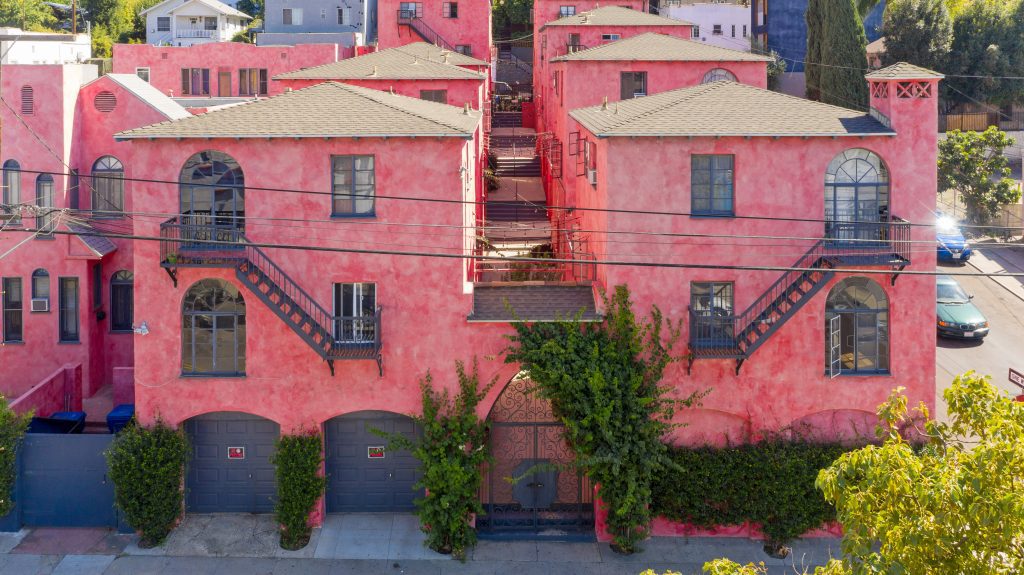

A rent-stabilized apartment building in the Echo Park neighborhood of Los Angeles. Photo courtesy of Nico

Neighborhood “revitalization” and “transformation” are on the tip of the tongue in communities across the country. For some, terms like this conjure flashbacks to an era of urban renewal; for others, they imply progress and profits. When a neighborhood undergoes redevelopment, it is typically private real-estate investors who reap the profits, while the ensuing rise in costs of living can make it difficult for longtime residents to stay.

But what if we designed investments in neighborhoods harmed by institutional marginalization and extraction in ways that let community members and local institutions participate in wealth creation and decision-making power? Wealth-building historically has focused on helping people own the home they live in, but these new models are helping residents and nonprofits own a slice of their local shopping centers, apartment buildings, and other properties.

A new set of projects across the United States is underway to broaden who owns and controls neighborhood real estate. These projects are contesting the status quo of real estate investments that may bring new housing or jobs to an area but seldom give community members or institutions a say in development decisions nor a share of the profits.

These projects are creating opportunities for residents and community-based organizations (CBOs) to participate as owners in their local economy, to share in the benefits of real estate development and business finance, and to build wealth. And beyond wealth, such control can help bolster other important social and economic outcomes such as job creation, environmental sustainability, transit connectivity, and improvements in health. These projects are making room for community members to have a say in what form of neighborhood economic development they want.

From our analysis of the landscape, we classify emerging local community wealth-building projects into four categories. Proponents of equitable community development can and do design local projects that blend these models together to meet their community’s distinct needs and goals—they are not mutually exclusive.

Neighborhood Crowdfunding: Individual community members have fractional ownership or a small stake in an income-producing business or property.

Neighborhood Crowdfunding

Unlike most commercial investment opportunities, Neighborhood Crowdfunding models are available to community members with lower incomes or net worth (nonaccredited investors) who do not typically profit from real estate development or small business finance. Some projects go beyond inviting residents to participate in the project’s financing and also invite them to function in a governing role.

