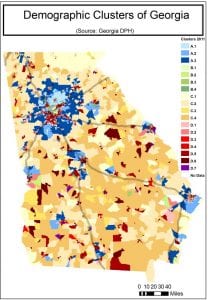

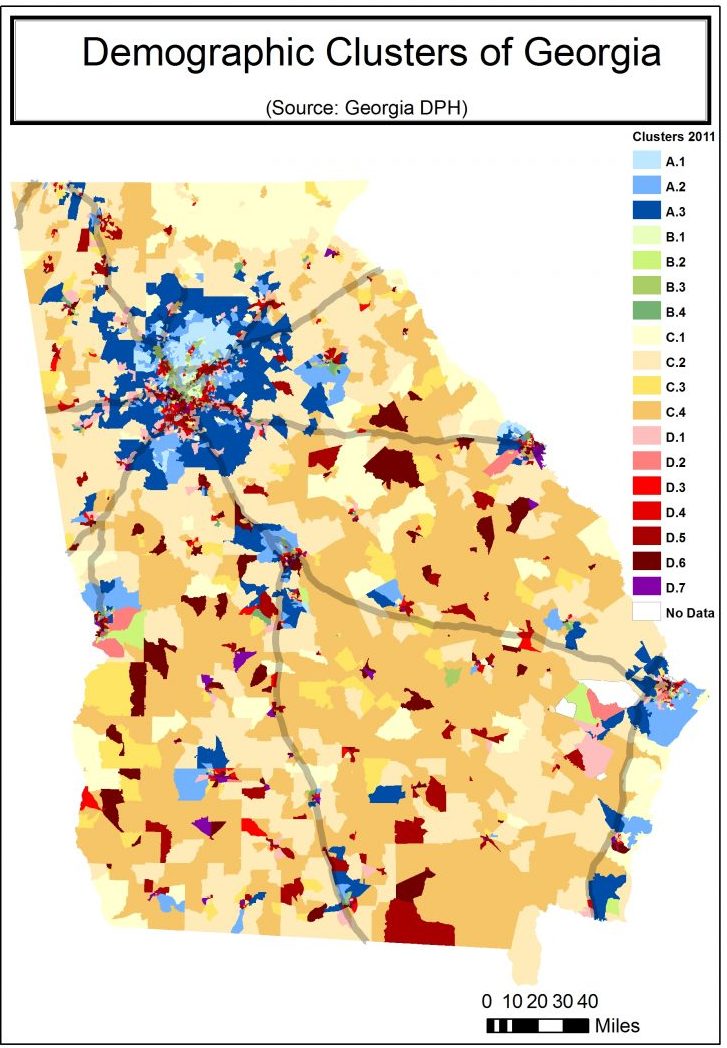

The Georgia Department of Public Health has categorized the state into 18 “clusters” based on community type and 25 sociodemographic variables. Lower numbers represent areas whose populations experience fewer health risk factors. The categories A, B, C, D refer to community type. (For instance, “C” is the umbrella category for all rural areas.) For more information about each cluster, go to bit.ly/2DBldgj. Courtesy of Michelle J.M. Rushing

Community development and housing agencies in Georgia have found themselves working with new partners: public health professionals who view affordable housing as an essential tool for improving community health.

The partnership did not arise in response to any specific housing quality issue, such as asthma triggers or toxic material. Rather, the partners were interested in taking a comprehensive look at all the ways that the location, design, and operation of affordable housing could reduce health inequities.

They anticipated that this partnership would have benefits for affordable housing developers as well. Improving resident health could improve school attendance and educational outcomes, child development measures, the percent of time adults are healthy enough to go to work, independent living measures for seniors, and mental and behavioral health status at all ages. Overall, they felt an improvement in health would likely increase family self-sufficiency while reducing many of the risk factors that lead to lease violations and vacancies.

