|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

A growing number of community land trusts (CLTs) and shared equity programs throughout the country are responding to the escalating affordability crisis by providing and stewarding opportunities for housing with lasting affordability. At least 314 organizations have developed an estimated over 15,000 homeownership units with lasting affordability, and nearly half of shared equity homeowners are people of color.

Stefka Fanchi, CEO of Elevation Community Land Trust (Elevation CLT) in Denver, considers U.S. homeownership a paradox: “It’s such an opportunity for families to build wealth. It is also basically the foundation for the wealth gap.” The shared equity model mitigates this contradiction. Shared equity housing makes stable homeownership and its generational benefits more accessible to Black and brown families that might otherwise be excluded from them.

Organizations like Elevation CLT use the model to bring more homeownership opportunities to their communities and ultimately try to narrow that wealth gap. Elevation CLT is a rapidly growing community land trust that has realized success by diversifying its housing program and by building a strong network of public-private partnerships, fostering what Fanchi describes as an “infrastructure of equitable opportunity” for housing in Colorado.

Elevation CLT is one of many ambitious organizations contributing to the growth of the field. Our organization, Grounded Solutions Network, released a 2022 Census of Community Land Trusts and Shared Equity Entities, published by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. The report documents the prevalence, practices, and impact of the CLT and shared equity field. We found that the number of CLTs and nonprofits with shared equity programs grew by 30 percent between 2011 and 2022, and the number of housing units provided by these organizations grew by 120 percent. We also found a wide variety of approaches to organizational structure, program characteristics, and unit development. These trends show a potential for scale that can help solve the nation’s housing disparities and help bridge the racial homeownership and wealth gaps. These findings are presented in our online mapping tool.

Program Diversity

Shared equity homeownership is a model whereby an entity uses a one-time subsidy to provide a home at an affordable price, then imposes restrictions to limit the price of the home each time it’s resold to a new low-to-moderate income buyer. While the shared equity model comes in many forms, our census is limited to CLTs (excluding conservation land trusts) and nonprofits with shared equity homeownership programs (excluding nonprofits strictly providing cooperative housing). We also identified three local governments that administer or sponsor CLTs.

Despite limitations to the study scope, we found significant program diversity throughout the field. About 30 percent of CLTs fit the “classic model,” a nonprofit entity with a corporate community membership structure, a tripartite board, and land in trust. Other similarly aligned nonprofits and local governments have adopted shared equity to increase the supply of affordable homes and make more efficient use of subsidy dollars by preserving affordability.

About 20 percent of reporting organizations had existed for at least 10 years before they started their shared equity programs. We found that startup CLTs take an average of 3.2 years to establish a program, acquire a property, and sell the first home. It only takes half that time for existing affordable housing organizations, such as Habitat for Humanity affiliates, to add a CLT or shared equity program and sell a home. Existing organizations generally have higher staff capacity, more funding, and more established relationships than new CLTs to help grow their shared equity programs.

While Elevation CLT is a new organization using the classic CLT model, it has employed successful strategies to speed its growth. Elevation CLT got its start in 2017 as a foundation-driven initiative originally incubated by a non-traditional CLT, the Urban Land Conservancy. The organization became an independent nonprofit in 2021 and has grown by building relationships with key philanthropic and municipal partners.

Elevation CLT started with the intention of addressing the housing need in Denver and appealed to various funders, some of whom were, as Fanchi puts it, “not the usual suspects.” By emphasizing the inherent link between affordable housing and health, Elevation CLT acquired $7 million from the Colorado Health Foundation, Fanchi says, which contributed to a total of nearly $25 million from multiple funders.

Elevation CLT then went to municipalities for matching dollars to begin completing projects. After establishing connections and agreements with over 13 municipalities, its capacity shifted. Fanchi recalled how, initially, her team had to approach municipalities asking for additional funding to match what they had raised in order to get their plans off the ground. Now, the municipalities are the ones “knocking on our door…we have to be like, we can’t do it,” she says.

Elevation CLT has a new “problem” to solve. Having successfully secured resources to bring to municipalities, it’s now encountering a higher demand from municipalities than it currently has capacity to meet. It has piqued local government interest and built an enabling ecosystem for the shared equity model in Colorado, highlighting a need for greater response from the field to the demand for housing with lasting affordability.

