores and other services can generate a local economy based on entertainment and tourism, one that is associated with higher risks for local businesses and low-wage and seasonal jobs for its workers.

Where improvements benefit newcomers solely or primarily, longtime residents can find themselves excluded from their own communities. Cultural venues that invited residents to mingle and celebrate festivities can get closed when new residents raise noise concerns, and local preferences for vitality and informality can get overshadowed by new aesthetic preferences codified in new standards against blight and nuisance. Neighborhoods may undergo a certain hollowing-out phenomenon where outside dominant worldviews homogenize a unique local culture and may permanently diminish a community.

Redlining and racial covenants segregated Seattle and marginalized certain racial groups in the middle of the 20th century. However, those marginalized communities cultivated and nurtured their own cultural capital that supported the members during times thick and thin. These communities now risk losing that support as high-income households are attracted to the cultural offerings and centrality of these neighborhoods.

The collapse of an ecosystem of historic businesses that was built around mutual community support ultimately fractures the collaborative foundation that allowed the businesses to build a clientele in the first place. When businesses close or move elsewhere, it diminishes not only the chances of remaining businesses, but also the cultural capital of residents such as G.H., whose social networks were shaped through encounters at local stores.

“If we don’t do something about the level of poverty, and the gap between the haves and the have-nots, we’re headed for total desolation. If we can’t figure out a way to bring that segment of our society into the fold, how can we advance as a nation? How can we move forward if we can’t embrace the folks that are not with us?” says J.Y.

The City’s Strategies to Fight Displacement

The Seattle Library’s project asked participants, “If you could focus all the energy and resources around the change happening today in Seattle, and use it to shape the city into a place of your dreams, what would it look like?” Some responses included:

“A Seattle where everybody is content with where they are, and they’re able to be where they want to be without any kind of fears of being picked out,” says V.M.

“Public transportation that’s easy and affordable,” says L.B.

“More public spaces that give people opportunity to come together in a way that’s more inclusive,” says I.S.

“People would embrace all of the astounding amounts of difference that are here. Gentrification would stop being so awful. People would actually unite and combine and mix and mingle,” says L.B.

Similar to the rest of the country, Seattle is growing more diverse. Its added diversity gives the city another chance to uphold the promises of the American dream—to empower the different people that collectively create progress.

Seattle sees itself as a partner in this. The city’s investments and priorities have been bolstered since the recognition of its own role in the “structural racialization” that isolated and marginalized people of color. Through the 1980s and 1990s, several city departments organized efforts to address racial disparities and while there was some success in making the city a relatively diverse workplace, it was continuously hit with the same question: “In such a diverse, progressive, and prosperous city, why do all the key life indicators (income, health, education, criminal justice, etc.) fracture along a racial fault line—and more important, how can we achieve different results?”

The city moved its focus to stem institutional racism.

Seattle engages with residents through focus groups for the Mandatory Housing Affordability within the Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda. Photo courtesy of the City of Seattle

Seattle launched a Race and Social Justice Initiative in 2004. Its premise is to create systemic change in the city’s institutional practices to “eliminate racial disparities and achieve racial equity in the city.” The city has since partnered with organizations, communities, and private and philanthropic sectors and is making changes and tracking progress across city departments.

The city’s strategies are currently operating at two levels—place-based and people-based. Place-based actions are more often associated with building and physical infrastructure improvement—better housing choices and affordable transportations options, and sufficient access to schools, libraries, healthy produce, and health centers—for everyone, but more narrowly for Seattle’s at-risk city dwellers.

While most prevalent in high-displacement risk areas, Seattle’s marginalized communities of color live throughout the city. Therefore, some of the city’s actions can also be understood as “people based,” which will elevate the change for better life outcomes for marginalized residents, including the homeless, youth, and the formerly incarcerated. Some actions are simultaneously place-based and people-based.

Unlike many cities in the U.S. that bypassed low-income neighborhoods in their locations of mass transit stops, over the last decade Seattle made strategic transit investments in the region’s most racially and income-diverse communities that were historically segregated along auto-oriented arterials and experienced under-investment. These transit stops, however, have also attracted speculative development activity in recent years and have increased displacement pressures for communities living in these areas.

