Photo by Flickr user Jason Tester Guerilla Futures, CC BY-ND 2.0

In Miriam Axel-Lute’s recent post here, “Place Matters But Place Changes,” she references “a study done by Governing magazine that found a 20 percent gentrification rate for census tracts in the past decade in the largest 50 cities in the country, a greatly accelerated rate from the previous decade.” She goes on to note that, while an increase over past rates of gentrification, a 20 percent gentrification rate still means that 4 of 5 low-income neighborhoods are not gentrifying.

These are basic, straightforward conclusions to draw from the Governing study. However, there are a few huge, interrelated problems with the underlying study in being able to adequately describe our current round of gentrification.

The Current Round of Gentrification Is Driven by Rental Housing

The Governing study, and most quantitative studies of gentrification, use rising home prices as the primary indicator of gentrification. This is fairly standard practice and therefore not a problem unique to the Governing study. But the current round of gentrification is driven by the rental housing market, not the homeownership market.

The Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University’s “The State of the Nation’s Housing 2015” report talks about the current decade as being “on track to be the strongest decade for renter growth in history.” The foreclosure crisis turned many homeowners into renters and made buying a home more difficult, and the share of people looking to rent housing is at a 20-year high. Rental housing construction, while strong, is not keeping up with demand, and new units are primarily being constructed for the high end of the market. Vacancy rates are down for all segments of the rental housing market, but especially for units renting at $800 or less per month. And, per the JCHS, “falling vacancy rates have lifted rents, improving the financial performance of rental properties, but straining the budgets of millions of households unable to find units they can afford.”

So, to be relevant, metrics of gentrification (at least for the current round of gentrification) need to reflect changes in the rental market.

Gentrification Is Happening Faster Than our Ability to Track It With Census Data

Not that I want to call out the study authors, per se, as this is not so much a problem of their analysis but with the limitations of the data (and about how we understand/talk about recently released studies which are based on old data). The study shows 1 in 5 low-income census tracts gentrifying in 2013 (actually it’s worse than that—the Governing study uses five-year ACS data, which means the numbers skew slightly more toward 2009 through 2013–an appropriate data set to use when conducting census tract-level analysis but not the best for measuring for trends that happen quickly. My ears-to-the-ground, anecdotal sense is that gentrification and displacement have intensified over the past year, even over the past several months, such that 2013 is a more accurate starting point to measure the current round of gentrification, not the ending point. The authors used the most recent data available from a reputable, public source–if I had designed the Governing study, I don’t know if I would have done it much differently. But the study doesn’t represent what is happening in low-income neighborhoods right now. And we shouldn’t mistake it for such.

RELATED ARTICLE: What Does “Gentrification” Really Mean?

