Photo by flickr user Chris Freeland, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Helene Caloir runs LISC’s New York State Housing Stabilization Fund and Mona Mangat directs the organization’s safety and justice programming.

Vacant, neglected buildings and abandoned lots shrouded in overgrown shrubbery are hard on neighborhoods, and people. They provide cover for activities such as vandalism and drug dealing, and create a sense of insecurity in a community. Reams of research, not to mention neighborhood experience, have shown that concentrations of vacant and deteriorated buildings tend to be hotspots for crime; one study looking at Cleveland tracked higher rates of homicide, weapons violations, and aggravated assault associated with vacant homes and lots.

As community development professionals, we also know that we must mobilize now against the wave of vacancies that, without unprecedented federal action, are likely to follow mass evictions and foreclosures related to the COVID-19 pandemic. This, too, will disproportionately harm communities of color.

Many observers think about vacant buildings and crime as two separate problems. But they are intimately connected and rectifying each requires a multi-pronged approach. Combining vacancy prevention and remediation with community safety programming is an effective combination for helping communities tackle existing issues of crime and vacancy in neighborhoods, and doing so has supported them in staving off future dislocations that threaten to create new swaths of vacant homes.

We have seen—and a substantial body of research shows—that crime tends to be hyperlocal, attaching stubbornly to certain “micro places.” A few hot spots, often that empty house or unmaintained corner lot, may generate the bulk of the crime in a neighborhood. Pinpointing interventions at those sites can produce outsize results.

In New York State, we have coupled this broader strategy with an anti-vacancy initiative—LISC’s New York State Housing Stabilization Fund, which was founded with funds from a bank settlement with the New York Attorney General’s office to mitigate the continuing effects of vacancies across the state following the 2008-2010 foreclosure crisis.

LISC, the Local Initiatives Support Corporation, is a CDFI that works with residents and partners to catalyze opportunity in communities across the country. The Housing Stabilization Fund supports multilayered partnerships between local governments and communities to inventory and track vacant properties (particularly those caught in foreclosure limbo, aka “zombies”), improve code enforcement, and ultimately revitalize these properties, bringing them back into productive use. The fund also supports counseling for at-risk homeowners to prevent foreclosures and vacancies from occurring in the first place.

[Related Series: Vacancy—How to Fight the Problem, What’s Working and Where, the Health Effect, and How to Get Residents Involved]

Because crime reduction and vacancy prevention and remediation go hand in hand, the goals of these initiatives are closely aligned, and so are their methods. The three strategies that follow are core elements of the methods we’ve used, and while they refer to work done by our organization, they are applicable to communities all across the country that are struggling to revitalize, reduce crime, and create strong, stable neighborhoods. We believe they will be all the more instructive as localities work to emerge from the devastation of the pandemic.

- Root the work in locally led coalitions that engage residents. Our community safety and justice projects rely heavily on the community-based nonprofits whose very presence in a locale leads to significant reductions in violent and property crimes. Residents participate by giving and gathering information, identifying priorities, and helping to carry out the strategies they have helped devise. The NYS Housing Stabilization Fund programs encourage collaboration across municipal agencies, along with outreach to residents and nonprofits, that helps the agencies identify troublesome properties and help set priorities for reuse.

- The work should be data-driven. If we don’t understand the sources of a problem, it’s hard to solve it. Safety teams design interventions to address crime based on police data—calls for service, incidents, etc.—as well as site observations, resident surveys, and stakeholder interviews. Local governments that have received grants from the NYS Housing Stabilization Fund develop data-management technologies and gather in-depth information from a variety of sources on properties’ ownership, tax and lien status, and condition, as well as police, fire, and sanitation department visits.

- Identify a “point person” to coordinate the effort. In projects that involve a diverse coalition of residents, community-based organizations, government departments, and researchers, it’s important to have a coordinator who can communicate with partners, call meetings, set a timeline, track progress, and keep the effort moving forward.

To see what this approach look likes in action, we can point to Flint, Michigan, and Binghamton, New York, just two of the many places that have applied these strategies with transformative results.

Community partner meeting at Kettering University in Flint, Michigan. Photo courtesy of LISC

With a $1 million grant from the U.S. Department of Justice and technical assistance from LISC, a coalition led by Kettering University took on a project to reduce violence and property crimes in the vicinity of Kettering’s campus in Flint, a city battered by depopulation and hit especially hard by the Great Recession of 2008-09. Four crime hot spots were identified through crime data analysis and community stakeholder input (area residents served on the project’s steering committee and various subcommittees). This process was led by the project coordinator, a researcher and seasoned community organizer at Kettering University, in partnership with the project’s research team. With the local police department severely understaffed due to the same forces that affected the city, the coalition knew that putting more cops on the ground was not in the cards, nor was it necessarily the right approach. Instead, teams of residents, organized through trusted local groups such as Carriage Town Ministries and the Flint Urban Safety Corps, cleaned up trash-strewn lots and installed LED lights on vacant homes. They cut back trees and shrubbery to create open sightlines. The university began acquiring abandoned buildings to turn them over for positive uses. The project supported a 78 percent reduction in the number of vacant properties in the focused neighborhoods, and according to data reported to the Department of Justice as part of grant deliverables, between 2013 and 2017—without increased policing—the entire University Avenue corridor recorded an impressive 49 percent decrease in assaults, 53 percent decrease in robberies, 78 percent reduction in burglaries, and 55 percent decline in vandalism.