To address these challenges, the city is employing a huge number of strategies, from mandatory inclusionary housing to business development programs that support low-income and immigrant-owned businesses to a Cultural Anti-Displacement Fund that supports arts and cultural groups at high risk of displacement in efforts to attain facility ownership. These strategies build upon the understanding of not only where marginalized populations are located but also what their unique needs and challenges are.

The Mandatory Housing Affordability program is a new requirement that developers contribute to affordable housing whenever they build within urban villages and multifamily and commercial areas in the city. The program, currently in place in several locations, has sensitively approached high-displacement risk areas. While balancing the need to make the program attractive for developers and extracting affordability in exchange, the city has carefully crafted zoning changes that minimize impacts and changes in high-displacement risk areas relative to other areas in the city. With urban villages in these areas that have mass transit stops, the higher upzones, or areas with higher development capacity increases, have been limited to only a five-minute walk of the transit stop.

Developer contributions are also proposed to be more in high-cost and high-displacement risk areas, such as the Central Area. Overall, the high-risk displacement areas will not only benefit directly from developers’ contributions of on-site affordable housing, the program will also prioritize investing of in-lieu payment contributions in areas where they are most triggered. This will encourage affordable housing everywhere new development happens, and will benefit places such as the Central Area, which in the absence of affordable housing investments, can otherwise transform in more serious ways.

Seattle is also working with ideas and initiatives that are community driven. The Equitable Development Initiative is primarily focused on capacity building among local community groups and prioritizes efforts and investments in high displacement risk areas such as the Central Area, the Chinatown International District, Rainier Beach, and the Duwamish Valley. For the Chinatown International District, the city is currently facilitating a separate conversation that was initiated by the community. The effort is not only validating the personal and community-based experiences of those most impacted, but also engaging people to create pathways that center on community’s priorities.

The city’s efforts, while focused on equitable and multifaceted approaches, haven’t yet completed the task of reconnecting all marginalized populations to housing opportunities that have access to good jobs, high-performing schools, robust transportation, and quality parks and health care facilities. The city is still very much living in the shadow of deep mistrust among many of the marginalized groups.

As Seattle tackles the displacement challenge, however, we can all learn that universal well-being is closely associated with expansion in opportunities for the marginalized. By continuing to reduce the systemic and structural barriers in connecting marginalized populations to opportunity and to other residents in the city, and by reinforcing and acting from a shared responsibility to one another, we can take deliberate steps to make the future better for us all.

I had hoped this article would actually define and detail the strategies and practices the City of Seattle was undertaking to “take ownership of its displacement challenge”. Yet, not only are “people based” strategies not defined outside their supposed creation of “better life outcomes for marginalized residents, including the homeless, youth, and the formerly incarcerated”, there is no account of what the progress being tracked has been since Seattle’s 2004 launch of a Race and Social Justice Initiative to “create systemic change in the city’s institutional practices to “eliminate racial disparities and achieve racial equity in the city.”” Also the author remarks that the city is undertaking “a huge number of strategies” and then mentions 3, of which only one (the Equitable Development Initiative – established 12 years after the Race and Social Justice Initiative) has seemingly provided direct resources to communities now well-experienced in displacement and gentrification. Local analysis of the MHA and the HALA initiative are mixed on potential impacts on displacement & gentrification in a city where development and growth are already concentrated in a few neighborhoods (https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/data/some-seattle-neighborhoods-are-untouched-by-rapid-population-growth-why/).

My guess is whatever progress alluded to since 2004 has been largely limited to the 10+ year later analysis of high-risk displacement communities, “philanthropic partnerships” and the pablum above. Real equity means acknowledging and making right past wrongs, and shifting power and resources to the so-called “marginalized”, not to continue to treat those historically ignored and systemically discriminated against as peripheral to anti-displacement work — to be called upon to offer “nostalgia” in focus groups and story sharing sessions — while real policy and systems change work is only delayed and denied. “The city is still very much living in the shadow of deep mistrust among many of the marginalized groups” – indeed this article only further proves why that continues to be so.