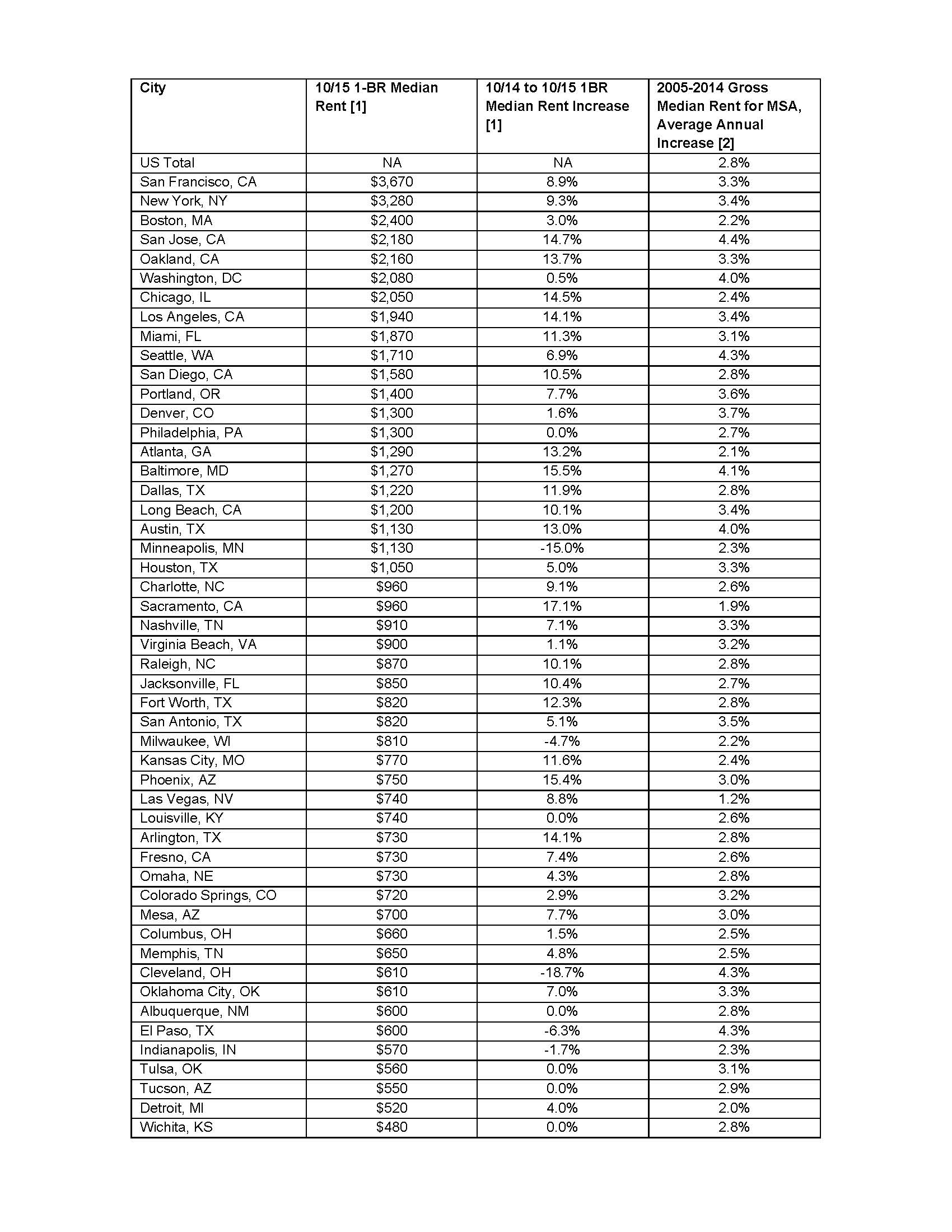

And the past year has been a doozy in terms of rising rents. Looking at rental data from proprietary websites, which scour online rental listings to calculate regional rental rates, has its own methodological questions, but at least provides us with more up-to-the-month data. And this more recent data is dramatic. For example, over the time period October 2014 to October 2015, Zumper.com shows double digit percentage increases in median rents for 18 of the 50 cities that it tracks, with several more cities showing annual increases on the order of 9 percent. In contrast, from 2005 to 2014, the average annual increase in U.S. median rent was on the order of 3 percent per year. Per the table below, recent and dramatic run-ups in rents look to be widespread–in far many more places than as indicated by the Governing study.

Sources: [1] = https://www.zumper.com/blog/uploads/2015/11/November-2015-Rent-Report1.pdf; [2] = 2005 to 2014 1-year American Community Survey

The above chart is not straight apples to apples, but it at least shows that something more is happening than what can be seen within the Governing study time period–a real reason why right now, gentrification is, as Miriam says, “on everyone’s tongue… from Sacramento to Nashville to Lexington…”