As public health practitioners at the Georgia Health Policy Center (GHPC), a public health institute based at Georgia State University, our team initiated this relationship. We had been following the emerging research on the connections between the health status of U.S. residents and the health of the nation’s economy. On one hand, considerable evidence is available to show how people who face socioeconomic disadvantages are more likely to have negative health outcomes, such as higher levels of disability even in early childhood, more disease, and shortened life expectancy. Public health research has shown how these disparities manifest in our lungs, hearts, brains, cells, and even DNA. The result is a heavier burden of poor health, disease, mental distress, injury, developmental delay, and disability among people experiencing the greatest socioeconomic inequities.

On the other hand, there is also growing evidence of the enormous costs to households and to the economy as a whole of this additional burden of illness, disability, and death, and its associated reduction in productivity and higher medical costs. Kids who have persistent health conditions miss too many school days and fall behind, while their parents lose wages. Families exposed to traumatic experiences like community violence or eviction can develop mental health issues that make work and school more difficult. Injuries or chronic diseases that turn into disabilities limit people’s ability to work and get around. Medical costs grow, even for those with health insurance.

It can be hard to imagine reversing these downward spirals. The obvious place seems to be in clinics, hospitals, and doctor’s offices, but health care seems to account for only 10 to 20 percent of a person’s health status. Health services are also an unnecessarily expensive way to approach health problems. What about all of the investments—public and private—that we already make in real estate development, infrastructure, natural resources, and services? These investments shape the way that people live, where they live, and the environments to which they are exposed. What if we just try to make these investments in ways that expand access to health and opportunity for all? This approach is described as “health in all policies.”

Partnering for Health

GHPC was exploring opportunities for this type of intervention when a community development colleague asked if we were familiar with the “qualified allocation plan” (QAP), a set of criteria used by states to select who receives low-income housing tax credit distributions.

Here’s how it works: Each year the IRS allocates housing tax credits to state housing finance agencies, which then award the credits to developers of qualified projects—new construction or significant renovation of residential communities that provide homes for low-income households. The state agency must develop an allocation plan—the QAP—for disbursing the credits. A QAP is the federally mandated process through which states issue Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC). The state of Georgia allocates about $22 million in support of affordable housing development through this process each year. Applicants must meet certain thresholds and are then awarded points based on annually updated competitive scoring criteria.

As public health specialists, we had never heard of this policy before. However, our team had been engaged in cross-sector work for many years and had previously worked with the Georgia Department of Community Affairs (DCA), managers of the QAP. Such relationships seem to be necessary in nearly all collaborations.

So, we took a deep breath and just called the people we knew in the housing finance division. We asked if they would be interested in letting us use a policy analysis tool known as a “health impact assessment,” or HIA, to recommend changes in the way housing tax credits were allocated in Georgia to improve public health. The answer, at each level of the division, was “Yes, we’re very interested in new ways to measure our impact on health!”

Integrating Health into Practice

An HIA is a process for ensuring that plans and policies support healthy communities. The assessment is used to enhance policies in non-health sectors, such as transportation infrastructure, land-use planning, tax policy, and now community development. It is intended to be a collaborative, stakeholder-informed process. It seeks to disrupt practice in other sectors in a positive way so that central objectives—economic growth, mobility, etc.—are realized, while also mitigating potential negative health impacts and equitably maximizing potential health benefits.

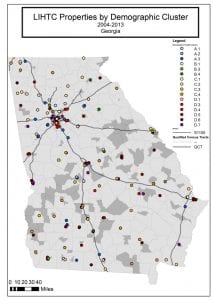

Low Income House Tax Credit properties by demographic cluster in Georgia from 2004 to 2013. Courtesy of Michelle J.M. Rushing

Affordable housing improves health in many ways, including:

- Protecting families from the environmental and safety hazards of substandard housing, such as mold, fire hazards, lack of heat, or pest infestation problems.

- Making it possible for very low-income children to live in neighborhoods with good schools and well-maintained parks.

