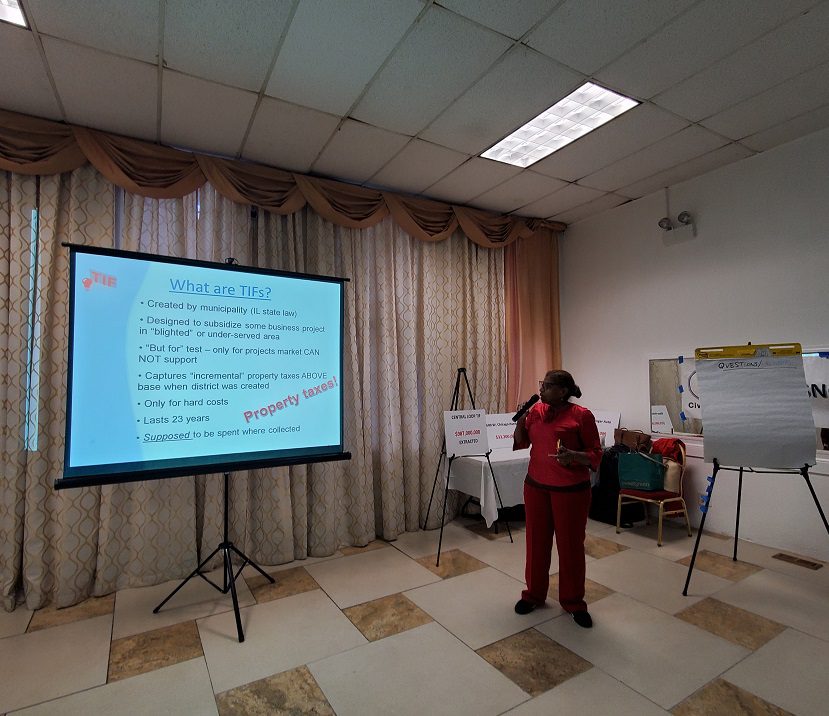

Eunice Mina, a volunteer organizer for El Pueblo Manda (The People Rule), translates a presentation explaining how TIFs work, how they raise property taxes, and the details of the major TIF district in the Pilsen neighborhood of Chicago, on April 27. Photo courtesy of Tom Tresser

When local governments want to kickstart development in areas that don’t draw large-scale, neighborhood-revitalizing projects, they don’t have many tools at their disposal. One popular yet controversial tool they can use to lure developers to build in disinvested areas is called tax increment financing, or TIF.

TIF is a financing mechanism that’s favored by governments and largely misunderstood by the public—even though they’re paying for it.

The basic TIF program structure goes like this: A city or county government designates a disinvested (often called “blighted”) area as a TIF district. This designation allows officials to split the property tax revenue the district generates. The current amount of tax revenue collected within the district’s boundaries is set as the “base rate.” This is the portion of taxes that currently pays for—and will continue to pay for—community services like schools, libraries, public safety, roads, etc.

Officials then project what the future tax revenue within the district will be once the revitalization project is complete. The difference between the base rate and the projected property tax revenue is the “increment” referred to in the program’s name. This portion of taxes is what’s sequestered from a local government’s general operating budget and used to subsidize developers who build in those disinvested areas.

Supporters say TIF is justified in redirecting a portion of taxpayer dollars to developers because without the redevelopment, the additional property taxes wouldn’t exist. The subsidies, they argue, make development financially feasible. Detractors argue TIF programs are little more than a public handout to the private sector—a flawed funding mechanism with racist underpinnings that diverts much-needed money from important civic services.

TIF in Theory vs. Practice

At least 10,000 TIF districts exist across the U.S. Allowing for minor variances, most of these TIF programs work similar to each other: Distressed or underutilized neighborhoods are turned into TIF districts to attract developers. Most states give cities (and sometimes counties) the discretion to create and administer TIF districts. New TIF districts are initially established for a set number of years—usually between 15 and 50. While the term limit seems like it would cap the amount of forgone revenue a TIF district can withhold from a city’s general operating budget, it doesn’t always work that way. In some places, a district’s TIF status can be renewed upon expiration (often at the local government’s discretion and without public input). In Illinois, for example, new TIF districts divert tax revenue for 23 years and can be renewed for an additional 12 years.