Neighborhood Crowdfunding models go by many names. There are neighborhood real estate investment trusts such as Nico where local investors collectively own a portfolio of local properties; investment cooperatives such as the NorthEast Investment Cooperative where Minnesota residents collectively buy, rehab, and manage properties; democratic investment funds such as The Boston Ujima Project where a community-governed source of capital lends to small businesses owned by people of color; and community investment trusts.

Most models require investors to live within a certain geographic area. Investment sizes and frequencies vary. Sometimes investors make only a one-time investment, while other projects call for small monthly contributions with minimum investments as low as $10 a month.

An early prototype in the Neighborhood Crowdfunding space was Market Creek Plaza— the first of its kind Community Development Initial Public Offering of shares in a San Diego commercial plaza that occurred in 2007. The original vision from The Jacobs Center for Neighborhood Innovation imagined community members managing a development business that would invest a portion of the plaza’s profits in additional development opportunities. But not all aspects of the original vision materialized and the effort was not profitable. Market Creek offers an instructive example: to create wealth for resident-owners and keep money in neighborhoods, retail projects must be financially viable, be able to face economic uncertainties, and be in a location that attracts a wide set of customers. The Jacobs Center for Neighborhood Innovation has since embarked on an effort to better understand the Diamond neighborhoods growth potential.

More recent examples, such as the East Portland Community Investment Trust where residents from four Southeast Portland ZIP codes jointly own a commercial retail plaza, have performed well, demonstrating the viability of the neighborhood crowdfunding approach. Plaza 122 serves a dense, family-friendly residential area where two thirds of the residents are renters. Before the sponsor entity, Mercy Corps, purchased Plaza 122 along with two private investors in 2015, they asked residents what amenities their neighborhood needed, what they desired in a financial product, and considered what was feasible. Now, Southeast Portland residents of all economic classes can invest in the property at investment levels between $10 and $100 a month and have the flexibility to cash out if needed. Residents will eventually buy out the original investors completely. In 2019, over 160 invested families received three rounds of dividends averaging 9.3 percent, and all but one retail tenant consistently met rent even through the economic difficulties posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

An even more recent example is The Guild, a community organization in southwest Atlanta that has a vision to close Atlanta’s racial wealth gap. This vision is being actualized through the purchase and redevelopment of a prime piece of real estate in the Capital View neighborhood where 18 to 20 affordable rental units, a locally sourced grocery store, and shared kitchen space for emerging Black restaurateurs are being built. The Guild formed a community real estate trust to give residents a piece of the value. Anyone in the building’s ZIP code can invest $10 to $100 a month in shares of the trust—an investment in a property that is expected to appreciate over time—and investors will receive annual dividends as well as voting rights.

Occupant Equity

When groups of community members in areas with rising property values pool their resources or source funding from the philanthropic and public sectors to buy real estate, the property can be converted into long-term affordable housing, commercial, or agricultural space with stabilized units for purchase. Although the returns that occupying residents and businesses earn on the sales of their property shares are modest (they’re sold at a capped amount determined by a formula), this is what makes units affordable for the next occupants, who would otherwise be priced out. Occupant Equity projects attempt to balance the immediate need for affordable real estate and the longer-term need for wealth building. Affordability preservation is most successful when a government or philanthropic subsidy is present.

Organizations that employ the Occupant Equity model either use a nonprofit structure, such as the community land trusts (CLTs) or limited equity cooperatives. The traditional governance structure of a CLT includes tenants who live in properties on CLT-owned land, community members, and community development practitioners, all of whom vote on key decisions.

In the historically disinvested and rapidly gentrifying neighborhood of Oakland, California, community members banded together to form the East Bay Permanent Real Estate Cooperative (East Bay) which combines the Occupant Equity and the Neighborhood Crowdfunding models. In East Bay, community residents (“member owners”) work together to identify properties for acquisition (e.g., abandoned properties, properties at risk of being sold to speculative investors, etc.). They pool investments from individuals who buy East Bay shares (“investor owners”), raise capital from external funders, and secure loans to purchase properties to which the cooperative entity holds the titles. This arrangement provides a modest return (1.5 percent) to investor owners and creates affordable housing for current and future residents.

