An office building for KeyBank in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.An office building for KeyBank in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The bank is one of the nation’s largest, with 1,000-plus branches in 15 states. Photo by Flickr user Tony Webster, CC BY-SA 2.0

When large banks propose mergers, fair housing and lending advocates frequently try to block the deals. They say the transactions often result in branch closures, layoffs, and service cuts, and when there’s little banking competition in a particular area, banks often make less of an effort to offer products that meet the community’s needs.

So when KeyBank sought to acquire Buffalo-based First Niagara, which would make it one of the nation’s largest banks, it not only had to prove to banking regulators that the merger was sound, it also had to win over local and national advocates.

The result was a landmark agreement in 2016 that was expected to bring billions of dollars in investments to low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities. Dozens of community groups and the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC)—an association of 700-plus community-based organizations and lenders—had negotiated a $16.5 billion community benefits agreement with KeyBank executives, the largest at the time by a single bank.

Community benefits agreements, or CBAs, are agreements—ideally formal contracts—in which real estate developers and financial institutions promise to provide specific amenities to a community to get buy-in for a project.

“This is a new blueprint in how banks can work constructively with community groups and the NCRC specifically,” said Beth Mooney, then-CEO of KeyCorp, KeyBank’s parent organization, at the time.

Noting the lending, community investments, and philanthropy KeyBank promised in the CBA, the federal Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) approved the merger.

Now, more than six years later, NCRC alleges that KeyBank not only broke some of its promises, but actually regressed in the share of its lending that goes to LMI and Black communities. The CBA did not include targets for investments by race, but NCRC considers lending to Black borrowers a crucial indicator of a bank’s commitment to community reinvestment. NCRC publicly cut ties with KeyBank in December 2022, calling it “the nation’s worst major mortgage lender for Black homebuyers.”

According to an NCRC analysis, of the top 50 mortgage lenders in 2021, KeyBank ranked last in loans made to Black borrowers. Of the 46,971 home mortgage loans it originated, only 1,036—or 2.2 percent—included a Black applicant, compared to a range of 2.9 to 20.8 percent for other major lenders.

“KeyBank trailed most or all of its local competitors in shares of home lending to Black and LMI borrowers in most of the cities where it operates,” NCRC alleged in a scathing report. “KeyBank also appeared to engage in systemic redlining, making vanishingly few home purchase loans in neighborhoods where Black families were clustered. Inclusive home lending metrics indicate that the bank’s performance worsened each year since it promised community groups it would do the opposite.”

KeyBank disagrees with NCRC’s characterization. The bank says it fulfilled 50 of 53 commitments in the CBA by the end of 2021 and was on track to complete the remaining ones. It says its investments and philanthropy ended up amounting to $26.5 billion, far more than promised. However, the bank did not dispute the accuracy of NCRC’s data, which KeyBank itself provided to the government under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA). A bank spokesperson declined an interview request.

Who is responsible for evaluating whether promises made in a community benefits agreement are kept? Is there any recourse for community groups that don’t receive what they’ve been promised? And what lessons can we take away from the KeyBank CBA?

The KeyBank Agreement

Cleveland-based KeyBank is one of the nation’s largest banks, with 1,000-plus branches in 15 states, including New York. Because KeyBank’s and First Niagara’s service areas overlapped, the acquisition proposal tripped regulatory thresholds on competitiveness in Buffalo and several other markets.

“KeyBank agreed to work with NCRC and our members because they needed to show to their regulators that the merger was going to bring about enough of a positive benefit to the public that it would outweigh any anti-competitive effects,” says Kevin Hill, NCRC’s Community Reinvestment Act manager.

‘Three of the leadership at Key Bank we met with were Black. We talked about racism in very frank ways, which I know they don’t [do with] white people. And they got it. They got serving Black and brown people.’

Merger reviews also provide one of the few real enforcement mechanisms for the Community Reinvestment Act, or CRA. The 1977 law requires the OCC, FDIC, and Federal Reserve to encourage financial institutions to meet the credit needs of low- and moderate-income neighborhoods, and regulators can block mergers or branch openings, or pressure banks to improve if they have poor records of compliance.

In 2016 NCRC organized a series of meetings between KeyBank officials and members of two dozen groups from Maine, New York, Ohio, Oregon, and Pennsylvania. Mergers like KeyBank’s are a great opportunity to get banks to do a better job of serving their communities, says Ernie Hogan, executive director of the nonprofit Pittsburgh Community Reinvestment Group, which signed onto the CBA.

