Photo by Flickr user Alan Wolf, CC BY-NC 2.0

Doug Holtz starts his workday at 8 a.m. He manages underwriting for Madison, Wisconsin’s community radio station, WORT. On the first Monday in April, Holtz had been at his desk in the basement of the station for about an hour when an email came in from his landlady, telling him that she wasn’t going to renew his lease. This is the third time in 10 years that Holtz has been forced to move, and over that decade, his rent has doubled.

Doug Holtz

“I’ve paid my rent early every month. I’ve never had a rental payment be late . . . in any of these three apartments. Never had a noise complaint. Nothing.” Still, Holtz says, his exemplary conduct hasn’t translated into stable or affordable housing.

“I’ve been a model tenant, yet I still get treated like dirt, totally like dirt, which is because these people have enough money to treat me like dirt, and so they do,” he says.

Holtz, who is 56, earns $45,000 a year and is paying $1,380 a month in rent at his current home. That’s nearly $300 more than what the city points to as “affordable” for people earning salaries like his. The news that he will have to find a new place to live within the next three months—and that the new home will likely be much more expensive to rent—has prompted panic attacks and sleepless nights.

“I make too much money for affordable housing, and I make too little for unaffordable housing. I’m in that gap in between,” Holtz laments. “What am I supposed to do? Eat oatmeal for the rest of my life?”

Holtz isn’t alone in his frustration. Nearly half of all renters in Madison qualify as rent burdened or severely rent burdened. Holtz fits the former category, which means he is paying more than 30 percent of his income on rent. In a severely rent burdened household, rent eats up more than half the income. This situation has worsened over the last several years in Madison, which earlier this year saw the highest year-over-year percentage rent increases among the top 100 U.S. cities, according to Apartmentlist.com. Madison renters are also experiencing surging competition for limited housing from an influx of newer, wealthier residents. As with Austin and San Francisco, Madison’s affordability issues tie into its growing tech sectors.

Those factors, along with the relatively low wages of non-tech jobs within the city, are pushing natives like Holtz out of Madison.

Housing for Whom?

Housing is being built in Madison, though. A lot of it, and at a pretty rapid clip.

The city has issued more than 18,000 new housing permits since 2013, most for market-rate units. A large percentage of those units have been built in the city’s downtown area, which sits between two bodies of water, forcing development upward. Multiple high-rise buildings have gone up there over the last decade, and today, cranes dot the skyline and some streets have taken on a canyon-like feel.