Gentrification Isn’t Only a Problem for Low-Income Neighborhoods

This point probably deserves a blog post in and of itself. In looking for gentrification, the Governing study authors define a baseline universe of census tracts that were eligible for being gentrified. Per their definition, all of these census tracts were low-income in 2000. That is, in seeking to define gentrification rates, the study tracks only low-income neighborhoods (or more precisely, neighborhoods that were low-income in 2000). As an example, the city of San Francisco has 196 census tracts of which only 16 were “eligible to gentrify” per the Governing study, and thus only 3 of these 16 showed evidence of gentrification. (A side observation here is that San Francisco was already so gentrified in 2000 that less than 10 percent of its neighborhoods were low-income in the context of the five-county San Francisco MSA!) The point here is that gentrification doesn’t only happen to low-income neighborhoods–it is also a problem in its impact on middle-income and mixed-income neighborhoods.

If we are focused on the impact of gentrification on low-income people, we should be concerned about gentrification in all neighborhoods. A typical census tract may have anywhere from 1,000 to 3,000 housing units. In most places, but especially in dense urban settings, a neighborhood of 1,000 to 3,000 housing units will contain many units that are above and below whatever the median home price or monthly rent is; this is the very definition of “median.” In gentrifying places, there is not only upward price pressure on all housing units, but particular pressure on the segments of the market that were “informally” affordable housing (i.e., cheaper housing but not formally covenanted as affordable), as whole buildings, for example, are flipped (emptied, fixed-up then re-marketed) to target a higher market segment. The median moves up as all prices rise–but also as the cheaper options disappear. Part of gentrification is that mixed-income places–regardless of whether the neighborhood started as a low-income neighborhood–become less mixed-income as low-income people are priced out.

Gentrification, therefore, is not just about what happens to low-income neighborhoods. It is the story of the loss of mixed-income neighborhoods, a phenomenon not completely registered within the Governing study. If we listen to Raj Chetty about mixed-income places producing greater economic mobility for low-income people, we should all care about the loss of these mixed-income neighborhoods too.

We need better measures of gentrification. Metrics that track rental data, that are more current, and that recognize that gentrification affects more than low-income neighborhoods. If we had such metrics, I think a much more widespread and insidious problem would be much more visible.

It seems to me that this post confuses rent increases with gentrification. But where rent is rising throughout a region (as has been the case in most of the United States since 2008), rent increases can occur even if a neighborhood’s demography is unchanged. To describe that as “gentrification” is really a radical redefinition of the term.

Yes. I don’t mean to say that rising rents in and of themselves = gentrification and I agree that gentrification needs an accompanying change in demographics.

But, rising rents are a flag that something is happening. And extreme and recent increases in median rents (like we are seeing now) are an indicator that gentrification is likely more widespread than can be seen with the current metrics in question.

I don’t mean the data that I present to be the new metrics (or even the basis for the new metrics — given the methodological problems of basing current rent data from online listings). Only to use the data to call to question the current metric.

Well, rising rents are certainly an indication of pressure on the existing residents. Given that most renter households’ dollar incomes aren’t going up as fast as rents, the households either have to move or pay more of their income for rent. Both trends—neither desirable—are presumably happening, the question is on what scale. If you can identify where rents are rising, you know places to look for gentrification.

I think that might be true at a time or place where rents are stable. But at a time where rents are rising everywhere, or at least everywhere in a certain city, I don’t think so.

It seems to me that over the past few years the latter has been the case, as tightened lending standards and the recession have driven people out of the market for buying housing) I don’t think that is the case.

Pardon my ignorance. How does the push for inclusionary housing and the push to mix low income families with higher income families for better exposure and benefits fit with higher rents. It seems like that would affect the census (or ACS) data when those fully come to fruition. The average rent would for a block group or census tract would go up.

Also, what is the impact of the “boomers” retiring and downsizing and even choosing to rent vs. own?

Gentrification conversations are very important in ‘hot’ markets, but can be used inappropriately in ‘cold’ markets. Where values are severely depressed, rising values aid existing underwater owners and provide a market in which both investors and owners can afford to make improvements on properties. Similarly, where rents are too low, empty multifamily units sit and rot. Let us not throw the baby out with the bathwater.

