In the end, Mickey Mouse won. But it wasn’t the clean slam-dunk he’s been accustomed to in Anaheim, since Walt Disney bought 160 acres in sunny southern California and opened Disneyland in 1955.

It took much of 2007 and at least a couple of million dollars for The Walt Disney Company to prevail in a high-profile fight against a development that could have brought as many as 225 affordable rental units to an area near Disneyland. The Mouse pretty much scuttled the development, but the battle energized a nascent grass-roots movement unlike any other that Anaheim, population 328,014 and Orange County’s second-largest city, has ever seen.

The coalition in the Disney fight, Orange County Communities for Responsible Development (OCCORD) has turned its attention to bringing affordable housing — along with decent job standards — to city-owned land in the heart of a new mega-development, an 840-acre spot called the Platinum Triangle. But the residential project that drew Disney’s ire last year and sparked an epic community fight was one launched by SunCal Companies, a developer based a few miles from Anaheim in Irvine, Calif.

SunCal planned a 1,500-unit condominium project near Disneyland, most of them for sale, but with 15 percent set aside for rent at affordable rates. That project ran aground in November 2007, but only after expansive months of legal wrangling and City Hall skirmishing on Disney’s part and, ultimately, an assist from the tanking housing market. It’s likely Disney brass was caught off guard by the fight, both high-profile and protracted, required to win. The Mouse had, for decades, gently swayed Anaheim municipal policy through lunches, golf outings, and strategic political back scratching. Anaheim Mayor Curt Pringle, for example, not only opposed the SunCal project as an elected official: he became a face for a Disney-organized “grass-roots” coalition that opposed it.

A couple of years prior, The Mouse persuaded city officials to cough up a staggering $550 million for new roadways, along with creating a special tax district. This was to aid Disney’s then-on-the-drawing boards California Adventure park — one that has performed so dismally that Disney now plans a $1.5 billion overhaul.

The SunCal fight drew international headlines, but the real noise rumbled forth from a scrappy grass-roots coalition that brought a new, previously unheard voice to the policy debate — that of the tourism workers that drive Anaheim’s tourism and entertainment-based economy.

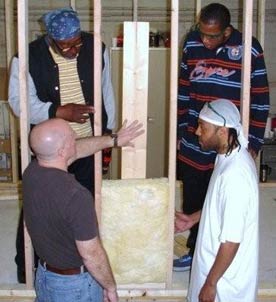

The rank-and-file from UNITE HERE, the hotel and tourist workers union local composed largely of Latino immigrants, showed up at City Hall, packed council hearings, and held demonstrations to back the SunCal affordable-housing proposal. Those employees hold the jobs that average an $11 hourly wage. Affordable-housing advocates estimate it takes $28-per-hour-plus to pay rent on a two-bedroom apartment in Anaheim — typically $1,400- to-$2,500 a month.

The workers’ presence at City Hall forced what might previously have been a corporate backroom battle out into the open, and, activists say, helped the City Council hang tough for as long as it did. “They’ve never had this particular demographic come to City Hall,” says City Councilwoman Lorri Galloway, the council’s strongest affordable-housing proponent. “Without the resort area workers, where is the success of this economic engine everyone talks about?”

Three strategic community partners joined together in ad-hoc coalition in support of the project — UNITE HERE, the Kennedy Commission, a coalition of community organizations supporting housing opportunities for working families, and OCCORD, a labor-community coalition formed in 2005 with support from UNITE HERE.

The coalition partners saw the SunCal project as a positive precedent in housing creation for Anaheim’s tourism workers. Disney is by far the largest employer in the city, which lies about 40 freeway miles south of Los Angeles.

The SunCal conflict flared into public view after an April 26, 2007 Anaheim City Council vote in favor of a change to Anaheim’s General Plan for an area known as the Resort District. The 2.2-square-mile area includes two Disney theme parks and a host of hotels and was zoned in 1994 to exclude any development that did not support tourism.

The April 2007 council vote approved a zoning overlay that permitted residential development in the district if 15 percent of the units were affordable — a seemingly modest approach given that Anaheim’s affordable-housing strategic plan calls for a mere 1,328 new affordable units between 2006 and 2001.

California law does not require cities to build affordable housing, only plan for it, setting goals in the housing elements of a municipal general plan, says Cesar Covarrubias, senior project manager for the Kennedy Commission. “If it doesn’t happen by the end of the planning period, the state doesn’t do anything,” Covarrubias says.

David Rusk, a former mayor of Albuquerque and former member of the New Mexico Legislature who is currently a Washington, D.C.-based urban policy consultant, says New Jersey is the only state that does have a clear statewide mandate, although the law allows what he calls loopholes. While Illinois, Massachusetts, and Connecticut have statewide policies, “I would not consider any very vigorous,” Rusk says.

Comments