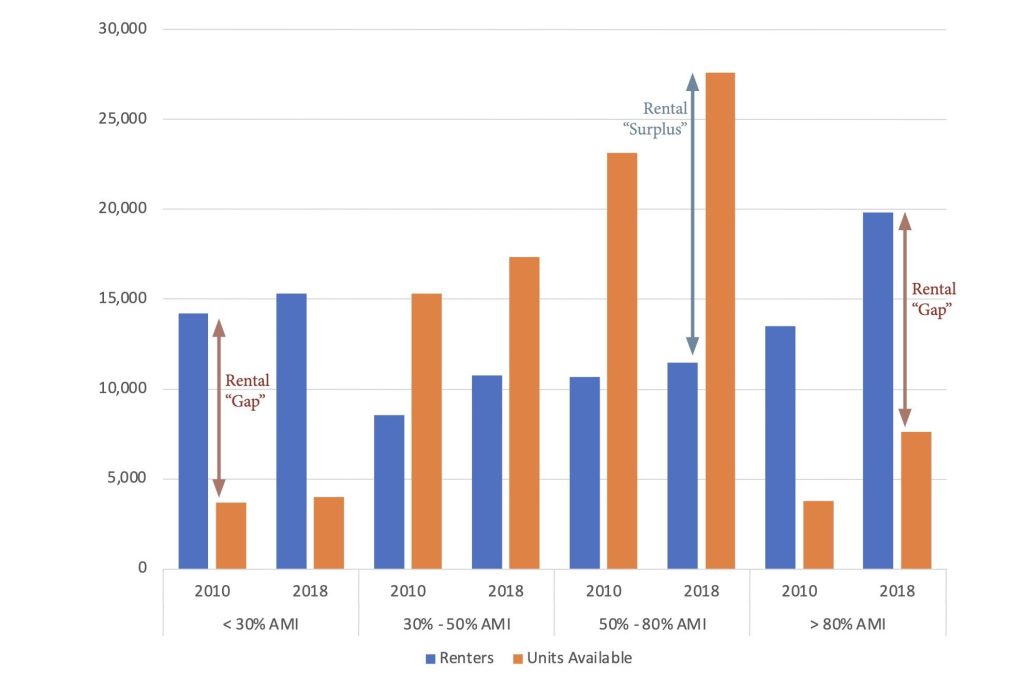

Even so, Madison’s supply of rental units still lags compared to demand. The city is attracting thousands of new residents each year, with the population projected to grow by a staggering 42 percent in the next 30 years. The demand for market-rate housing from households earning more than the city’s $70,000 area median income, and the limited affordable housing options for those earning less, make it difficult for folks like Holtz to compete for an apartment. There’s a shortage of new, more luxury housing for renters earning higher incomes—say around the $100,000-plus range—and “these households ‘underconsume’ (rent-down) within the housing market, which means units they rent are incredibly affordable to them,” according to Madison’s 2022 Housing Snapshot Report. In effect, they’re taking these more affordable market-rate units away from lower-earning renters.

Via Madison, Wisconsin’s 2022 Housing Snapshot Report.

Affordable housing is being built, but at a much slower clip. From 2013 to 2022, the city has supported via its Affordable Housing Fund almost 2,000 affordable housing units, about 1,500 of which have been built or are currently under construction. Most of the affordable housing efforts have prioritized households that earn 50 to 80 percent of area median income—creating what the city calls a surplus of housing for that income level. Take for example a 550-unit affordable housing project that was recently approved on the site of a decommissioned Oscar Mayer processing facility on the city’s East Side. The development aims to serve households earning $40,000 to $90,000 per year.

But someone working full-time as a laborer with the city’s convention center would earn just under $34,000 annually, too little to meet the lower threshold for that development. While this position sits near the bottom end of the city’s wages, it illustrates the challenge low-income residents face.

But perhaps the biggest challenge is addressing the housing needs of extremely low-income residents, those who earn 30 percent of the area median income, or $24,250 for an individual. According to the city, there’s a shortfall of more than 11,000 units for folks in this income bracket. Data from Madison’s Affordable Housing Fund shows that only 13 percent of the affordable units recommended for approval in 2022 targeted this demographic.

Justice Castañeda is a Madison native and former Marine who now runs Common Wealth Development, a community development organization that offers low-income housing. “We need to focus and aggressively pursue housing for people who earn under $40,000, and we need to do that in spades, and that should be the top priority, and that should be the way that we talk about it and we should say that,” says Castañeda, who critiqued the city’s approach of pushing new housing development for all income levels, including those able to afford market-rate units.

As it stands, the city does provide financing to private developers who build affordable housing through its Affordable Housing Fund. And according to Linette Rhodes, who supervises community development grants for Madison, “we are trying to use other mechanisms, like [tax-increment financing], to support the growth of affordable units.”

But things like inclusionary zoning, which would require developers to build below-market rate housing units in new construction projects, and rent control, which could curb the high rent increases Madisonians are facing, are not options the city can take. Wisconsin bans municipalities from setting rent regulations, and it prohibits inclusionary zoning. This complicates matters for local policymakers who are trying to solve Madison’s housing conundrum. Nonetheless, Castañeda says, “Cities say they don’t have control, but they don’t leverage the power they have.” He acknowledged that it’s not as simple as pressing a button to solve the problem saying that the city’s challenge is developing a sustained course of action. Still, he wondered whether Madison is not leveraging all its options because of fears that questioning development would appear contrary to the idea that the city needs all the housing it can get regardless of what the rent is.