- Freeing up household budgets so families can afford medical care and nutritious food.

The first phase of an HIA, the screening phase, determines whether a proposal is likely to have health effects and whether an HIA will provide useful information. Through tax credits, DCA is creating around 2,500 new housing units each year. The scale of the LIHTC program and its focus on lower-income populations indicate that it likely influences health outcomes as well—especially for populations considered most vulnerable to poor health.

In affordable housing policy, a primary consideration is to control costs and improve returns so that the industry can continue building or preserving as many units as possible. An HIA of an affordable housing policy would recognize that, but also ask if we could build and operate healthier properties at the same cost. Would having healthier residents in healthier communities produce any savings?

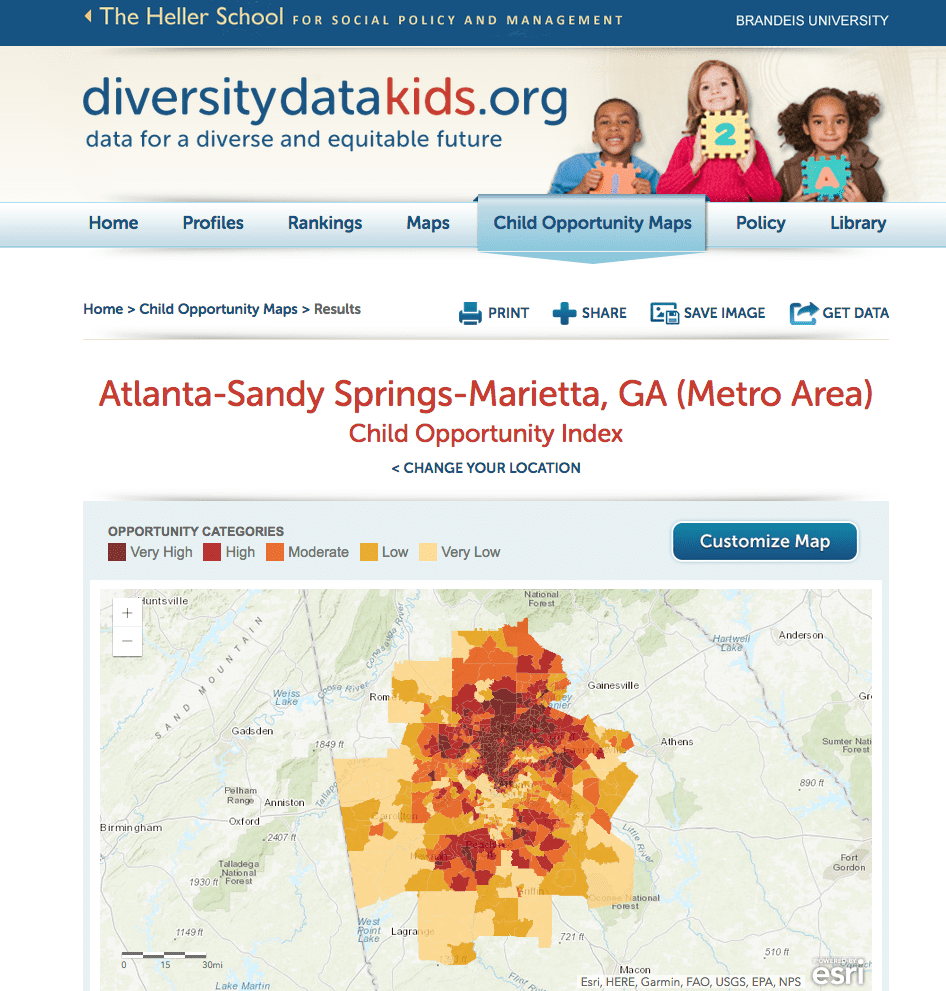

Answering these questions took the remainder of the HIA process. Due to the wide variety of tax-credit developments, the limited amount of data on the people who live in them, and the vast body of health and housing research that might be part of the answer, we had to have a thorough second phase—the scoping phase—to establish the range of health effects to be included in the HIA, the populations affected, the sources of data, and the methods to be used for assessment. Ultimately, the HIA primarily explored ways to connect low-income residents with communities of opportunity and with better educational resources, and developed a list of basic design and operations best practices.

