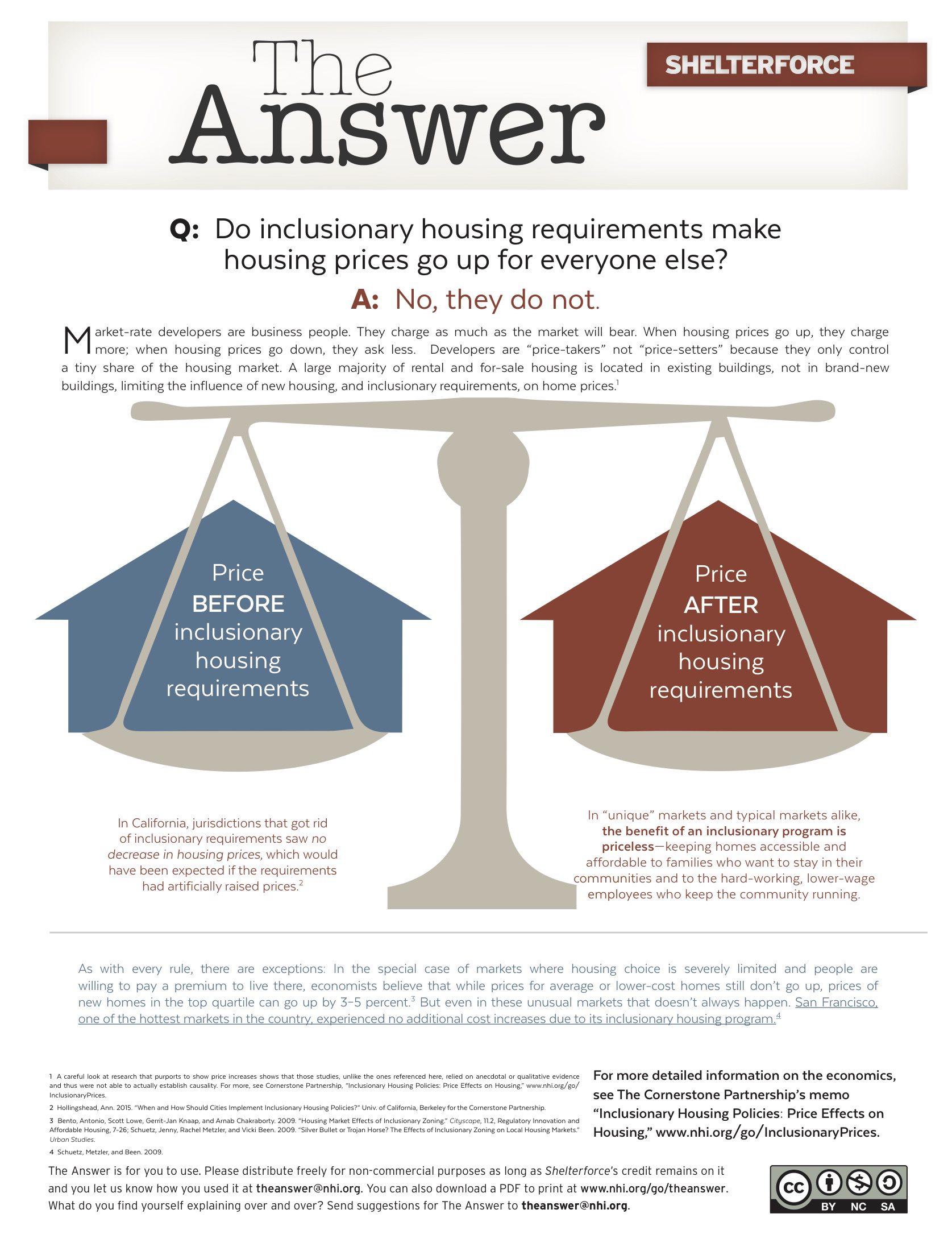

Founders and supporters of the San Francisco Community Land Trust gather to celebrate its launch. Photo courtesy of Tracy Parent

As interest in urban living increases, the cost of housing in many hot markets is skyrocketing. Activists are responding by organizing around housing equity and against displacement and are looking for effective tools to create inclusive communities. Increasingly, many of them are considering community land trusts (CLTs).