Local Institutional Equity

Wealth can be created for local institutions, not just residents. Commercial ownership stakes held by community-based organizations expand possibilities for CBOs to serve their communities by creating ongoing cash flows that can be used for future community investment and programming. Sometimes mission-oriented investors or philanthropies provide grants or highly subsidized loans to CBOs to help institutions increase their stakes in and improve the economics of investments in ways that allow institutions to earn returns on investments sooner.

A Local Institutional Equity model had clear benefits in the Auburn Gresham neighborhood of Chicago where three organizations—the Greater Auburn-Gresham Development Corporation (GAGDC), Green Era, and Urban Growers Collective—completed the Always Growing Auburn Gresham (AGAG) project. The AGAG project—which in August 2020 was awarded the $10 million Chicago Prize 2020 from the Pritzker Traubert Foundation—constructed a federally qualified health center and pharmacy in one of Chicago’s most medically underserved areas; retail space, including a coffee shop, restaurant, and bank; an anerobic digestor generating renewable energy; and an urban farm, all of which built community assets in the neighborhood. The Chicago Prize 2020 allowed GAGDC to purchase an equity share in the for-profit digestor, meaning future profits will flow to the CDC to support neighborhood development. The investment is already attracting foot traffic and has catalyzed more investment in the Auburn Gresham neighborhood where another mixed-use development is planned and a new Metra station has broken ground.

A different approach was taken in Washington, D.C., where Whitman-Walker, a community-based health care provider, found a way to leverage the rapidly appreciating value of its land on 14th Street NW not by selling it but by redeveloping its flagship clinic into a mixed-use development through a joint venture with Fivesquares Development. Whitman-Walker placed 70 percent of the land’s value into the joint venture, proceeds from which serve as a stable source of revenue to support its mission. The other 30 percent of the value was liquidated. This approach enabled Whitman-Walker to diversify its investment strategy, receive what amounts to an annuity of a few million dollars, pay off debt, and begin planning for an expansion of its services to clients east of the Anacostia River.

In both Local Institutional Equity model examples, some of the success can be attributed to the presence of a strong and trusted anchor institution, resources available to invest, and to financially viable long-term investment prospects (a strong business in the anaerobic digestor operation for GAGDC and desirable real estate for Whitman-Walker).

Neighborhood Nonprofit Trust or Endowment

A final approach, the Neighborhood Nonprofit Trust or Endowment model, creates protected pools of collective equity and gives residents control over how this equity is invested to meet their needs. Generally, this approach is successful when there is an availability of long-term, low-interest capital and a commitment to centering community voices in their processes and governance structures. Some of these models are still forming, such as the Community Equity Endowment approach that essentially uses profits from partial ownership of major real estate property to create a local foundation that residents can control to provide small grants to fund local needs.

The Kensington Corridor Trust in northwest Philadelphia, where demand for land and real estate is on the rise, is a budding example of this model. The trust acquired 11 vacant properties along a 1.4-mile stretch and aims to buy 5 properties a year using long-term patient capital from philanthropic foundations to fund acquisition and redevelopment. The Kensington Corridor Trust, currently a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, is in the process of forming a perpetual purpose trust into which current and future real estate assets will be transferred to be used in accordance with the trust’s purpose; it is governed by a resident-led stewardship committee.

Trust Neighborhoods is also working to acquire properties in neighborhoods where existing residents are threatened by rising rents. The organization obtains abandoned properties with equity funding or bank debt and renovates it as mixed-income rental housing. Then, real estate is placed in Mixed-Income Neighborhood Trusts (MINTs) which are based on the perpetual purpose trust legal model, by which MINTs are legally mandated to both preserve affordability and generate profits. After properties are rehabilitated, some rental rates are stabilized at today’s naturally occurring affordable rates while others are floated at market rates, which helps preserve affordability and build wealth. To date, Trust Neighborhoods has launched MINTs in Kansas City and Tulsa. Community residents make up the oversight committees.

