The National Fair Housing Alliance (NFHA) is having its National Policy Conference in Washington, D.C., from June 8 to 11. This conference will shed light on salient issues on housing and lending discrimination, fair housing enforcement, and new strategies towards racial integration. Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.) will deliver a keynote address on Monday morning (June 9).

The National Fair Housing Alliance (NFHA) is having its National Policy Conference in Washington, D.C., from June 8 to 11. This conference will shed light on salient issues on housing and lending discrimination, fair housing enforcement, and new strategies towards racial integration. Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.) will deliver a keynote address on Monday morning (June 9).

On June 10, I am scheduled to speak at a panel discussion titled “The Costs of Discrimination and Segregation.” My presentation is titled “Segregation, Predatory Subprime Lending, and Community Impacts.” Joining me will be panelists who are authors of chapters in a recent book I and James Carr edited, Segregation: The Rising Costs for America. The other panelists include Margery Turner of the Urban Institute, who will speak about the impact of residential segregation on employment; Deborah McKoy of the University of California, Berkeley, Center for Cities & School, who will speak about the impact of segregation on education; and Gregory Squires of George Washington University, who will speak about broader public policies for the well-being of Americans.

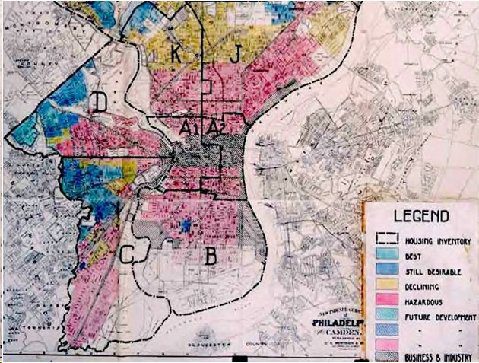

A fundamental point I shall make is that redlining of the 1930s and subsequent decades would not have been possible without residential segregation. And the reverse redlining, seen powerfully in the 1990s and 2000s, could not have been possible without residential segregation. It is segregation that made these discriminatory practices efficient from the point of view of lenders and other real estate professionals. They could focus their marketing, sales efforts, branch offices, etc. within well-contained geographic areas, instead of having to disperse their resources. The same types of neighborhoods that had been denied mainstream mortgage credit through redlining were specially targeted in the 1990s for readily available abusive loans through reverse redlining.

Much of the subprime predatory lending—the dodgy products that have sparked a global financial crisis—was piloted in minority neighborhoods, and on African American and Latino households. The subprime lending industry learned valuable lessons during this period of free reign on minority neighborhoods; lessons that they applied to other parts of the market. So that in the 2000s, white households, and even prime borrowers, found themselves exposed to dodgy products that they had been enticed into by well-practiced lending professionals.

When Martin Luther King Jr. spoke about being “caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny” and that “whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly,” he was probably not talking about the subprime mortgage crisis of the early-21st century. But these words aptly describe the current situation.

This is an elegant and thoughtful analysis that penetrates to the heart of the damage segregation does to our society. In Western Canada, similar practices prevail, but they tend to be directed at aboriginal people rather than African Canadians. And, as I’m sure Dr. Kutty knows, the segregation that lays the basis for red-lining and reverse red-lining is often about class rather than race.

Segregation goes even farther than that. It’s become something of a fetish in North America. As we all know, there are places where only old people can live, places deliberately developed to be suitable only for young adults, places designed only for families, with no room for old or unmarried people – that’s in addition to the standard practice of ensuring that every neighbourhood is suitable only for people of very similar economic circumstances. All this is supported, not only by our personal biases and by marketing categories, but also by zoning and building code regulations.

I don’t think we pay nearly enough attention to the political and social implications of fragmenting our society into tiny, narrow interest groups. I guess no one has figured out a way to turn it into a sound bite.

Thanks for a thought-provoking piece. Chris Leo.

Christopher Leo, Ph.D,

Professor, Department of Politics,

University of Winnipeg,

Winnipeg R3B 2E9.

Adjunct Professor,

Department of City Planning,

University of Manitoba.

Research-based blog: https://blog.uwinnipeg.ca/ChristopherLeo/