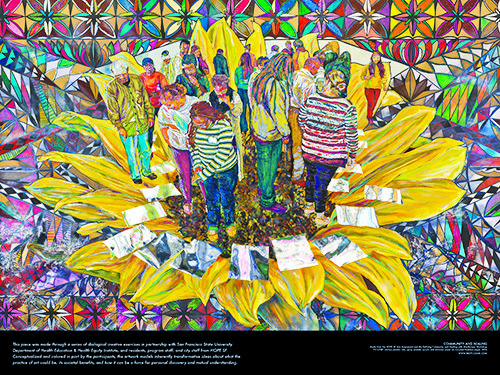

An image created as part of the community engaged art work of residents, HOPE SF leaders, and San Francisco State University students.

What does it mean to value a public housing community that has been neglected for decades and now experiences high rates of violence, degraded housing, limited infrastructure, and a frayed social fabric? For many developers, city officials, and others, it means tearing all that down and replacing it with new mixed-income housing. What this redevelopment method often overlooks, however, is the experience of residents who bear witness to the physical destruction of their homes and the elimination of familiar street corners, basketball courts, green space, and all the other private and public signposts of community and lived history.

Simply inviting residents to participate in design charrettes and an official community planning process does not mitigate the significant loss of home that reverberates across generations. Just the inherent language of community “transformation” signals that what has come before is not worth holding on to, and renders the history of these public housing sites insignificant. Knowing this, our challenge is not to envision “transformed” communities, but an evolution that carries with it visible markers of what has come before and illuminates the history of the place and the people who have lived in these places for decades. What is needed is a radical act of longevity.

In San Francisco, a far-reaching process is taking place to replace and rehabilitate thousands of units of public housing. Called the HOPE SF initiative, four of the largest and most debilitated public housing communities will be entirely rebuilt, including new streets, parks, bus stops, community spaces, and housing. The intent is to keep residents in place and living in their communities without moving them out of San Francisco, never to return. Even with this commitment and the promise of safer, healthier housing, honoring community history has taken on increasing importance as residents have voiced their grief as the place they have called home is entirely demolished. “Once they tear it down, you’re tearing down the history of what makes Potrero Hill. Whether you call us a ghetto or a project … there’s a lot of history here and a lot of stuff has happened here.” Furthermore, community residents believe that historical recognition is needed to solidify their sense of belonging in the newly developed mixed-income housing that will be created through the HOPE SF initiative.

In response, HOPE SF has partnered with San Francisco State University (SFSU) to see how art can play a role in visually and experientially carrying forward individual and community history, culture, and connections as part of this neighborhood change effort.

As a first step, an assessment was conducted collaboratively by SFSU Master of Public Health students and HOPE SF leaders to understand community views on art as a vehicle for healing and community building. Community residents, local program staff and policy makers shared their thoughts on how art could promote the well being of residents, as community change efforts forever alter the physical and social landscape of the HOPE SF communities. Through this assessment, we found direction for a vision of community “longevity” instead of the oversimplified notion of community “transformation,” and the role art and artists can play in realizing this vision.

Promote community artists and their work to reflect and celebrate residents, history, and place.

In all the HOPE SF sites, there are residents who are also artists—painters, DJs, musicians, poets, sculptors, dancers, chefs, photographers, and more. These individuals and a few homegrown arts organizations are mostly unfunded and unrecognized. There is a significant opportunity in the community change process to intentionally promote and engage the leadership of these community cultural stewards. Their involvement in the design process and the creation of works of art that reflect community history and culture can be instrumental in establishing visual and experiential community longevity. Making room for community artists alongside outside architects, designers, and developers is not necessarily easy, as engaging them as partners or even leaders requires an aesthetic and process reprioritization. Just as there is a call for local hiring for construction, support of community artists as part of a redevelopment process should be required. Instead of erasing public housing residents and their history in the process of creating a mixed-income community, it calls for a celebration and centering of their experience. Community artists can reflect, promote, and make this history visible.

Foster community healing by honoring the personal and community transformation through community engaged art processes.

In today’s public housing redevelopment process, there is an emphasis on the smooth transition of residents into the new housing. However, the reality for many residents and staff is a wrenching, drawn-out process that can be filled with doubt, excitement, worry, and anticipation all against a backdrop of the regular daily opportunities and challenges of life. HOPE SF residents see the process of creating art as way to cope with this stress. “I would say that it’s an outlet. It’s calming for me … art has been a whole transformation to help me be able to live in this community, survive in this community, and continue to work hard in this community.” In addition to the individual experience of making art, community engaged art processes that make visible the physical and emotional experience of residents during this time can help to heal collective wounds. Marking the emotional journey experienced by residents and staff, and acknowledging that what is being left behind or destroyed was needed to make way for what is new can also be healing.

Illuminate community history through permanent public art.

Creating permanent public art that reflects the history of public housing and its residents is essential to community longevity. Visioning processes that ask residents to imagine a “new” or transformed community have the potential to devalue history. Instead, we should be asking questions early in the design process about what residents want to remember about their community, and what is important to share with future residents. Capturing these intentions in permanent displays of creative expression are essential to a linking of past and future. In one HOPE SF site, a project titled “Generations” is gathering the stories of community elders and creating permanent public art that makes their experiences visible in the new mixed-income community.

The evolved idea of “placekeeping” infers that in addition to brick and mortar spaces, there are cultural memories and practices associated with a locale. When new buildings change a neighborhood’s aesthetics, its values continue through the residents. Artists document and present culture in content and form, helping to ensure that a community’s future will be visually and emotionally linked to its past.

Comments