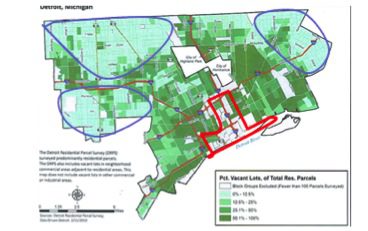

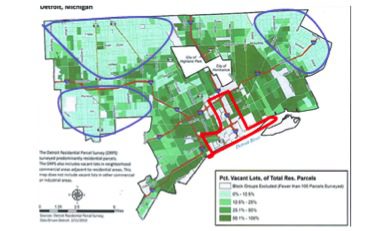

In the last few months, Neil Peirce's Citiwire.net has hosted several pieces highlighting positive things happening in Detroit along the lines of “the wave of young and mid-career professionals who're moving to Detroit.” Having spent much of the last nine months working in Detroit, I found this interesting but questionable. I don’t want to put the writers down, since I appreciate that they are trying to counter a lot of bad media headlines about the city, but what particularly struck me was that all of their good news was emanating out of a small part of Detroit, an upside-down T centering on downtown and Midtown (the area inside the red outline).

Now, areas like Midtown and downtown are not exactly thriving by most standards; both have more than their share of vacant lots and boarded up buildings. But they are starting to draw some market activity, and some — although hardly a wave — young and mid-career professionals. And the revival of Southwest Detroit, which has become a center of Mexican life and activity, is exciting. But it made me wonder.

I’ve spent quite a bit of time looking at middle-class Detroit, and what I think of as the city’s “middle-ground” neighborhoods. Not the devastated areas (dark green on the map) or the upside-down T, but the large areas (the major ones are shown in blue outline on the map) that have been the heart of Detroit’s (largely African-American) solid working class and middle-class for the last few decades. As the map shows, they dwarf the upside-down T in area, as well as in population.

If one accepts (as I do) the proposition that a healthy, mostly home-owning, middle class is a critical element in a city’s health, Detroit’s numbers for the past decade are positively scary.

While the city’s overall population dropped by 25 percent, the number of residents who have jobs dropped by 39 percent, the number of married couples with children dropped by 39 percent, and the number of households earning more than $50,000 dropped by 34 percent. Countering optimistic notions about a wave of young professionals, the number of people aged 25 to 34 also dropped by 39 percent. This contrasts with cities like Pittsburgh or Philadelphia, where the population in that age group grew strongly over the decade.

The human face of these numbers is visible across the middle-ground neighborhoods. Houses that sold for $100,000 five or six years ago are now selling for $20,000; vacant, boarded houses are popping up on hitherto well-kept streets (see picture); and more and more, houses are not being bought by homeowners, but by speculators. In the next Wayne County tax auction this fall, over 20,000 single family homes, nearly all in these neighborhoods, are likely to be auctioned off for back taxes. With most of Detroit’s nearby suburbs highly affordable to anyone with a steady white-collar or industrial job, Detroit’s middle-class is fleeing the city. This is a part of Detroit’s reality that isn’t making it into the media or the blogs, which seem either preoccupied with the city’s devastation, a genre that has come to be called “ruin porn,” or with proffering feelgood stories as a counterweight to the horror narrative.

My point is not to mourn the sad state of middle-class Detroit and its neighborhoods, but to raise some questions about cities and how we should be looking at their future. Even if the most optimistic reports about the Midtown and downtown trajectory are accurate (which I doubt), is that enough on which to rebuild a city? And, if the historically middle-class neighborhoods of the city should largely collapse, can a small downtown core surrounded by concentrated poverty and physical desolation, reminiscent perhaps of ancien régime Paris, be a socially and economically sustainable place?

I don't know the answers to these questions, but I suspect that they are more “no” than “yes” answers. A strong downtown and Midtown are important, but I suspect that Detroit's future as a healthy city is going to hinge upon its ability to stabilize some, if not all, of its middle-ground neighborhoods. How to do this, and whether any such effort comes too late for many neighborhoods, is another issue that remains to be addressed.

Comments