“A big part of our concern at the time was that First Niagara wasn’t really performing very well from a mortgage origination standpoint. They didn’t have a good first-time home mortgage product, or a product that really helped working-class and low-income people and people of color buy homes. And they didn’t have, in our opinion, a good presence of community reinvestment staff in Pittsburgh,” Hogan recalls.

“We want all our bank partners to be profitable and be productive, because that creates competition, it creates variety of products, it creates real opportunity for us to empower our working class and our residents and to get them on pathways to wealth-building,” he says.

Ruhi Maker, senior attorney at the Empire Justice Center in Rochester, an NCRC member organization, also participated. She and other advocates with decades of experience negotiating CBAs brought a wealth of data on their communities’ lending and investment needs to show KeyBank what it needed to do.

“We recognize that serving the low-income community, serving the Black and brown community, is not easy, and that what works in Rochester or even Buffalo may not work in Ohio, or vice versa,” Maker says. “I understood how they could meet their lending commitments: ‘Here’s how you’re going to meet your community credit needs. Here’s the first-time homebuyer program. Here’s what the underwriting needs look like. Here’s how you do outreach.’ I made sure that they were going to do right by Rochester.”

The advocates had very direct discussions with the executives, she says. “Three of the leadership at Key Bank we met with were Black. We talked about racism in very frank ways, which I know they don’t [do with] white people. And they got it. They got serving Black and brown people.”

Along with specific regional goals, KeyBank agreed to provide $5 billion in mortgage lending to low- and moderate-income communities over 5 years, $2.5 billion in small business lending to those communities, and $8.8 billion in community development lending and investment. The bank was to spend $175 million on charitable grants, $5 million to market its low- and moderate-income services, and $3 million on product innovation.

KeyBank also promised to end its payday lending business, keep certain branches open in low- and moderate-income areas, and create a national advisory committee with NCRC to monitor progress.

Hill says KeyBank refused to set specific goals for lending to individual racial groups or communities of color, claiming those rules would be legally problematic. Maker says she would have liked to get a “right of action” into the CBA, which would have allowed advocates to sue if KeyBank didn’t fulfill its terms. But overall, the group thought it was a strong plan.

“They came to Pittsburgh and we had a great meeting with the leadership at the time and the responsibility officer. Lots of promises were made, lots of resources started to flow,” Hogan says. “And then it kind of went dark.”

‘We can’t let the regulators use the CBA as a basis to approve a merger and then totally walk away when the bank doesn’t comply with them.’

Within a couple of years after the agreement was signed, NCRC saw signs that the bank’s commitment was wavering. Hill and Maker say KeyBank seemed reluctant to provide data demonstrating its compliance with the CBA. Hill says that at one point bank executives conceded they were having difficulty boosting mortgage lending to low- and moderate-income communities, as they had promised to do.

“They would usually just try to kind of brush those concerns under the rug and say they’ll figure it out, or something like that,” Hill recalls.

While the agreement was high-profile and the regulators relied upon it, it was not a legally binding contract. In addition, some of the wording would make it hard to hold the bank to account even if it were, such as “expects to invest up to 35 percent of that amount in the First Niagara/KeyBank footprint” (emphasis added), with no corresponding “at least” amount.

Following Through

In 2019 NCRC performed an analysis that showed KeyBank was not meeting its mortgage lending goals, Hill says, but the bank assured them it would do better.

It can be difficult to see trends in lending data, which only becomes available the year after the lending occurs and requires a time-consuming analysis. Maker says KeyBank would only provide merged data to national advisory committee council members and refused to separate it out by region.

“There’s an internal adage, at least among the bankers that I used to hang out with: if you don’t want to answer the direction directly, just drown them in bullshit,” says Horacio Mendez, a former banker and Federal Reserve staffer who heads the nonprofit Woodstock Institute. “Just flood them with data and see whether or not they can find it. Because the industry doesn’t want to make it too easy to connect the dots.”

In 2021 KeyBank surprised NCRC members by unilaterally announcing it was “extending” the CBA by committing an additional $22 billion to it. Hogan says because some of that is for internal bank initiatives, the actual amount of new money for communities—investments, grants, and other programs—will amount to $18 billion over an unspecified period of time. NCRC members met and came up with new priorities for the CBA, including race-based goals, which KeyBank again refused to accept, Hill says.