TL;DR: This reads like an ad for Seattle City Gov., the author’s ex-employer. Shelterforce please have better analysis and research!

VG: Thanks for your thoughts. My responses are below.

Comment: I had hoped this article would actually define and detail the strategies and practices the City of Seattle was undertaking to “take ownership of its displacement challenge”. Yet, not only are “people based” strategies not defined outside their supposed creation of “better life outcomes for marginalized residents, including the homeless, youth, and the formerly incarcerated”, …Also the author remarks that the city is undertaking “a huge number of strategies” and then mentions 3, of which only one (the Equitable Development Initiative – established 12 years after the Race and Social Justice Initiative) has seemingly provided direct resources to communities now well-experienced in displacement and gentrification.

VG: Ownership for me begins with understanding the breadth and depth of the challenge. Seattle is among the very few cities to base their comprehensive planning efforts on a framework of displacement and opportunity. Your later assertion about the City’s “analysis of high-risk displacement communities” in this regard is correct.

In its vision for growth, the Seattle 2035 Comprehensive Plan, prioritizes attention for areas and communities that are most negatively impacted, and ultimately “aims to give all Seattle residents better access to jobs, education, affordable housing, parks, community centers, and healthy food”.

Similarly, in the 2017 Assessment of Fair Housing, the City has documented how it will uphold Fair Housing laws and work to support all residents with equal chances to access housing opportunities, and remove barriers where necessary.

While there are some success stories in Seattle (as following sections will illustrate) the path toward implementation is undoubtedly challenging since American city systems are based on old models of economic development and decision making where actions can sometimes get inadvertently misaligned with the initial intentions of plans. The need to balance aspirations with vigilance is crucial and I believe Seattle’s City Council has presented a high level of accountability on a variety of issues.

The needs are also far too many while resources have been limited. City efforts have reached some communities but not everyone. And the City’s planning horizons are much longer, as in the case of the Comprehensive Plan with a twenty-year time span, and it does not have all the results yet.

The article’s word length limitations unfortunately precluded including a discussion of people-based strategies and several of other place-based strategies. I am including a few additional here. These are by no means exhaustive and people who have attended MHA community meetings held over the last year will find these references familiar.

People-based strategies

To address homelessness the City worked to locate a navigation center that is working as an interim one-stop center for the homeless and their families before transitioning to permanent housing. The City also has programs such as the Seattle Conservation Corps that provides job training and counselling services to formerly homeless adults.

The City is supporting Youth Employment Services and other job training programs that are equipping Seattle’s youth to seek employment opportunities with living wages. For their recreation needs, the City is funding free or low cost drop-in activities that include tot gyms, fitness rooms, basketball, and table games.

For communities of color, who face disproportionate housing burdens, the City is offering protections for use of Social Security Income, child support payments, veterans’ benefits, and other non-traditional income sources for housing payment. Further, the City is engaging in proactive enforcement of these protections through outreach to communities most likely to face discrimination and by educating landlords. As part of HALA’s MHA and MFTE programs, the City will require that developers ‘affirmatively market’ the dedicated affordable units to further fair housing. This means developers are required to provide notice and outreach specifically to historically excluded communities wherever the affordable housing is located.

Seattle is also making efforts to reduce barriers to housing for persons with criminal records in accessing housing through the Fair Chance Employment ordinance. More broadly, the City is working on several talent-development strategies that position under-served communities to access advancement opportunities throughout their career paths.

To support the power and agency of local communities, Seattle is leading efforts to ensure all the city’s outreach activities reach communities where barriers have led to historical lack of participation. The City is working to bring services and programs to places where disadvantaged communities of color congregate, such as the Seattle Goodwill headquarters or the Ethiopian Community Center. Where needed, the City is equipping emerging leaders with tools such as leadership training and training in communication, facilitation, and storytelling. The City is also continuing to work to create new and improved ways of community partnership and engagement through emerging tools such as online forums, story mapping, and using demographic and language-specific venues.

Additional place-based strategies

The City’s area planning efforts are focusing on local neighborhoods and involve identifying neighborhood-level priorities such as housing, transportation and park needs, and the supporting community assets that city residents such as the Library project participants desire. City departments with their areas of expertise are contributing to implementation efforts in the prioritized areas sometimes independently and sometimes based on interdepartmental collaboration.