I had the same thought as ML: I find it highly suspect that you would make such a strong connection between rising rents in an entire metro area and gentrification. Yes rising rents are an important data point in determining whether gentrification is happening within a neighborhood, but metro-level data alone will never be able to capture that for you.

This is especially concerning given the amount of evidence pointing to increased income segregation, which would only serve to skew this data rather than support your claim. We cannot use these numbers to assume that rents are automatically increasing faster than average in lower-income areas.

For instance, if rents increase at a rate of 5 percent in a wealthier neighborhood and 5 percent in a neighborhood perceived to be gentrifying, can we reasonably assume that the rent increase in the lower-income area is a result of gentrification? Of course not. But that is precisely what your argument suggests.

Response to Steve Lockwood:

I agree with you that we need separate approaches to “hot” and “cold” markets. I am not advocating jettisoning cold market approaches in favor of a hot market-only approach. While I believe that we need better developed approaches for community development in hot markets, this should not come at the expense for community development in cold markets. It is about knowing the dynamics of a particular place and acting within that context.

Response to Bob J:

Inclusionary housing in a low-income neighborhood might have the overall effect of increasing median rent for the neighborhood. But I don’t think that this would necessarily be a bad result. It could be a good result, depending upon the context.

Inclusionary housing in a mid- or high-income neighborhood might have the overall effect of decreasing a neighborhood’s median rent. And this is likely a good result.

And yes, boomers retiring and downsizing and choosing to rent instead of owning is another factor putting pressure on already tight rental markets.

Response to Chris L.:

I am a little confused as to your disagreement. When you repeat back what you see as my arguments, I do not recognize them as something I’ve said. So, it’s probably something in how I’ve framed things in what was intended as a short blog post in response to a study published in Governing magazine. Let me try to clarify. And in the end, we may still disagree, but at least we can disagree on the real substance of my arguments.

My point about rising rents and gentrification is based on what you said: “rising rents are an important data point in determining whether gentrification is happening within a neighborhood…” I think this is relatively uncontroversial point. Of course median regional rents don’t say what is happening in any particular neighborhood. Of course you need data from specific neighborhoods. And the data should be about more than simple housing costs (e.g., stuff like race, education, etc.). Again, rising rents do not mean gentrification. But it is a data point. And rapidly rising rents, though not determinative in and of themselves, are a red flag.

I think you and ML are confused about what data I mean to stand for which points in my blog post. Each bolded heading marks a very specific argument that is centrally about the limitations of the study in Governing magazine. The city-wide median rental data in the big table relates back to the heading that “Gentrification is Happening Faster than Our Ability to Track it With Census Data.” The Governing study covers a time period of 2000 to 2013 (the limits of the census data at the time the study was conducted). My argument in the specific section is that housing costs in many places have increased dramatically SINCE 2013. This is not intended to stand as absolute evidence that gentrification is happening in every single place. Merely to show that “something more is happening” than can be seen in the Governing dataset — i.e., there have been major changes to the housing market in the past couple years that are not captured in their dataset. These changes have not been distributed equally all across the country and are not distributed equally in regions. And of course more specific data is necessary to show gentrification on a neighborhood by neighborhood basis. But my simple point with the big table is that gentrification data needs to be more recent than what is possible with census data.

And that if we had more recent data, we would likely see more evidence of widespread gentrification. I don’t intend that the data I present is this evidence of widespread gentrification — merely a friendly criticism of the Governing study and a point about the need for more and better metrics.

Thanks for the post focusing on renters and gentrification! It certainly supports what the Right to the City Alliance has been arguing (see their Rise of the Renter Nation report, which I helped them with). And this is Bay Area specific, but the Urban Displacement Project at UC Berkeley has some great, and recent work mapping displacement here and it may be of value beyond the Bay. They focus a lot on the rent issue specifically:

https://www.urbandisplacement.org/