In theory, TIF should pencil out. Future anticipated tax revenue increases generated by the new developments should match the projections. But, of course, economies change. Future developments and neighborhood changes don’t always increase surrounding property values (and subsequent tax revenues) enough to support the projections.

But by that time, the projects exist and the developers have been paid. Local governments often issue bonds backed by the future projected tax revenue. Doing this generates capital up front, allowing developers to recoup their initial investment quicker. TIF can also be financed through a pay-as-you-go method: the government repays the developer incrementally as the tax revenue is received. This creates more risk for the developer and is therefore less popular.

It can happen that the TIF district or project doesn’t generate enough profit to pay the debt service, leaving local governments holding most of the risk when issuing TIF-backed bonds. Say the economy turns and property values decline. Maybe a development project is inherently flawed or the government miscalculated the increment amount. When a TIF is “underwater,” the local governing body typically won’t allow the bonds backed by it to default, meaning the district can become a drain on a city’s general operating budget. For example, during the mortgage crisis, Kansas City, Missouri, had six underwater TIF districts.

Most states put very few restrictions on TIF districting aside from requiring them to pass the “but-for” test: Before creating a TIF district, local governments must determine that the development they’re subsidizing would not have happened but for the use of TIF. This justification allows cities to set a base rate—assuming tax revenue would have stagnated at that rate “but for” the new development—and start redirecting any revenue over that amount for the TIF district. The problem is that the criteria for passing the but-for test are “so elastic.”

“Who’s the but-for judge?” says Tom Tresser of the CivicLab, a nonprofit based in Chicago that focuses on government accountability. “Well, it’s the consultants first and then the staffers at the planning department. They’re the ones who make the decision that the but-for condition has been satisfied. The whole thing is a joke.”

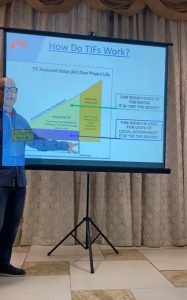

Tom Tresser explains TIFs at a community meeting. Photo courtesy of Tom Tresser

This flexibility and lack of public input or oversight makes TIF both popular (with developers) and ripe for critique. The CivicLab wants TIF ended in Illinois, for example. Folks in Albany, New York, and Bozeman, Montana, also want TIF programs abolished in their states. Rick Rybeck, founder and director of Washington, D.C.-based economic development consulting firm Just Economics, thinks of TIF as “kind of a smoke-and-mirrors thing.” TIF proponents argue that without a TIF-funded project, property taxes in the area would remain static year after year. If that’s what happens, developers would say TIF is working as it’s meant to: by generating revenue without depriving a city’s general operating budget.

“So the TIF is like this gift from heaven, a way of telling people we can pay for this new development without costing them anything,” Rybeck says. “But it’s very rare that this is evaluated on a rigorous basis. And I think if you look at history, you’ll find it’s very rare to find an area where tax revenues are flat.”

Tresser argues that even without investment, the areas designated as TIF districts would have seen their tax revenues increase at the same rate as the general tax district they were part of. Because TIF districts are carved out of larger, existing tax districts, claiming their tax revenues would be flat independent of the city or county around them is unlikely.

An Eye on the Windy City

In Chicago, activists have long claimed that the city’s TIF program is more a corporate handout and mayoral “slush fund” than it is a catalyst for economic or community development. They say TIF transfers billions away from typically underfunded public services and into corporate developers’ pockets.