Portfolio diversity

We also found diversity among CLTs’ housing portfolios. More than half of the organizations surveyed reported at least one other tenure type in addition to standard shared-equity homeownership, such as lease-to-purchase, cooperative housing, manufactured homes or resident-owned communities, and rental, the most common type. Many CLTs and shared equity entities recognize that their communities require an array of affordable housing options to meet the needs of people with varying circumstances.

A diverse selection of housing options can open possibilities for CLTs and shared equity programs to serve a wider variety of community members. As a result, individuals, families, or seniors can find an affordable home that suits them, including those who don’t want to or aren’t ready to purchase a single-family home. Multifamily rental housing may also be a good option for high-cost, dense metropolitan centers since more homes can be produced or preserved per parcel of land. Importantly, even with diverse portfolios, shared equity programs can still maintain a mission-driven, stabilizing, and community-controlled focus, particularly their commitment to lasting affordability. Nearly all nonprofits with shared equity programs restrict some or all of their rental units to residents with incomes no higher than 80 percent of the area median income (AMI), and 77 percent of programs require their rental units to remain affordable for 30 years or more.

CLTs can ensure equal representation for residents of all housing types through some of the same participatory mechanisms associated with traditional homeownership CLT models, such as board membership. CLTs can also partner with tenant organizing groups to intervene in the sale of multifamily developments, pulling them from the speculative market and ensuring stability and lasting affordability. In 2022, Elevation CLT partnered with residents of the Westside Mobile Home Park in Durango, Colorado, to raise capital and buy the land for the CLT to hold in trust, with plans to redevelop the park into new, permanent homes for existing residents. With the relationships they built through that effort in Durango, their team started a scattered site acquisition program, and was selected to develop a new 30-unit townhome project, bringing the total new units for the area to more than 100, Fanchi says.

“When we go into local small communities, [we’re] not going to have an office there,” Fanchi says. “We’re going to partner with existing organizations so that they can do those things that we would have done on the ground.” When her team completes a project, they don’t just leave behind a new set of homes. They also leave local organizations with more experience, new relationships, and a higher capacity to continue serving their communities.

Elevation CLT exemplifies how pursuing portfolio diversity can build valuable partnerships, especially with less established community organizations that have limited capacity and resources. Fanchi believes that organizations can challenge the common belief that resources are scarce. By pursuing creative collaborations, organizations can “approach [problems] from abundance instead of scarcity,” and “bring that abundance to other organizations.”

diversity in service area and property acquisition

CLTs and shared equity programs are often thought of as only neighborhood-based programs, a prevalent misconception that is not fully representative of the field. We found that 55 percent of CLTs and nonprofits with shared equity programs serve an entire city or county, 21 percent serve multiple counties or an entire metropolitan statistical area (MSA), and 7 percent of organizations in the study serve an entire state. Only 17 percent serve just one or more neighborhoods. To serve just one neighborhood may mean that an organization is limited in its ability to acquire enough land and resources to sustain its program and make a significant impact. Broader service areas can unlock more opportunities and choices for people facing displacement or lacking sufficient housing options in their neighborhoods.

Elevation CLT found that operating statewide has allowed the organization to be flexible enough to take on new projects in one area while addressing challenges that may arise from existing projects in another area. Additionally, Elevation CLT was able to secure a contract with the state of Colorado that allows them an additional subsidy–up to $40,000 per unit or $50,000 with a waiver, Fanchi says. The funds can be used to acquire, construct, or rehab homes in any partnering municipality that provides matching dollars for projects, but where the project might still be missing the full funding needed to bring it to life.

In the same vein, shared equity programs are implementing a variety of strategies for acquiring properties, allowing them to realize more growth, meet the housing demand, and take advantage of fluctuating market and funding opportunities. Beyond new construction and acquisition/rehab, other methods include partnering with for-profit or nonprofit developers; acquiring or managing homes for state or municipal entities, such as units created by inclusionary zoning programs; receiving discounted or donated land from land banks or other public entities; receiving private property donations; assisting current homeowners in distress to convert their property to shared equity; and implementing buyer-initiated programs, where potential homebuyers can identify eligible properties in the open market to bring into a shared equity program.