The City’s Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA) is one such interdepartmental partnership. Recognizing that the public and non-profit sectors alone can’t solve the housing affordability challenge, the City also partnered with private housing providers. Focused on making Seattle more affordable, HALA includes more than sixty strategies such as MHA and MFTE that will expand affordable housing options for the city’s marginalized low income communities and communities of color and the homeless, but also that more broadly will increase the supply of homes across the city. The expanded Multifamily Tax Exemption (MFTE) program offers tax incentives to developers to make a portion of their units affordable to low-income households.

Many of these strategies address displacement pressures. HALA is the new addition to the City’s portfolio of housing strategies, including those that have continued to offer low interest loans to build an infrastructure of rental and owned homes and that reach across neighborhoods throughout the city.

To better ‘connecting people to resources’, Seattle is continuing its work to build transit investments such as light rail, street car and bus rapid-transit lines. The City is making strategic improvements in the region’s most racially- and income-diverse communities, those that historically were segregated along auto-oriented arterials and experienced under-investment. With additional funding in place, the City is working to provide within eight years a rapid transit stop within a ten-minute walk to almost three-fourths of Seattle residents. For shorter-distance connections to schools, parks, libraries and grocery stores, the City is continuing to prioritize improving sidewalks as well as other easy transit connections and restoring pedestrian safety.

These improvements will enhance everyone’s access to transit and transportation choices. Where there are gaps, such as the Greater Duwamish neighborhood, the city is working to improve access through planned rapid transit improvements.

Supporting existing and new public and semi-public spaces is also central to the City’s planning. These places promote human connections beyond the lines of race and income. While access to opportunities is crucial, as noted in the Library stories, historically marginalized communities also need to connect to other residents.

Additionally, new arrivals in the city’s community of color neighborhoods must adapt to existing neighborhood norms and traditions that can reduce friction and divisions around differences in racial and income backgrounds. Seattle Parks and Recreation’s provision of free and low-cost access to facilities such as parks, community centers, teen-life centers and pools offers a variety of venues that provide respite for everyone for purposes of recreation, relaxation, and rejuvenation.

These facilities also provide for the interaction of neighbors with diverse backgrounds and are contributing to greater acceptance and tolerance. To prioritize the needs of at-risk communities, the City uses a race- and income-based standard for selecting major maintenance projects.

Within the semi-public realm, supporting small local businesses, such as stores and restaurants, is an important part of efforts to stem cultural displacement. The City is supporting local businesses, particularly those owned by low income and immigrant communities, so they can serve long-term clientele and adapt to the needs of new patrons. Local businesses can thrive and provide interactive spaces that can be inviting to everyone in the community.

In the effort to support these businesses, the City is offering technical assistance including mobile business consulting, alternative financing, and marketing, and building and supporting business leadership. The Only in Seattle program provides grants to neighborhood business districts for organizing, business development strategies, and marketing. The City is also supporting small businesses by providing assistance around specific needs, including creation of small and affordable spaces and prioritization of women- and minority-owned businesses, as currently being piloted in the Chinatown-International District and in Pioneer Square.

To directly support the preservation of cultural capital in historic communities such as the Central District, the City is working to protect and provide affordable commercial spaces for private and non-profit organizations. These include working spaces for artists’ studios, rehearsal rooms, recording studios and sound stages. The City is supporting these organizations through direct funding for capital projects and operating expenses.

Seattle is currently developing a Cultural Anti-Displacement Fund to support arts and cultural groups at high risk of displacement to attain facility ownership. Similar to the support offered in business districts, the City is employing technical assistance and coordinated marketing campaigns that celebrate culturally-rich neighborhoods and that offer more self-direction to existing communities and a less commodified feel to newcomers. Such strategies are helping build strong communities that can withstand the disruptive forces of displacement.

Comment: what the progress being tracked has been since Seattle’s 2004 launch of a Race and Social Justice Initiative to “create systemic change in the city’s institutional practices to “eliminate racial disparities and achieve racial equity in the city.” … My guess is whatever progress alluded to since 2004 has been largely limited to the 10+ year later analysis of high-risk displacement communities, “philanthropic partnerships” and the pablum above.