For the last five years or so, a handful of local journalists, activists, and academics have publicly called out Chicago’s overactive TIF districting and spending habits. (The city comes by its largesse honestly; Illinois is one of six states with more than 1,000 active TIF districts.) Tresser and Jonathan Peck, cofounders of the CivicLab, are two of those activists. In 2013, the CivicLab launched the TIF Illumination Project to investigate Chicago’s 100-plus TIF districts and report their impacts on the city’s tax base. They determined that TIF districts have commandeered about $10.3 billion in property tax revenue from the city’s general operating budget since Chicago implemented the program in 1986. In 2021 alone, the city’s TIF districts sequestered $1.08 billion in property tax revenue—around half of that would otherwise fund public schools (which are facing a budget shortfall).

“Chicago and hundreds, if not thousands, of municipalities across the U.S. are removing billions of public property tax dollars from circulation . . . to subsidize projects of little to no public value,” Tresser wrote in an email. “The number one victim of all this subterfuge is America’s public schools.”

Two specific downtown projects funded with $1.6 billion in TIF subsidies, The 78 and Lincoln Yards, inspired protests and a lawsuit, with plaintiffs arguing that the sites didn’t qualify as “blighted.” But the TIF controversy isn’t new. Reports from 2015 show nearly half of the city’s TIF revenue was being spent inside The Loop—a popular and economically prosperous area. A 2017 study found nearly 35 percent of TIF-related spending in one Chicago district was “questionable.” A 2010 audit found “improper spending and oversight of TIFs.”

What gets opponents is the “proper spending” they believe is anything but. For example, when boom years generate more TIF revenue than projected, the mayor can declare a surplus. The 2022 Budget Overview designated a TIF surplus of $271.6 million. In 2020, it was more than $300 million. The mayor’s office is statutorily allowed to reallocate surplus TIF dollars to non-TIF related projects with no public input or oversight. It’s this opacity opponents find problematic, saying it allows the mayor to pad favorite developers’ pockets.

Another problem? Porting. State statute allows local governments to transfer money between TIF districts that share a border. While porting ostensibly facilitates “regional projects,” Tresser calls it “a skim inside of a skim.” CivicLab’s research determined that porting favors majority-white districts at the expense of majority-Black districts. For example, in 2021, majority-Black wards contributed nearly half of the money Chicago had in its TIF accounts, while majority-white wards contributed less than one-third, according to CivicLab research. But the city’s 18 majority-Black wards received less TIF money than the 14 majority-white wards.

The TIF Illumination Project participants believe tax increment financing as a public funding mechanism is too open to corruption in its current iterations, and its results are too racist for the program to be salvageable. The CivicLab is currently working with local activists from about 15 counties and cities across the nation to uncover what local TIF districts and associated projects look like in their areas. Eventually, the group would like TIF eliminated nationwide.

From the Windy City to the Motor City

The Detroit People’s Platform—a grassroots, Black-centered economic justice nonprofit organization—learned about the CivicLab’s TIF Illumination Project while investigating how Detroit commercial developers were fulfilling the terms of their community benefit agreements (a city ordinance requiring developers to proactively engage with a community to identify benefits and potential drawbacks of specific projects). Theo Pride, a community organizer with Detroit People’s Platform, says his team had heard of TIF but didn’t know what it was or how to track down how it’s administered in Detroit. The group hired the CivicLab to help create a “road map.”

|

The CivicLab can show you how to investigate your own local government. CivicLab is seeking activists who want help tracking TIF districts and expenditures in their city, county, or state. |

“We began to excavate,” Pride says. “We began to look at entities; a lot of them we were already familiar with. It was just about getting into those more clandestine spaces where TIFs dwell to pull out the information we needed.”

Pride says the CivicLab’s coaching helped Detroit People’s Platform figure out how TIF works, including that the program is set up differently in Detroit. Because TIF in Detroit is distributed differently than in Chicago, the CivicLab and Detroit People’s Platform had to adapt the TIF Illumination Project’s research techniques and investigative procedures to find the information the organization was looking for. They learned that rather than creating designated districts in which taxes are segregated and held for specific projects, Detroit developers apply for TIF reimbursement on a property-by-property or project-by-project basis.