In 2023, Elevation CLT introduced a buyer-initiated program. It was originally designed as a special-purpose credit program with the intention of increasing the homeownership rates of BIPOC households in Colorado. The program provides homebuyers access to downpayment assistance loans of up to $50,000 in addition to Elevation CLT’s regular $50,000 permanent subsidy and a local matching subsidy or a state subsidy, Fanchi says. The process begins by connecting a prospective buyer with one of Elevation’s certified real estate agents and working to qualify the buyer for a mortgage while determining a maximum purchase price that works for them. With the help of the real estate agent, the buyer can then identify a home on the regular market that meets the requirements set by Elevation CLT’s program, which is called “Doors to Opportunity.” The program creates a mutually beneficial arrangement where the buyer is given the opportunity to find a home in a neighborhood of their choosing while adding a new affordable home to Elevation’s portfolio. The idea here is that buyers are not restricted to living in an area subject to gentrification, or where residents face displacement, but rather can decide on the area they want to reside in. Elevation CLT is among the 15 percent of programs in the study that acquired buyer-identified properties between 2017 and 2022.

racial equity and populations served

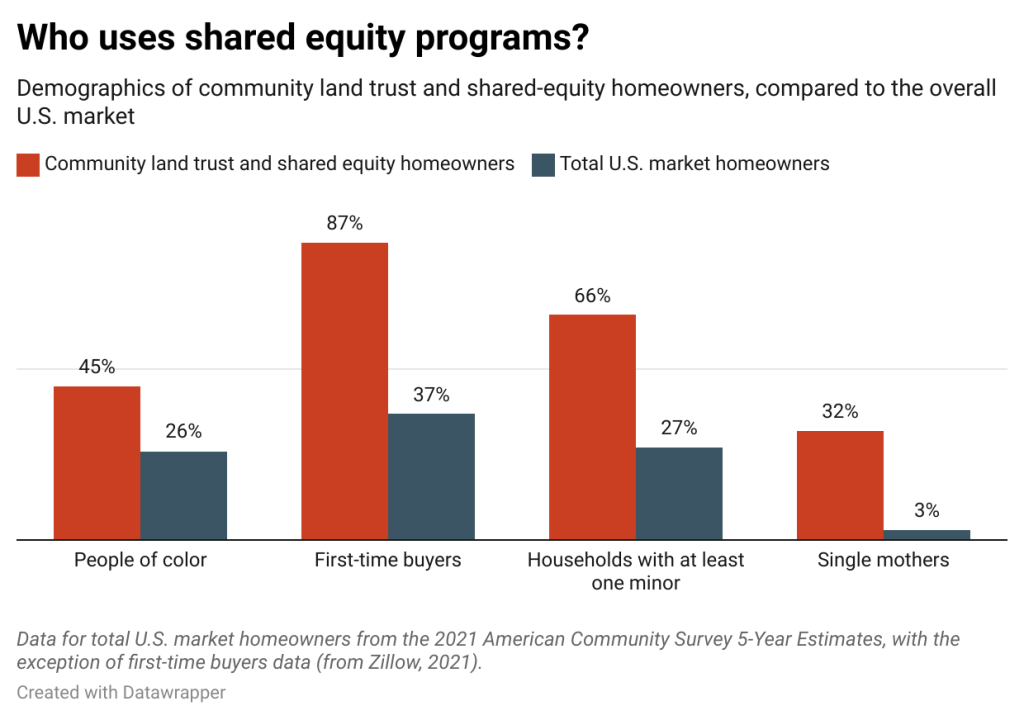

As it concentrates on growth, it’s crucial for the shared equity field to also focus on serving populations that are chronically excluded from homeownership opportunities. Our study found that the field is on the right track: 45 percent of all shared equity homeowners are people of color, whereas, in the broader homeownership market, people of color account for only 26 percent of all homeowners. Shared equity programs also outperform the broader market in other key demographic areas: about 87 percent of shared equity homes are occupied by first-time homebuyers, 66 percent have at least one dependent under the age of 18, and 32 percent of shared equity households are headed by a single mother.