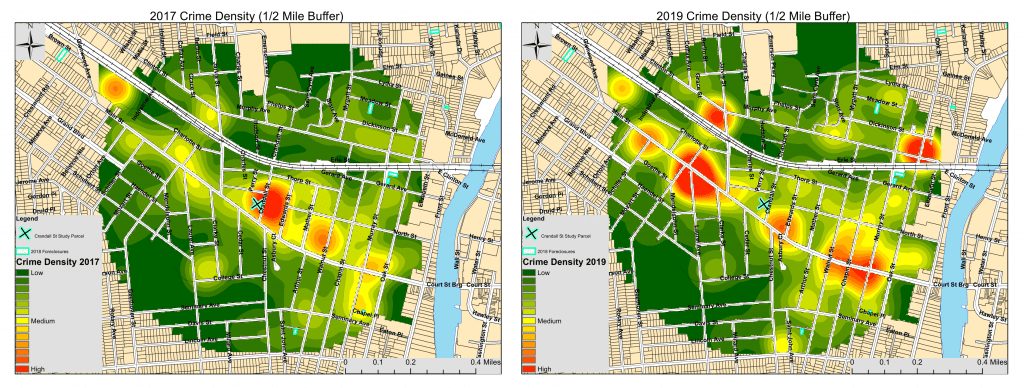

Heat maps measuring crime in a Binghamton, New York, neighborhood before and after building rehabilitation was done. The site that underwent rehabilitation is marked by a cyan X. The maps indicate an increase in crime in nearby blocks after rehabilitation was complete. There are many factors that may have attributed to this shift, but partners involved in the program, including police, attribute it in part to the fact that community engagement efforts may have encouraged more people to begin reporting crimes on certain blocks than they had previously. Photos courtesy of LISC

The City of Binghamton, meanwhile, its neighborhoods affected by many of the same issues as Flint’s, has made the remediation of vacant property a top priority since 2016. With a $250,000 grant from LISC’s Housing Stabilization Fund and technical assistance to address vacant and “zombie” properties, Binghamton was able to implement a program called BuildingBlocks that aggregates data and creates heat maps from multiple municipal resources including code enforcement, building permit records, and fire, police, tax, and housing records. This helped the city and its nonprofit partners (the group’s point person heads Binghamton’s department of planning) to inventory and analyze its vacant properties so they could focus limited resources strategically. Taking into account crime data, the number of vacant properties in a given area, property devaluation, and residents’ perceptions of their neighborhoods, among other factors, the city chose buildings to remediate and has since brought more than a dozen buildings back to productive use and the tax rolls. Those same heat maps now show decreases in crime and incidence of fires in the area that was once dominated by vacant homes.

It is important to note, however, that the maps also indicate an increase in crime in nearby blocks. The site that underwent rehabilitation is marked by a cyan X. There are many factors that may have attributed to this shift, but partners involved in the program, including police, attribute it in part to the fact that community engagement efforts may have encouraged more people to begin reporting crimes on certain blocks than they had previously.

In both Flint and Binghamton, millions of dollars were ultimately leveraged to create substantial improvements in the cities’ built environment, and in quality of life for residents.

But much smaller incremental investments can make a difference, too. A recent randomized controlled trial in Philadelphia found that just cleaning, grading, and greening vacant lots led to a 29 percent reduction in nearby gun violence compared with untreated control lots. People living near the improved lots reported feeling safer and using outside spaces more frequently to relax or exercise.

And as we have seen, when deeply rooted community groups and local anchor institutions are involved in such initiatives, they tend to accrue benefits while preventing unwanted consequences like over-policing and gentrification.

The evidence is there. We have the tools. What’s needed is an all-out effort by private and public actors to scale this under-recognized approach, allowing communities all across the country to lead their own rejuvenation and find their way to peace and safety. With a massive recovery ahead of us, the time is now. Let’s get to work.

This piece is exactly the ray of light I was looking for. My family has a business idea that will seek to work with community, local, state and federal stakeholders across the country in every state to bring a sense of urgency, interest, excitement, prosperity, pride and community back to economically disadvantaged black/brown communities. Our plan will address some of the challenges our communities have faced since slavery ended. Our project is not an end all be all to the problems facing the poorest communities in the country. The project attempts to address issues of racial discrimination in employment, economic inequality, food desserts in low income communities and some of the problems mentioned in this piece that our communities of color are victims of. Thank you kindly for the contribution!

Great idea Charlene. I am seeking to find the same type of approach to address a growing intergenerational poverty issue in Indianapolis. Have you had much success in generating interest from all of the various parties that could, and should, be engaged? I would appreciate the opportunity to talk further about progress made and frustrations we have encountered. Thanks, and good luck!