The CLT Model

CLTs are a form of permanently affordable housing in which a community-controlled organization retains ownership of the land and sells or rents the housing on that land to lower-income households. In exchange for purchasing homes at below-market prices, owners agree to resale price restrictions that keep homes permanently affordable to subsequent households with similar income levels. Meanwhile, the sellers are still able to build some equity. A CLT provides stewardship for housing on its land, such as preparing homebuyers for purchase, supporting owners through financial challenges, shepherding resales, and managing rental units. CLTs also manage non-housing uses, from urban greenhouses and gardens to commercial and office spaces.

CLTs are considered a prime tool for allowing residents to retain a stake in gentrifying areas. That’s because the initial subsidy remains with the building and keeps it continually affordable over time, without requiring new influxes of public money. CLTs have benefits in weak market areas as well. Their stewardship protects communities by ensuring fewer foreclosures, better upkeep, and stable residents. CLTs bring sustainable homeownership within the reach of more families, supporting residents who want to commit to their neighborhood long term. And they provide an avenue for a community to have a say in redevelopment plans.

New units come into a CLT in a number of ways: the community land trust may develop them, partner with a developer, convert existing houses through a buyer’s choice program, or serve as a preservation purchaser of multi-unit buildings. (A “preservation purchaser” is one who steps in when affordable units are at risk of being lost and maintains their affordability.)

Community Organizing

Traditional community organizing creates an organized base of residents who are empowered to determine for themselves what they need and then act to get it. Organizers define organizing as creating a counterbalancing weight of “organized people” to counter other forms of power, such as corporate or governmental.

Sometimes, when powerful forces are aligned in opposition, or no one is paying attention to their issues, organizers use confrontational tactics such as protest or direct action—opposing a candidate in an election or gaining media attention to highlight their cause. For more established groups, which have built enough power and cultivated enough relationships to already have a seat at the table, organizing more often means keeping a base of people informed and active, ready to turn out to public meetings or submit comments. Both kinds of organizing are usually required in cycles over the long term.

(Confusingly, sometimes some nonprofits and community groups use the term “organizing” to mean conducting general outreach and education, gathering feedback on their own work, or holding social/civic events. These things are often part of organizing, but most professional organizers would argue that by themselves they are not sufficient to count as organizing, and it’s not the definition we are concerned with in this article.)

Organizations that rely on their relationships with local government for aspects of their work, such as zoning changes and building permits, may find it particularly difficult to engage in confrontational organizing. This has been a long-standing issue in the community development world, with many observers worrying that reliance on accessing public affordable housing funds has turned community developers away from their civil rights roots and muted their voices on controversial issues in their neighborhoods and cities.

Much like community development corporations (CDCs), many CLTs grew from organizing roots, and today many more organizing groups are considering forming CLTs. How have groups that created CLTs navigated the transition from organizing around the issues that a CLT might help solve to actually running one?

We spoke with six established CLTs in different parts of the country to see how they connected organizing and community land trust activities and how their organizing efforts changed over time.

Where Did They Come From?

The organizers who formed these CLTs faced a range of different conditions.

Some started in high-vacancy neighborhoods with almost no housing market, or other distressed areas. In the mid-1980s, the Dudley area of Boston was so devastated that 21 percent of the land was completely vacant. Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative (DSNI) formed to fight the illegal dumping that had followed a wave of arson for profit. Durham CLT likewise grew out of a campaign to get resources to a neglected area suffering disinvestment in order to stabilize the neighborhood and improve the condition of the housing stock. Sawmill CLT was born when low-income residents banded together to fight a neighboring factory that was polluting their air and threatening their health.

Those starting conditions are in marked contrast to those of the San Francisco CLT, which formed in 2003 at a time when the city was already becoming one of the hottest real estate markets in the country. Low-income residents there were primarily concerned about skyrocketing rents and illegal evictions for condo conversions.

In Los Angeles and Philadelphia, organizers faced a combination of hot and cold market challenges. The groups’ target areas were suffering from vacancy, disinvestment, and poor-quality housing, and yet development pressures in surrounding areas were looming.