After scoping comes the assessment phase, a two-step process that first describes the baseline health status in the population of concern, and then characterizes potential impacts of the policy on the health of that population, and the distribution of effects within the population. These potential impacts will inform recommendations for how to adjust the policy. We considered the location of LIHTC properties funded in prior years, how those locations may have influenced education and community connections, and alternative location and design scenarios.

What We Learned: Connecting to Opportunity

Neighborhood social, demographic, and economic characteristics have significant influence on health outcomes, especially for young children. Despite the introduction of criteria for deconcentrating poverty and revitalizing neighborhoods in previous years, properties were still clustered in areas with limited opportunities. Of the nearly 8,300 family housing units developed with LIHTC funding over the past decade, 70 percent have been built in areas the Georgia Department of Public Health (GDPH) identifies as having the lowest socioeconomic status and some of the highest rates of premature death in the state.

Affordable housing investments were found to improve health and quality of life, and increase opportunity for Georgia residents.

Poverty measures only one dynamic of sociodemographic status. The QAP could directly incentivize use of the GDPH Demographic Clusters, which are derived from a set of 25 indicators and linked to health risk factors such as income, family structure, and educational attainment. For instance, the A.3 cluster (diverse college-educated families in urban and suburban neighborhoods earning above median income) has a premature mortality rate that is less than half of the D.6 cluster (minority families and seniors with high school education or less working in low-paying service jobs). Yet, under past scoring, 27 percent of family developments had been built in D.6 areas compared to 5 percent in the A.3 areas. In other states, housing finance agencies can engage the state health department to find out how they identify areas with high levels of health inequities, or use national data sets such as 500 Cities, Opportunity360, or CHNA.org.

Having more affordable housing developments located in areas identified as lower-risk demographic clusters would save the lives of up to 200 LIHTC residents each year.

Access to Quality Education

Educational attainment is one of the most critical determinants of lifelong health status. School quality is a major determinant of educational outcomes, and the quality of early learning experiences proves to be a significant predictor of future success and health. On average, elementary schools near LIHTC properties scored significantly lower on the College and Career Ready Performance Index—a measure of school quality developed by the Georgia Department of Education— than schools in other areas, even though research shows that the presence of tax credit properties do not affect school performance.

DCA introduced a new scoring category in the 2014 QAP that focused on encouraging development near higher-performing schools, but it was based only on test scores, difficult to use, and few applicants claimed it. The Georgia Department of Education’s College and Career Ready Performance Index would be a better metric for school quality. It would be much easier for applicants to score, and provides a much more comprehensive measurement of school performance and improvement over time, as well as of success at addressing achievement gaps.

Additionally, points could be available for quality-rated child care sites, state funded Pre-K centers, and school turnaround plans for underperforming K-12 schools.

Location, Design, and Management Best Practices

In addition to the opportunity and education sections, we made 36 recommendations for adjustments to the QAP that would potentially improve health, specifically in the areas of active living, healthy eating, air quality, and injury risk. Recommendations included:

- Better guidance for walkability, or pedestrian circulation, on sites and connecting to the surrounding neighborhood.

- Expanded options for meeting residential service requirements to include on-site health promotion and maintenance programming, such as classes on nutrition and healthy cooking, asthma management, smoking cessation, and various types of exercise and personal fitness.

- Reducing potential exposure to asthma triggers by allowing hard flooring in some bedrooms and discouraging sites too close to high-traffic roads.