Community Wealth-building Projects are Worth Tracking and Supporting

These novel approaches to community wealth-and-ownership-building are just a few of the emerging ways that communities are responding to the rising demand for urban land and costs of living that are squeezing long-term residents. It is still too early to say whether many of these projects have been successful and it will be important to track their progress to observe their full set of benefits—financial and beyond. But already these examples offer lessons for community organizers, philanthropies, and housing and community development government agencies interested in implementing and/or supporting community wealth-building projects.

Many of the projects that build individual, institutional, and community wealth are made possible through intentional collaborations and the willingness of philanthropies to provide flexible, patient capital. Subsidies from the philanthropic or government sectors play an important role in accommodating atypical mixtures of investors while leveraging mainstream capital and new investments for the long term. Sometimes this looks like philanthropies taking on more risk, structuring loans with longer-than-usual repayment schedules or accepting below market rates of return on investment.

Breaking the investment mold to center on community wealth-building is not easy. It requires a combination of clearly defined objectives, motivated community stakeholders, dedicated partners, good communicators, savvy but socially minded financiers, and ripe opportunities. Even philanthropies have limited capacity to participate in bespoke transactions. Homing in on replicable financing solutions and standardized models that also provide the flexibility to match unique neighborhood contexts, project goals, timing, and capital needs will be critical. Lenders will need to understand these models, and the field more broadly will need infrastructure, institutional education, shared technology, and consumer education tools.

Local, and to some extent, state or federal governments, can do much to advance community wealth-building models by reducing legal barriers to accessing resources and by providing legal protections for the local residents and organizations involved. For example, community wealth-building projects often face difficulty in competing with private market buyers for land. Local, state, and federal policymakers can support these projects through implementing policies that enable projects to obtain real estate at low or no cost through off-market transactions. Governments have done this by passing right-of-first-refusal legislation, prioritizing public land sales to community wealth-building projects, and by strategically using land banks.

Governments can also pass legislation that expands projects’ capacity to raise capital. California’s legislature passed AB 569 and AB 816, which made it easier for housing cooperatives to raise capital by raising the maximum share price and by rolling back burdensome administrative requirements. Other avenues policymakers can pursue to augment projects’ capital-raising capacity include creating tax credits and amending community benefits requirements. Creating a hospitable policy environment for community wealth-building projects requires sustained collaboration between policymakers and project organizers. Specifically, policymakers should be tuned in to the challenges project organizers are facing and contribute their legal expertise to design creative policy solutions. And project organizers should organize their community base to provide testimonials and lobby policymakers to ensure these policies are passed.

When the right partners are brought together, a locality’s policies are sufficiently supportive, and projects are successful, community wealth-building models contribute to the revitalization and transformation of neighborhoods in ways that engage community members and involve them in local decisions. For many of the examples we cite above, only the future can say whether these models will meaningfully build wealth, improve wellbeing, and ensure community control. But early examples have demonstrated positive outcomes and newer models are making progress. Still in their early days, the success of these models is dependent on the support they receive from other actors in the environment. Investors, philanthropists, and policymakers who are on the fence should get their feet wet. And developers, lawyers, advocates, resident associations, researchers, and others with relevant expertise should assist. With support, these models can catalyze community development in a way that enables residents to prosper in place.

Cities should step forward and offer technical assistance to assist communities in their efforts. So much time and effort is spent by novice volunteer efforts to reinvent success on a project-by-project basis. It takes a special type of planner who knows both local conditions, political turf, development expertise and finances, to be an asset to projects rather than just a reviewer of proposals. Knowledge of on-the-street reality of each project and a passion for translating wishes into the successes the community wants. And an overall passion for neighborhoods as the driver in the city’s strongly stated vision is critical.

The Kataly Foundation and Surdna Foundation are supporting some exciting work in this space, as is my employer (The Kresge Foundation). It’s great to see some of our community partners highlighted in this article, such as Boston Ujima Project, East Bay PREC and The Guild Collective. More research is needed to show which models show the most promise in what sorts of local market and policy contexts, but it’s encouraging to see folks experiment with novel models of community ownership.