Despite these differences, the reasons these organizations gave for choosing to start a CLT are remarkably similar. Even those community land trusts that began under weak market conditions recognized the potential for displacement as their neighborhoods—all located in close proximity to downtowns, university districts, or other popular areas—improved. And all spoke of wanting community control of land in order to prevent residents from losing their homes or being unable to afford home purchases. Notably, all six case studies have reported rising property values since they were founded, validating their concerns about retaining affordability.

Making the Decision

“A lot of times groups want to jump into creating a CLT,” thinking it will magically solve a neighborhood’s problems, says Harry Smith, director of Dudley Neighbors Inc., the CLT that DSNI formed in Boston. “But first we say: ‘Do you have a written down vision of development in your community, and can you say how a CLT fits into that?’”

Three of the groups we spoke with carried out extensive conversations with their community members before moving forward with the model, making sure there was agreement that it was a good tool for furthering their vision.

In Philadelphia, the Women’s Community Revitalization Project (WCRP), in conjunction with a coalition of local civic organizations, held dozens of public meetings, bringing in CLT experts like John Davis of Burlington Associates. At a final key meeting, a pastor and an actor conducted role-play exercises to help the more than 75 community members who attended understand what forming a CLT would mean and to explore their concerns about resale restrictions. Attendees voted by sticking their name tags along a continuum from “very happy” to “not at all happy” with the idea. Only when the votes showed that the community was on board did WCRP move forward with the CLT.

In Boston, the city was circulating a proposed master plan for the Dudley area that had no resident input. DSNI’s response was to look for ways to have a voice in decisions regarding land use, culminating in the rallying cry “Take a stand, own the land.” DSNI helped the community consider many different models and a CLT was chosen as the best fit for its members’ carefully crafted community vision.

In the Sawmill area, the community was worried about getting another industrial neighbor. Executive director Wade Patterson recounts, “So the conversation changed to how to get control over the land.” After leaders attended a conference to learn more about CLTs, they held a series of community meetings where residents aired concerns about not owning their own land under the CLT model. Patterson says a turning point involved a community elder standing up and saying, “You think you own your land now? Stop paying your property taxes and see what happens.”

What’s the CLT’s Role in the Community Vision?

Despite the similarities in goals and visions, these six CLTs took different approaches to their organizational structure and role. Each CLT was broadly envisioned in one of two ways: (1) As an entity that would implement the community’s vision using the CLT model, or (2) as a more narrowly focused technical organization that other organizations implementing a community vision could turn to for help with CLT-specific functions.

Durham and Sawmill CLTs were both created by grassroots, neighborhood-based organizing groups to be organizations that would implement the community’s vision. “They wanted some power, then realized housing could be the answer,” says Patterson of Sawmill CLT. “The intention was to have some entity with more clout.” Durham and Sawmill CLTs are both stand-alone organizations that carry out housing development themselves, with most of their staff devoted to development, stewardship, and property management.

The San Francisco CLT, Dudley Neighbors Inc., and Community Justice CLT in Philadelphia were not created to be organizations that would themselves take on the mission of implementing a community vision. Other organizations were taking the lead on that work. Rather, these CLTs were developed as tools for those existing organizations to use in fulfilling the permanently affordable housing and community control of land portions of their vision. This was accomplished in different structures for each.

The Community Justice CLT is a program of WCRP, which already had both in-house development and organizing expertise. Dudley Neighbors Inc. (DNI) is an independent CLT organization, but one that is very closely tied to its parent, DSNI; DSNI appoints a majority of DNI’s board and the two organizations share staff. SFCLT is a stand-alone organization that retains a close relationship with the various housing organizers that collectively founded it. It focuses on implementing a particular piece of the vision being pursued by its founders—buying small apartment buildings and converting them to co-ops on CLT-owned land.

T.R.U.S.T. South LA somewhat defies these two categories. While it seems to have been envisioned as a tool by its three founding partners—Esperanza Community Housing Corporation, Strategic Actions of a Just Economy, and Abode Communities—it has since taken a broader role in implementing a community vision. “Originally we formed as a land acquisition group; then our members wanted to organize,” says executive director Sandra McNeill. The group now describes itself on its website as “a community-based initiative to stabilize the neighborhoods south of downtown Los Angeles.” T.R.U.S.T. South LA is a standalone organization.