VG: This is ongoing work for the City to evaluate its progress made and to course correct. Here are a few resources that highlight some of what the City has accomplished.

These document achievements made in specific time periods: 2009-2011, 2012-2014, and 2016, and an overall summary.

If people have ideas about what the City can be doing additionally or differently, I will encourage them to join the City’s race and social justice community round table.

Comment: Local analysis of the MHA and the HALA initiative are mixed on potential impacts on displacement & gentrification in a city where development and growth are already concentrated in a few neighborhoods (https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/data/some-seattle-neighborhoods-are-untouched-by-rapid-population-growth-why/).

VG: MHA and the associated zoning changes alone are not going to solve the housing crisis. The City’s HALA framework has more than 60 recommendations. These will need to be carefully prioritized for neighborhoods relating to their densities and built form. As an example, the changes under consideration for the City’s Accessory Dwelling Units policy have the potential to add housing for the missing middle throughout the city.

Comment: Real equity means acknowledging and making right past wrongs, and shifting power and resources to the so-called “marginalized”, not to continue to treat those historically ignored and systemically discriminated against as peripheral to anti-displacement work — to be called upon to offer “nostalgia” in focus groups and story sharing sessions — while real policy and systems change work is only delayed and denied.

VG: The previous section of the response highlights systems change work happening in Seattle since the launch of the Race and Social Justice Initiative that, as I previously stated, was where the city recognized “its own role in the ‘structural racialization’ that isolated and marginalized people of color”.

Seattle has been the first city to take many progressive actions to help marginalized and impoverished communities. The City passed the nation’s first $15 minimum wage legislation and required paid sick leave making it possible for those with lower incomes to afford the basic essentials. The City has expanded funding for preschool to allow more children to get early education. The current housing levy, which was one HALA recommendation, builds on Seattle’s previous successes of housing levies and is double of the previous one. The housing levy is frequently documented, as a recommended model for other regions like the San Francisco Bay Area to consider.

Seattle continues to make headlines, and the work of progress is a work in progress. The employee tax was novel but unfortunately did not last. Or the idea of municipal socialism, under consideration. Or the Airbnb tax that would fund the City’s EDI strategy, a community-led priority.

Comment: “The city is still very much living in the shadow of deep mistrust among many of the marginalized groups” – indeed this article only further proves why that continues to be so.

VG: Seattle is seeing growing disparities and its historic trends of isolation and segregation continue. Its efforts, while focused on equitable and multifaceted approaches, haven’t yet completed the task of reconnecting all marginalized populations to housing opportunities and creating access to good jobs, high performing schools, robust transportation, and quality parks and health care facilities.

In the past, Seattle residents have advocated and won on many issues from the $15 minimum wage and paid sick leave mentioned above to housing and transit levies. The city has not yet exhausted its possibilities for forging stronger partnerships with stakeholders on initiatives that empower and support all marginalized communities. It is “still very much living in the wake of deep mistrust among many” of them.

The city can however benefit from its citizens’ support and creative ideas to continue to guide it on the way forward, to correct its actions where it is faltering, to bolster it where may be on shaky ground, and to help shape Seattle as a place where every resident can live, work, and enjoy a rewarding and productive future.

It is, however, also true that we are not talking enough about best practices everywhere and elevating them even where they are exemplary as in Seattle. There are definitely gaps, and specific ideas for course correction will always help.

Comment: TL;DR: This reads like an ad for Seattle City Gov., the author’s ex-employer. Shelterforce please have better analysis and research!

VG: The original article and this comment response offers a glimpse of Seattle’s efforts, some of which are unprecedented in the United States. I am humbled and proud to have had an opportunity to work with Seattle and wanted to use a medium beyond a 140 character shout out to share what I learned while in Seattle and what I was continuing to work on until the time I left. I am thankful to Shelterforce for letting me do that and adding to their wealth of critical ideas and perspectives. Thanks to the commenter for reading Shelterforce and for presenting me with an opportunity to provide further reflections.