NCRC president Jesse Van Tol says his negotiating team “began to suspect bank leaders were stringing us along.” He asked the team to analyze KeyBank’s data, and eventually concluded KeyBank’s leadership team was “not sincere in their public claims about their bank’s commitment to economic equity.” Van Tol was appalled and quit the national advisory committee. n December 2022 NCRC released its report castigating KeyBank for its lending record.

KeyBank says it fulfilled most of its CBA commitments. And NCRC says the bank did end its payday lending business. But Hill says the misses include some of the most important pledges. The CBA envisioned 20 percent increases in low- and moderate-income mortgage lending in all of the bank’s markets, including former First Niagara markets. But according to HMDA data, KeyBank’s mortgage growth in Buffalo was significantly below 20 percent, Hill says. According to bank data, its LMI mortgage lending from 2017 to 2020 had a compound annual growth rate of 6 percent in Buffalo and just 2 percent in Rochester, he says.

In its response to the NCRC report, KeyBank said that from 2018 to 2021 it increased loans to Black borrowers by 24 percent and more than doubled its lending to all non-white groups.

NCRC says that number represents all types of loans, including mortgages for second homes, multifamily buildings, and investment properties, not just the crucial area of purchase lending for owner-occupied homes with one to four units. In addition, KeyBank had done little mortgage lending before the acquisition, so the increase doesn’t represent a large number of customers, Hill says.