Effects on Organizing

What does it look like for organizing when a CLT is both the lead entity for implementing the community vision and the developer? Sawmill and Durham both do some organizing and understand its importance. “Organizing needs to precede development, whatever you can do to strengthen organizations in the community,” says Durham executive director Selina Mack. “We see government making decisions about what a neighborhood needs so often, then moving in and doing it. We should involve the community as much as possible.” Both actively support neighborhood associations and the kind of public engagement and participation they require, from gathering neighbors to ask questions after a shooting to supporting a city council ordinance addressing a traffic problem in their neighborhood. Durham is also mobilizing its membership as part of a coalition to rally support for creating more affordable housing near expanding transit.

But for these groups, organizing can also take a back seat to managing the demands of providing community-controlled affordable housing in a changing neighborhood. “We’ve gone from organizing to creating change in the neighborhood,” says Mack. When the group formed almost two decades ago, “we were confrontational, marching in the streets [and] demanding money and attention from City Hall. . . . We’ve been there and done that. There isn’t a need for that today; the neighborhood has improved dramatically.” Also, the funding for Durham’s one staff line for community organizing was cut in 2002, something that is perhaps more likely when such a position is not considered essential for the organization’s survival.

The Sawmill area neighborhood associations, including the Sawmill Advisory Council, which originally launched the CLT, focus on “community building by hosting holiday events, etc.” says Patterson, but sometimes they take “confrontational stances on issues, [and] we’re there to lend support.” Sawmill CLT largely provides logistical support, he says, such as meeting space, but is not out front.

Of the CLTs that were envisioned more as tools, organizing has been continued by the founding groups. WCRP, which strongly prioritizes its organizing work, continues to maintain an entire department devoted to organizing. DSNI continues to make organizing and community planning its number one priority. (Because of its long history and set of relationships, it also engages less in confrontational organizing than it once did, but doesn’t shy away from it when needed.) SFCLT is membership-based and organizes its members to support issues that its coalition partners are pushing for, but it doesn’t “initiate organizing” on issues, according to director Tracy Parent. T.R.U.S.T. South LA does a lot of organizing, though nearly all of its policy work is conducted in coalition with other groups, including its founding partners.

Whenever organizing and development overlap, there can be tensions, which is part of why organizing often falls away as a group moves into development work. “My experience is that affordable housing developers generally aren’t risk takers,” says LA’s McNeill. “They may be involved in political work to ensure the funding streams are in place for affordable housing, but that’s as far as most of them go.”

Those rare CDCs that have continued to balance organizing and development have all made explicit commitments in mission and staff time to continue their organizing work and accepted the risks of sometimes “biting the hand that feeds them.” It’s the same for groups with CLTs. DSNI is “part of coalitions and movements doing direct pressure on different policy or development issues,” says DNI’s Smith. “We ride that line like everyone else, and strategize as we go, but organizing trumps our development agenda.”

“Sometimes you lose relationships when you’re organizing,” says Nora Lichtash of WCRP. “At times we need to target you if you’re not doing the right thing, to build power and respect for our work. . . . Sometimes people don’t like to be pushed to do the right thing.” For example, WCRP has pushed the council person who represents its neighborhood hard enough on certain issues that she declined to give the CLT vacant land it had been hoping to secure for its first development. (In the end, however, the council person did help the group establish a citywide land bank, which furthers some of the same goals as the land trust.)

Lichtash says that while it can create tensions, she feels organizing and CLT functions should stay closely related anyway. “It’s important to remember that organizing and doing CLT work and building affordable housing fit together,” she says. “Your funders think you should be doing one or the other, but . . . it’s not good for CLTs to be separated from organizing. . . . You’re building your capacity, not just to do your present work, but for future work. . . . When you organize, you’re respected because you have people power.”

In fact, having a CLT while continuing to make organizing a priority can be a unique strength. “Having a land trust gives us an extra level of impact” when DSNI organizes around the fate of a particular parcel of land, says Smith. “If we didn’t have the land trust model, they’d say that someone else should own the land. But we make no bones about it. We should own this.”

Who Wears the Hard Hat?