While the study findings on racial demographics look impressive compared to the broader nationwide housing market, this context sets an inadequate benchmark due to significant underrepresentation of households of color in the market, resulting in a homeownership rate roughly 25 percentage points lower than white households. Shared equity programs offer a homebuying solution that helps eliminate some of the barriers to homeownership often encountered by people of color, and 58 percent of shared equity programs prioritize racial equity for BIPOC communities over economic equity and race blindness. How different programs prioritize equity may look different, however. Elevation CLT’s staff feel as though prioritizing equity doesn’t need to be an explicitly stated goal of the organization, but rather that focusing on racial equity should be inherent in the work of a CLT. They acknowledge the importance of “trying to advance homeownership…[in] a way that is not just equitable, but that is somewhat reparative of its past.” Sixty-two percent of Elevation CLT’s homeowners are BIPOC, Fanchi says.

Still, when Elevation CLT’s team was developing their “Doors to Opportunity” program, they were challenged by the state’s anti-discrimination act and found that the program could not be approved in its original form since it did not apply to white buyers. Consequently, Elevation had to pivot and focus on a “targeted marketing effort to try to get this program into the hands of BIPOC buyers without making race a qualifying factor for approval,” Fanchi explains. Elevation’s conflict with the Colorado Attorney General demonstrates that, even when explicitly working to dismantle structures of discrimination in the housing field, there will be setbacks and barriers that require creative solutions to ensure equitable homeownership and wealth-building opportunities for Black and brown communities.

average size of shared-equity portfolio

While a 120 percent increase in unit growth over the last decade is truly impressive, the field must grow even more. By applying unit growth rates of surveyed organizations to nonrespondents, we estimated that the field had produced a total of 43,931 residential units by the end of 2022, of which about 15,606 are shared equity homeownership units. On average, each nonprofit entity stewards about 97 shared equity homeownership units, while over half had no more than 50. In the face of an ever-growing housing affordability crisis, we must commit to immediate efforts to increase the affordable housing stock. Limited public and philanthropic funding for affordable housing can go much further when used to subsidize homes with lasting affordability. As of 2019, it was estimated that 6.6 million additional households could become homeowners if shared equity homes were available to them.

strengthening the field to meet demand

Our conversation with Elevation CLT shows that shared equity organizations can have an immense impact when the governments they work with help them realize their commitment to lasting affordability. Partnering with governments unlocks resources to develop more homes, helps CLTs to receive publicly acquired land, and enables CLTs to advocate for tax exemptions, subsidies, and equitable land use requirements. Shared equity programs can also broaden their approaches to portfolio growth, such as by expanding their services to areas with more opportunities for development and acquisition, partnering with tenant organizations and other nonprofits to buy and preserve affordable developments, working with single-family investors looking to offload their portfolio, approaching lenders to negotiate favorable arrangements for financing new projects, and pursuing other innovative solutions.

Amidst increasing demand for affordable units, Grounded Solutions Network is doing our part to grow the field of housing with lasting affordability. Our first capital fund, Homes for the Future, is one of six winning solutions presented for Enterprise and Wells Fargo’s 2023 Housing Affordability Breakthrough Challenge. The capital fund will support the direct acquisition of single-family rental homes from the speculative market, pay down each home’s principal with earned rental income, and then partner with local shared equity programs to place homes in their portfolios. This initiative will offer an alternative resource in places where public subsidies for acquisition and rehabilitation are less abundant and create homeownership and wealth-building opportunities for Black and brown communities.

The hard work and collaborative efforts by CLTs and shared equity programs throughout the United States have indeed resulted in more homes, more transformative practices, and more engagement from all corners of the housing sector. Our research uncovered innovative approaches to funding and acquisition, diversification of programs and portfolios, and an expansive ecosystem of public and private partnerships. Today, the field has an opportunity to harness this momentum and grow to an even bigger scale that can make affordable and secure housing a reality for more communities across the country.

Decades ago I did a poll that asked prospective buyers about shared-equity. While these households didn’t know how they were going to accrue a needed downpayment, they knew that they “wanted it all” and were generally not interested in shared-equity. As a niche activity, one will always get takers, but we need a discussion about how to make shared-equity that keeps housing affordable financially attractive to those who have more housing choices if the idea is to create a significant “social housing” sector.