Two city offices are responsible for managing and distributing nearly all the money being captured by tax increment financing in Detroit: the Downtown Development Authority (DDA) and the Detroit Brownfield Redevelopment Authority (DBRA, pronounced like Deborah). Both the DDA and DBRA are administered by the Detroit Economic Growth Corporation (DEGC). The DDA provides loans, sponsorships, and grants to private businesses and investors, while DBRA manages redevelopment of sites the city has designated as brownfields.

Some of Detroit’s TIF money is earmarked for downtown (and therefore is administered by the DDA). The remainder is used by DBRA to reimburse developers for qualifying projects in several areas, called Opportunity Zones and Council Districts. On its face, reimbursing developers for cleaning up and improving brownfields seems like a good plan—Detroit’s industrial and manufacturing industries left dozens of contaminated parcels in and around the city center. But in practice, the city’s definition of brownfield is so broad and vague that, says Pride, “developers essentially can come in and get a brownfield [TIF reimbursement] for anything.”

(According to the Environmental Protection Agency, a brownfield is a property “which may be complicated by the presence or potential presence of a hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant.” Emphasis added.)

“It’s not being used to reactivate old industrial land into a useful development,” Pride says. “It’s just being used so developers can make more money and the development will be more profitable.”

The result is that the city is funneling taxpayer money away from schools and neighborhood services to subsidize multimillion-dollar projects usually proposed by white developers, says Pride. In Detroit, that developer is often Dan Gilbert, the billionaire co-founder of Rocket Mortgage, who owns and is redeveloping substantial real estate in downtown Detroit. Gilbert’s real estate firm, Bedrock, in 2018 secured $618 million from DBRA to offset costs on the Hudson’s project, a 12-story office and event space and a 49-story high-rise with a hotel and luxury residences. The 1.5 million-square-foot project—which is still under construction and is expected to cost $1.45 billion by the time it’s complete—recently received an additional $60 million in tax credits from the city. Opponents call the most recent tax abatement a “handout to one of the world’s richest men.”

Detroit People’s Platform was one of many vocal opponents to the Hudson’s development, and though they couldn’t stop the city from approving the most recent tax abatement, Pride says the “community came out in droves” to oppose giving Gilbert the additional $60 million infusion. Their oppositional presence at city council meetings delayed the vote several times and forced Gilbert to negotiate additional affordable housing and other community benefits, Pride says.

“It got approved eventually, but not without a fight, and we see that as an example of the discourse changing and the politics changing around this.” Pride says the DEGC rarely does any type of community outreach but thanks to a groundswell of opposition “decided to go on a city tour to educate people about TIFs and tax incentive development.”

[RELATED ARTICLE: Who Can Afford Housing in Madison, Wisconsin?]

The DEGC held a series of community events pushing the benefits of TIF, explaining why and how it stimulates development in Detroit, Pride says. But Detroit People’s Platform organizers had already presented what they learned from their work with the CivicLab to the Detroit public via several community meetings. Pride says that outreach “created some momentum” for the pushback campaign against Gilbert’s $60 million ask.

“We showed up with all our TIF stuff we got from the CivicLab,” he says. “We showed them the data and the research, and we pushed back against their narratives.”

The meeting mentioned in the article was hosted by El Pueblo Manda (www.tinyurl.com/EPM-Facebook). It was the CivicLab’s 187th public meeting. They are organizing to stop the relentless gentification threatening their community. You can learn more about this at https://tifreports.com/pilsen-organizing. Our awesome collaborators at Detroit People’s Platform has published a number of community engagement materials to explain TIFs – see https://www.detroitpeoplesplatform.org/tax-incentive-ed. Reach us at [email protected].

Typically TIF is used as a bipartisan tool to facilitate the upward redistribution of wealth….

Andy – You got that right. Where are you located? Have you engaged in some work or campaign around TIFs, economic justice, community organizing, etc? You can email me directly if you like, at [email protected].