Faced with restrictions on zoning, municipalities like Madison often turn to Low-Income Housing Tax Credits to help bolster affordability. In exchange for developing affordable rental housing, these tax credits enable investors to lower their tax liability over the credits’ roughly 10-year life span.

Some experts, however, say the tool is being overused. “LIHTC, because it’s the only game in town, everybody tries to fit every policy objective onto it,” says Dr. Kurt Paulsen, an urban planning professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who studies affordable housing financing.

“One of the policy arguments in favor of [low-income housing tax credits],” Paulsen explains, “is that you’re offloading property management and tenant selection to a private-sector entity.” But he notes that a private business “may not have the same social intention as a city” and so might select tenants with somewhat higher incomes or less blemished credit records, disregarding people with more challenging histories. Those people, however, are often a city’s most vulnerable population.

[RELATED ARTICLE: Challenging the Almighty Credit Score]

One reason tax credits fall short when it comes to ensuring housing for lower-income residents is that the state allocates federal tax credits and has to distribute them to cities across the state, creating competition for a limited resource. Those credits come together with other sources of funding, including the city’s own affordable housing development fund, to piece together project financing.

Another reason is that low-income housing just doesn’t make as much money for the developers.

“Permanent supportive housing sub 30 percent AMI for people at risk of homelessness—very hard to do with [low-income housing tax credits],” Paulsen acknowledges. He estimates that over the 10-year lifetime of a tax credit on a 50-unit building, the cost difference between a two-bedroom unit renting at 60 percent of AMI and one at 30 percent of AMI amounts to roughly $3 million.

“So, I always tell people, for the same two-bedroom unit, the difference between a 60 percent AMI unit and a 30 percent AMI unit is that you have to put up much more tax credits upfront,” Paulsen says.

Searching in Vain for an Apartment

For Holtz, losing his lease means having to search for a new home in an extremely tight market. The rental vacancy rate currently sits at 2.5 percent, half what is considered healthy.

“I went on a couple of apartment-hunting sites, and there’s nothing. There’s really nothing,” Holtz says. “Where I’m living now, to find something comparable would be over $2,000 a month, and I don’t have over $2,000 a month.”

Holtz is not low-income, yet his dilemma highlights the housing challenges facing a broad swath of Madisonians. As a result, some housing advocates are pushing the city to consider new approaches. Dr. Olivia Williams, who runs the Madison Area Community Land Trust, is one of them. One strategy she endorses would have the city get more creative with the way it finances affordable housing projects.

“What we could do is use our bonding authority to basically borrow and produce social housing that might be mixed income and cross-subsidized units between high-income units and low-income units,” Williams says. “That model theoretically can pencil out and work, especially because . . . a city can borrow at much lower rates than a bank would require, especially right now.”

The city is looking at opportunities such as land banking, says Rhodes, which would set aside city-owned land for future housing development.

New Markets Tax Credits represent another potential tool for the city. Another possible lever comes from a controversial Obama-era program, Rental Assistance Demonstration, or RAD, which gives public housing authorities the ability to make use of private financing to preserve and repair aging buildings and units. The program is a workaround for the 30-year gap in federal funding for public housing.

[RELATED ARTICLE: Does RAD Privatize Public Housing?]

Holtz’s future remains uncertain, but he may have a way out. Last year a driver ran a red light and blindsided Holtz’s car. The accident left him with broken ribs and a totaled car, but he hopes that the settlement will come through before his lease expires at the end of June. If it does, Holtz says he will try to qualify for a minimum downpayment as a first-time homebuyer.

“I’m hoping for the universe to provide that out because other than that, I don’t see a lot of options, other than pitching a tent in my kid’s backyard.”

great article on the challenges renters are facing in many communities and possible solutions – one factor causing prices to go up is 10+ years of low interest rates which created high demand, so the federal government has played a role in this crisis

To the author, Zo Sullivan, and the respected bright contributors to this, Thank you.

To the research staff, data analysts, and editors, who had to have put in some painstaking hours to be able to compile this down to such an excellent read, simply laid out. Thank you.