Throughout the process, we worked closely with DCA and members of the steering committee to develop changes that would benefit all interests. Some of those recommendations made it into the official Draft 2015 QAP, which allowed developers and other housing professionals to comment on ways in which proposed changes would affect their applications. The HIA monitoring and evaluation phase examines the process and short-term impacts of the HIA on decision making and supports a strategy to follow changes in health determinants and outcomes over time.

Change Is a Constant

The school quality criteria list using the College and Career Ready Performance Index standard was included in the Draft 2015 QAP. It received positive feedback for relevance and ease of use. On the other hand, a complementary scoring component that would have penalized applicants for locating their development in the lowest-scoring school attendance zones was removed, due to the number of phased developments (even senior properties) that it would have affected.

Additionally, around one-third of the 36 best practices were adopted into the Draft 2015 QAP, with all but two being retained in the final policy after public comment, and others eventually merging into supporting documentation.

This was a collaborative process in which developers helped to troubleshoot certain practices. Notable changes included a new category of eligible services that included health programs, an extra point for walkable locations, and a health innovation bonus.

The partnership did not end there. The following year, more changes were adopted. With enough time to review the health department’s demographic clusters, DCA was able to add them as an alternative to poverty rates. The new criteria appeared in the Draft 2016 QAP, along with expanded revitalization criteria. Additionally, there were multipliers in each category to incentivize development in areas of opportunity or impending revitalization, especially ones with mixed-income development, high-amenity areas, or key investments. Health and housing innovation was further encouraged.

Many stakeholders, including developers and the DCA, were curious how some of the changes would play out. Would just building near a good school really generate measurable improvements in health? So at the end of 2015, GDPH used some of its HIA funding to assess three sites that had received points on some of the health promoting criteria, and hired GHPC to conduct the project. The sites were new-construction tax credit developments, and we reviewed site-specific health needs from local and national public data sources, such as community health needs assessments, County Health Rankings, and the GDPH Demographic Clusters. We were looking to see if there were things that could be added to the criteria that had been overlooked, and to see if developers had to risk compliance with other tax-credit standards to build healthy. Would there, for example, be conflicts between the pedestrian circulation guidelines and their standard building plans? Did developers need more guidance after they had agreed to offer unspecified “healthy services”?

We identified more specific interventions for each property. The recommended interventions, which were completed in 2016, included services to promote healthy behavior or improve access to health care, a community garden, better playground and pedestrian walkway siting, and partnerships with local organizations that promote health and wellness.

In 2016 DCA added a set of healthy housing initiative criteria to the 2017 QAP, which awarded points for coordinated on-site amenities and services that would provide health care screening and services, and promote healthy eating or physical activity. GHPC provided comments on this section, and in 2017 worked with applicants to help them interpret the documentation for the points. In addition to providing the healthy amenity and service, applicants were expected to review local health indicators to select from the three approaches, and to provide some annual evaluation for the first five years. We found that most applicants were unfamiliar with the health data sources, and needed some support to connect with the right health partners. Although nearly everyone involved in affordable housing production intuited their ability to support healthy living for their communities, they were sometimes surprised by the way that specific determinants of health could be affected through design or operations.

In 2017 a new partnership evolved. With the support of the Kresge Foundation, DCA brought on GHPC and Southface, a sustainable development expert, to integrate green and healthy design and services into eight public housing properties being rehabilitated through the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program using 4 percent housing tax credits. Housing agencies, developers, architects, property managers, and residents will learn how to create healthy communities. An evaluation phase lasting through 2022 will look for measurable changes in behavior, access, health status, medical expenses, and residents’ burden of unhealthy days that affect their ability to engage in education or employment.

Any one of these changes would likely lead to improvements in health outcomes and behaviors. Employing a holistic perspective that considers all of these interventions together—each of which makes some contribution to health and quality of life—would be most likely to fully achieve the potential for affordable housing investments to improve health. A fully funded affordable housing program that is tuned to reduce injury and illness could improve wellbeing, increase productivity, and reduce health care costs in Georgia. We’ll be there to provide the proof when it does.

Comments