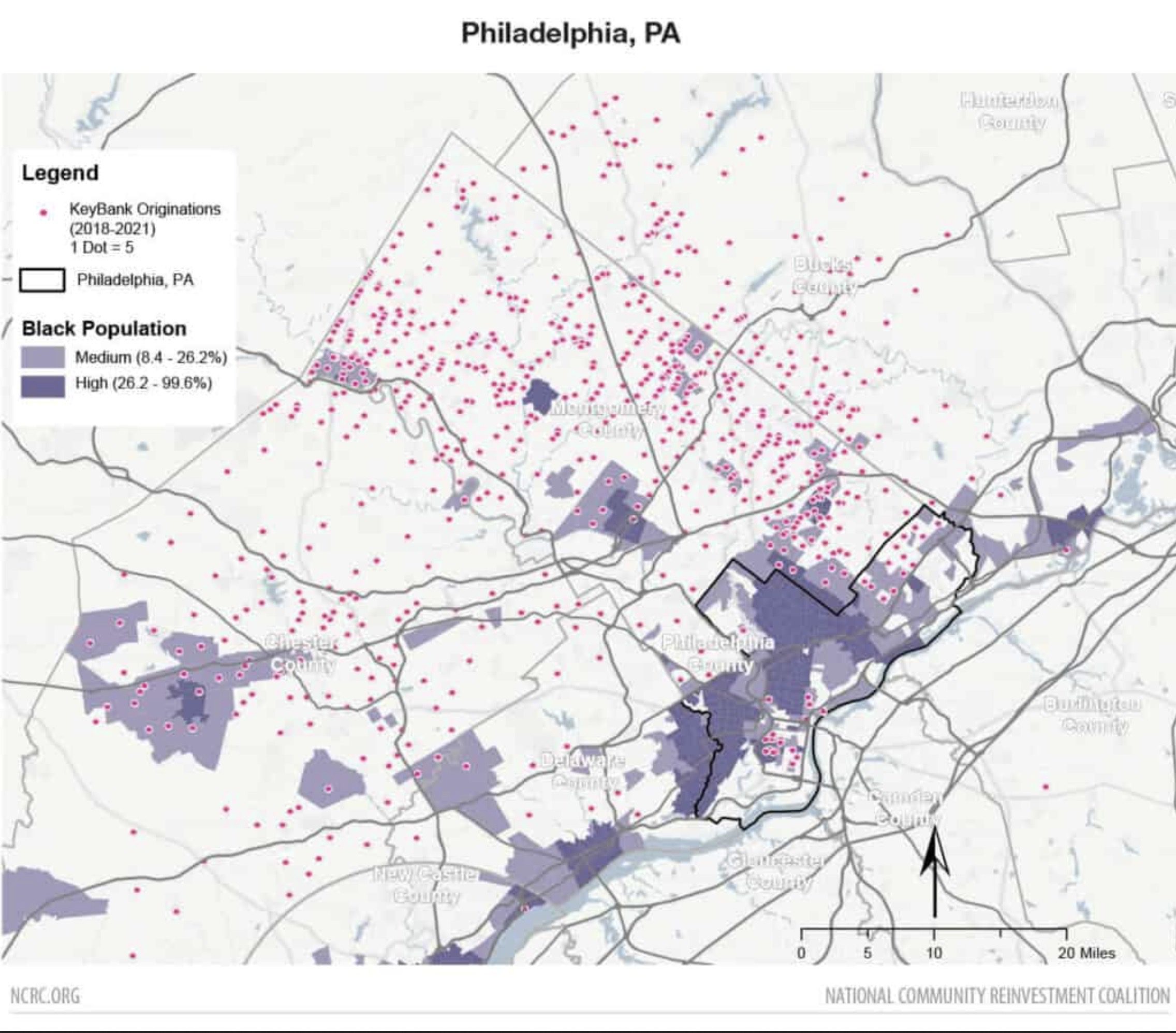

Map produced by NCRC

In fact, even as it ramped up its mortgage lending overall, KeyBank progressively reduced the share of its loans going to Black people in most of its markets, according to NCRC. The starkest example is the Philadelphia metro region, where about one-fifth of the population is Black. KeyBank’s already-minuscule home purchase lending to Black borrowers there fell 3 percent between 2018 and 2021, while for the city’s top 10 banks such lending increased 4 percent, according to NCRC.

In 2021 KeyBank originated 155 home purchase loans in Philadelphia, but only 2 of them had Black applicants, or 1.3 percent, NCRC’s report says. That compares to 14.4 percent for the city’s top 10 banks.

A map produced by NCRC shows that KeyBank effectively practiced redlining in Philadelphia, as it did in other places. Most of its home loans in 2021 went to borrowers in suburbs outside of Philadelphia proper, with just a few around the city center and almost none in areas with a high percentage of Black residents.

In Seattle, its biggest mortgage market, KeyBank did 2,184 mortgage originations, of which 8 had Black applicants, or 0.4 percent, compared to 1.8 percent for the top banks. In Buffalo, the second biggest market, 14 of 652 home loans went to Black people, or 2.1 percent, compared to 8.3 percent for the top banks.

Home lending to low- and moderate-income borrowers saw similar trends despite a specific pledge in the CBA to increase those loans, according to NCRC’s report. Over the four-year period, the share of KeyBank’s overall home purchase lending that went to LMI applicants plummeted by 23 percent in Seattle, 16 percent in Philadelphia, and 11 percent in Pittsburgh. In Denver, the top 10 banks increased the share of their lending to LMI applicants 8 percent over that period, but for KeyBank that share dropped 10 percent.

KeyBank says the proportion of its loans going to LMI customers has remained consistent. But that counts all types of loans and would still contravene its commitment to boost that measure of lending to LMI customers.

It is not entirely clear why KeyBank failed so dramatically to boost its share of mortgage lending in Black and low- and moderate-income communities. NCRC alleges that the bank seemed focused on profit-taking: after seeing big jumps in revenue due to the acquisition, it sharply increased its dividend payments to shareholders. Within a couple of years it saw the retirement of its relatively progressive CEO, Beth Mooney, and of its president of community development banking, Bruce Murphy, who is Black, and KeyBank Foundation CEO Margot Copeland.

Hogan says half of the bank’s CRA team left, as did the regional president in Pittsburgh. He says he knows a KeyBank loan originator who quit because it was difficult to get the bank to approve competitive new loan products. In Pittsburgh the acquisition had given KeyBank the remnants of a local bank that had never properly developed its mortgage business, and the new management never fixed its operations to address local needs, he says.

“Instead of getting that high-level talent that they needed to turn the system around, they just promoted from within,” Hogan says. “I still think they haven’t figured out how to recover the mortgage company to be that competitive, progressive, market-sensitive, product-based system with good talent.”

KeyBank’s grant funding as part of the CBA did make a big difference to organizations like the Pittsburgh nonprofit Neighborhood Allies. In 2018 the KeyBank Foundation awarded the group $300,000 to support its Upper Hill District Healthy Neighborhood Action Plan, and in 2021 it gave another $400,000 to support a suite of economic opportunity programs, including investment clubs for Black women, youth banking initiatives, and financial counseling for Black entrepreneurs and emergency rental assistance recipients.

“Large multi-year grants are pretty rare,” says Sarah Dieleman Perry, Neighborhood Allies’ director of economic opportunity. “But they’re also necessary for us to spend time on actually growing the programs rather than chasing $5,000 and $10,000 grants.”

Yet Perry says KeyBank’s donations do not let it off the hook for its other commitments. “They need to do both,” she says. “They need to be supporting nonprofits that are doing important work that has an impact in these communities, and they need to be providing mortgages and loans and opportunities directly to people of color in these communities as well. So it’s good that NCRC is holding them accountable.”