As far as this long-term resident who works hard for a living and has been an excellent tenant who has always paid his rent.. the answer to me a simple..” Due to the enormous increase in rental properties in the city of Madison over past ~~~

Years. We are going to put a temporary one year emergency moratorium on all current tenant lease’s effective June 1. In other words, these residents that are like this similar to his story, and there are many of them hundreds of them, if not thousands. So another words, the person in your story here will be able to remain in his apartment on the current lease he has with no increase for one year until there is an evaluation. I mean you could say we were raising your rent 2% or something but I guarantee you last year’s lease was probably way over what he could afford too. He gets to stay in his apartment the government committees of the city in this county in the state, figure out a way and there are many cities with success stories like New York Santa Monica rent control. I’d be happy to discuss it, but in the meantime, he is grandfathered in and that’s it anybody else that has the lease ending June 1 or after that that is below 50,000 income their rent will be remain the same if they choose to stay.

So to me, that would be the beginning of the future of housing for all residence. Currently, we are going to do this first to protect those that are living here.

The consequences could be Dire. There are lots of great people who work hard and earn an “ok” income in comparison to six figures we can deal with that later, because the people that make six figures can afford to pay what they want to charge. It’s basically a form of rent control then we will deal with all the new housing which I kind of have a simple answer to that too but right now let’s take care of this guy because there are thousands of him and if he can’t afford it and he can’t find a new place then it’s gonna be a snowball effect because then he hast to leave medicine, and he has to quit his job as a contractor good worker, and the employer has to replace him and believe me will have to pay more probably than he’s even making just to do that. Let’s not let that happen but you can’t drag your feet. I think he stated it best when he said the problem is I’m stuck in the middle my income isn’t so low that they will give me some assistance right now, but it’s not enough to pay what they are demanding.

Thank you again for writing this article it’s very important. I will be sure to pass it along..

P.S. for example, In Chicago when investors build new apartment buildings, they must allocate, I believe it’s between 10 and 20% of their units for lower income..PERIOD! I believe in New York, the way they offset those expenses was their buildings that are Luxury highend apartments. They have more amenities in their building, then attached to the other building because they do share some things. There is 20% of good quality nice apartments I had a little bit lower value on the spectrum. I mean I’m telling you by time everybody gets done with this and does anything about it? What’s happening with the Oscar Meyer property that was going to be done? It’s still it’s gonna take time. So I’m just suggesting perhaps three or four categories.. let’s take this one first current residence to earn less than 50,000 a year

I got hit by a Madison Metro bus while walking in the crosswalk at Lake Street and Langdon Street. I talked to 3 different Madison law firms. No one wanted to take the case. Sounds like your accident may be your ticket.

The author lays out an accurate predicament of this economy. I’ve been involved in downtown Madison housing/apartment living for 35 years. An interesting “Longview”, in an effort to take out the “knee jerk” inclination to blame is that this problem is real, and this is a “non subjective” math problem.

Housing/rents and costs of multi family housing has realistically doubled in the past 17-20 years in downtown madison and those same rents and costs of producing and operating that housing has roughly tripled in 22-26 years. These numbers are not generally or overly controverted and for this purpose are within some reasonable range regardless of type of housing in Madison, including high end housing, suburban medium income and older more modest rents.

Understanding the cause is fairly straight forward. The resolution is less clear, but as a practical issue:

An average 2 bedroom apartment in Madison 8-10 years ago may have averaged $1000-$1300 and today that same apartment is $1700-$2600.

That same apartment at that time was assessed by the city at $120,000-$160,000 and today that same apartment is assessed at $200,000-$260,000.

With a Madison mil rate/tax rate of 2.1 %, the practical problem with rent costs and even the most well intended housing operator’s efforts to maintain costs is that the taxes for a basic 2 bedroom apartment have increased from $3,000/year to $5,000 per year in this same time period. Monthly, this means that property taxes for an average 2 bedroom apartment is now nearly $400/month and as a function of what might be considered a “target”/ desired rent for a modest $1200-$1300-$1400. $400 per month for taxes alone. Add water/sewer fee increases of 300%-400%, insurance costs more than doubling as well as heating/ maintenance costs doubling or tripling. These costs when combined would total 80% or more of those desired rents if they had been maintained stable. This 80% figure of operating costs includes nothing toward the cost of this “vital” asset or the impact of interest rate increases from 3.5 to 7% which will accelerate all these pressures immediately and will perhaps generate housing cost increase of an additional 20-30% in the next 2-3 years.