Development is a complicated and expensive business. So the question of whether either a fledging, independent CLT, or an organization with no development experience starting a CLT should become a developer is a big consideration—even for those groups that are confident in their commitment to organizing and comfortable balancing the two roles.

Several leaders of these groups argue that when the capacity already exists locally in other organizations, adding development work to a new organization is likely to be a net loss and detrimental to a group’s organizing and vision implementation work.

Neither DSNI nor DNI carry out development directly; DNI partners with existing developers. SFCLT has in-house real estate expertise, though it doesn’t develop new buildings. T.R.U.S.T. South LA considers itself part of the development team on its housing projects, but always partners with existing developers to accomplish actual purchase, financing, and construction or rehab.

DSNI did step in as the developer on DNI’s very first project after the original developer backed out, and it was “traumatic” for staff and board, says Smith. “It took so much time. It distracted DSNI from its core functions. It’s important to be explicit: If you do development work, it will take away time from organizing.” The reason that’s bad, he adds, is that organizing is cumulative. It takes years, and “a lot of sacrifice . . . to form a truly representative, neighborhood-based organization. If you cut corners, you can risk jeopardizing a lot of power you’ve built up over the years.”

The prospect of controlling development resources and accessing developer fees can be understandably seductive to grassroots groups, says Lichtash. But they should proceed with extreme caution. “If you’re trying to talk about becoming a developer, it can muddy the waters,” she says. “You have to focus on every detail in million dollar deals. It really takes you away from the educational work you want to do. Real estate work is very hard, speculative. You think you’re getting one thing and instead you get another. When we first started people told us that, but we didn’t believe them. I now tell people to partner for a long time first. It’s hard /to keep tenants happy and funding sources happy.”

Patterson of Sawmill agrees. “I’m always shocked by the amount of administrative overhead that’s required.” And Patterson says that if you can’t make the numbers work, “it’s important to know you can pull out of a project if needed. We’ve come close.”

T.R.U.S.T. South LA’s McNeill says, “Development definitely has its own language. It’s complex stuff. Nonprofits who do it have large budgets and tend to have sizable staffs. I respect the skill it takes to pull off these deals; it’s a very different skill set from what we do.”

Another consideration is that in the current funding environment, many of the sources of subsidy that CLTs have traditionally used to develop and steward their units are being slashed, and mortgages for potential CLT homebuyers are harder to find. Affordable housing development is not an easy industry to break into these days, says McNeill: “We’ve gone through enormous shifts in the housing industry. The reality is there’s not an opening now for new organizations to get into the development business. It’s definitely not the time.”

Likewise, even the ongoing stewardship work of a CLT requires a different kind of relationship with residents than that of an organizing group. “Developer’s fees and rent collection could impact the relationship with residents and the power dynamic,” says Smith of DNI. “You’re responsible to leaseholders and non-leaseholders in your community, so there are tensions,” says Lichtash of WCRP. “Organizers often paint issues as black and white, as clear moral choices, but there are nuances,” when you are involved as property manager, says Parent of SFCLT.

Eyes on the Prize

A CLT is, in many ways, a perfect tool for addressing many of the concerns and goals of today’s housing activists. But organizing groups interested in supporting the CLT model should be aware of the different dynamics—including the substantial amount of work and risk to their core mission—that come with becoming a land owner, steward of affordable units, and property developer or manager.

Once a community has determined that a CLT is an appropriate tool to help it fulfill its vision, the next question should be: How will the roles be divided up? Who is taking the lead on implementing that vision? Is there an organization already in place that’s committed and able to take that on, as was the case with WCRP and DSNI, or does one need to be created? Are there groups serving the community that already have development expertise and access to funding that would be philosophically on board with partnering with a CLT or even folding one into their work? How could the new CLT partner with and support the community’s organizing work rather than distract from it?

Many newer CLTs are following the lead of groups like DSNI and T.R.U.S.T. South LA by setting up a separate organization to manage the stewardship and land ownership functions of a CLT and then drawing on the capacity of existing developers through partnerships. While every locality is different, this seems like a wise place to start—especially for those groups that want to preserve their energy for the important work they started with: organizing.

A version of this article first appeared in LandLines, July 2015.

Comments