Stronger Requirements, Stronger Enforcement

Since the KeyBank agreement went into effect in 2017, NCRC has negotiated more than 20 such CBAs totaling more than $550 billion—the most recent is a $50 billion community benefits agreement with TD Bank. And none have “right of action” or enforceability clause, which allow advocates to sue if the terms of the CBA are not fulfilled. Hill and other experts say most banks are much better than KeyBank about following through on agreements, and they still believe CBAs are an essential tool to hold banks accountable and boost financial services and investments in disadvantaged communities.

But they say the KeyBank episode illustrates the continuing cost of federal regulators’ refusal to enforce community-benefits commitments, or to use the Community Reinvestment Act or other powers to sanction financial institutions that violate their obligations to serve LMI customers.

“We don’t need new rules. We don’t need new laws. We just have to do a better job with what we’ve got. That would make a hell of a difference,” says Mendez of the Woodstock Institute. “I’m all for CBAs, (but) I’m reluctantly for them, because we don’t have anything better. And that’s heartbreaking.”

The experience with KeyBank shows that negotiators must insist on incorporating very specific data reporting requirements and deadlines into agreements, advocates say. “We still have a lot to learn, and a fair amount of things we keep improving upon as we do more of these,” Hogan says. Hill says KeyBank’s refusal to accept data reporting requirements in an extended CBA contributed to NCRC’s decision to pull out of negotiations.

But Hill, Hogan, and others also lay the blame for weak or unsuccessful CBAs at the feet of federal regulators. The OCC approvingly cited the CBA in its approval of the First Niagara acquisition and in a subsequent CRA exam, but never did any follow-up to see whether KeyBank was fulfilling its commitments.

“The regulators need to link this process a little bit more,” Hill says. “There should be a review a couple of months later to make sure that the bank followed the things that they said they would do, but we would argue too that that should be factored into their CRA performance.”

That is, when HMDA data shows a bank hasn’t met its CBA commitments, it should be at risk of receiving a “Needs to Improve” or “Substantial Non-Compliance” CRA rating, which can harm the bank’s reputation and bar it from opening branches or merging. (The OCC gave KeyBank its ninth consecutive “Outstanding” rating in 2018.)

“We can’t let the regulators use the CBA as a basis to approve a merger and then totally walk away when the bank doesn’t comply with them, which seems to be the current situation,” says Matthew Lee, executive director of the investigative organization Inner City Press and an NCRC board member.

An OCC spokesperson declined to comment on KeyBank or the CRA rating process. She provided links to a recent speech by an OCC official on its efforts to promote fair lending, and an announcement of an enforcement action by the agency. In 2021 the OCC fined Cadence Bank $3 million for engaging in redlining in predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods in the Houston area. Under a related Department of Justice settlement the bank agreed to invest over $5.5 million to increase credit opportunities for residents of those neighborhoods.

Mendez says there is precedent for a more robust regulatory response. In the 1990s, when he worked at the Fed, the regulator itself would give conditional approvals for some mergers and require the banks to provide quarterly updates on their compliance, he says.

After the regulatory environment shifted in the early 2000s, the Fed stopped monitoring post-merger performance, and third-party CBAs like the KeyBank plan became more common, Mendez says. Those only last three to five years and aren’t legally enforceable the way a regulatory agreement is. Regulators could insert the CBAs into merger approval conditions and order banks to report their progress, but as long as they don’t, “CBAs are background noise” for the banks, he says.

“There’s no real tangible repercussions other than maybe some bad media. Nobody’s going to close their account at KeyBank because of this. They’re not going to lose any business. Community benefits agreements seem to be a little bit of a consolation prize,” Mendez says. KeyBank had $7.3 billion in revenue and $2.6 billion in net income in 2021, up from $6.3 billion in revenue and $1.3 billion in income in 2017, according to the company’s annual report.

Still, Mendez supports the use of CBAs as “really kind of the only tool we have.” He says he applauds NCRC for serving as one of the few organizations in the country with the resources to monitor CBAs, since relying on small, poorly funded nonprofits like Woodstock would almost guarantee more failures like KeyBank’s.

“In moments like this, where we need somebody with stature, with media presence and with resources to be able to say, ‘you’re breaking a promise you made to us,’ it really has to be NCRC,” Mendez says. “When I need a three-ton gorilla to show up with a lot of resources behind them and their heart in the right place with the same mission that I have, NCRC and Jesse Van Tol and his team are my guys.”

Comments