The cost side of this problem is reasonably effortless to quantify. Costs have doubled in 12-18 years. Wages for these types of jobs described have not. Landlords are perhaps the easiest target, yet as I have long maintained, the landlord/operator is in a position to control a “maximum” of 10-15% of these total costs. The resolution is far more complex and efforts to fix or control rents will exacerbate this issue. IZ was tried here and was a disaster. Controlling or limiting production will not improve the reality that people want to live here.

The point of my comments is that taxes alone of $400/month for an average 2 bedroom apartment and as much as $500/month for a newer high end 2 bedroom unit makes $1,300 workforce housing a “thing of the past” in Madison, Wisconsin.

Great Article. Thank you for writing this. It is the most critical unnecessary time that hopefully they will get an affordable housing clause in Madison. I am going through something similar. I pre-paid $10,000 with my rent and never been late never had a complaint. My stole was nearly 40 years old and it was going out and had bugs in it and I asked for a new one and she retaliated against me and said she was going to bring me the exact same one, they have downstairs and then he said they have two brand-new stoves, but the apartment manager decided to retaliate and try to give me a Stove. I also turned my hot water up conveniently when the maintenance man will leave it Friday at three and then magically it would come back on at 7 AM on Monday and many other issues. A whole apartment building is supposed to be non-smoking and I’ve complained a couple times because I have asthma real bad and so I’m the only one that she hasn’t renewed all her other smoking buddies. She renewed every single one of them. Also, the sliding glass door was defunct, check, tremendous amount of strength to open the store, and I tore my bicep and tricep, as They wouldn’t come and fix it. So I needed to call the building inspector, and they finally got it done. I’m taking them to court for retaliation. I have many other issues, the same type of thing where she just retaliates and it’s like what is their problem. I think I have a compelling case and I’m pretty sure that I’m gonna win. Make sure that this doesn’t ever happen to anybody else who exercises their right. Ty!

I recommend taking a deeper look at the issue mentioned in the article regarding there being a shortage of “luxury units” in Madison for renters making above 80% AMI. In reality, renters at these higher income levels have a broad range of housing choices. The housing market is not broken just because many higher income renters occupy market rate units where they can pay less than 30% of their income on rent.

I think a better approach to understanding where shortfalls are in the rental market is utilizing the approach taken by the National Low Income Housing Coalition, which looks at the number of units that are “affordable and available” to renters at different income tiers. Their calculation, which takes into consideration the number of affordable units that are not occupied by higher income households, provides a much clearer picture of where the gaps are in the market and where government intervention is needed. https://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/gap/Gap-Report_2022.pdf

One of the risks with utilizing “market shortfall” calculations like that utilized in Madison’s 2022 Housing Snapshot report is that it can contribute to a misunderstanding of where the most serious shortfalls are in the housing market. In many areas of the country, policymakers often rely on similar calculations to direct precious government resources away from subsidizing housing for the lowest income renters and towards subsidies for higher-end housing, where subsidies are typically not needed.

This article examines the failures of market rate development overwhelming the ability of the public and non-profit sectors to keep pace with growing income inequality. A state legislature that strangles local initiative and bows to corporate masters while limiting policy and funding options creates an institutional dynamic where people, especially African Americans, ultimately suffer in this community with poorer birth outcomes and a host of other factors.

Forcing communities to rely on property taxes perpetuates increasing inequities as apartments are actually taxed less than residential square footage while profiting greatly. Meanwhile federal tax laws inherently support speculative developers/landlords while the feeding frenzy continues.

A public bank or infrastructure fund offering no, or low rate loans to developers of permanent affordable housing is one critical step we need. Of course with limited vacant developable land, it is not the only thing needed.