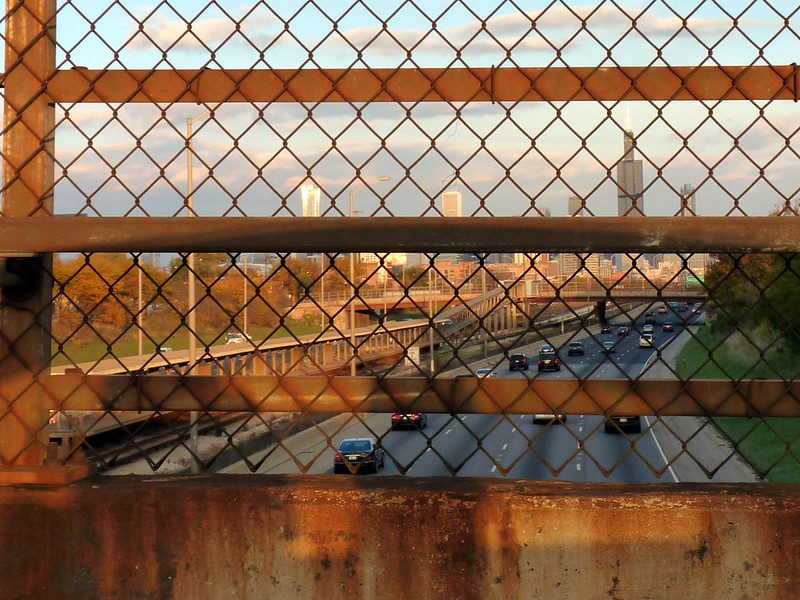

Photo by yooperann via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

With the onset of COVID-19 in March, jurisdictions across the country began introducing eviction moratoriums to prevent the immediate displacement of renters at risk of being made homeless due to job loss. Despite the persistence of the pandemic and the continued state of job loss impacting the economy, many of these moratoriums are set to expire over the next several months, placing the U.S. on the brink of an eviction crisis that advocates say will impact millions of lives. Despite recent federal action that may extend protections for a subset of renters into the foreseeable future, households now thousands of dollars behind on rent are still at risk of displacement at any time.

In Cook County, Illinois, an eviction moratorium was put in place on March 13, followed by Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s statewide executive order halting evictions on April 23. Despite these measures, tenants’ groups have still kept count of hundreds of eviction filings in the city of Chicago, with a recent Chicago Tribune article noting that landlords filed more than 3,300 evictions cases between March and August. Autonomous Tenants’ Union, which organizes renters facing displacement from the gentrifying Albany Park neighborhood, created a Wall of Shame to highlight the landlords most responsible for attempting to displace their residents during the pandemic, in addition to picketing specific landlords accused of illegally locking out their tenants. While some landlords blamed computerized systems for automatically filing evictions in Cook County’s eviction system, ATU organizer Antonio Gutierrez said that the filings still represented the uneven playing field facing renters.

“Putting an eviction on someone’s record is going to put another burden on them on top of being in the midst of a pandemic,” Gutierrez said. “The system and the courts are there to protect the interests of landlords and private property while diminishing tenants’ protections, including those put in place by Gov. Pritzker.”

Before the pandemic hit, Chicago’s rental population experienced an average of 23,466 eviction filings a year. Sixty percent of those filings resulted in eviction orders, according to the Lawyers’ Committee for Better Housing, an organization that provides legal representation to renters and tracks city eviction data (Note: the author was previously a policy intern at LCBH). The Lawyers’ Committee estimates that about one-fourth of the city’s evictions are no-fault, which are evictions where tenants are not behind on rent or have not created other issues in the building. This is causing disruption to thousands of households annually. In many cases, even the threat of an eviction filing is enough to push long-term renters out of their homes in gentrifying areas, a wave of “invisible evictions” that’s just as challenging to tenants and their communities.

Recognizing the harmful consequences of such no-fault evictions and lease nonrenewals, a coalition of nearly 40 housing and community organizations called the Chicago Housing Justice League [CHJL] has proposed a “Just Cause for Eviction” ordinance in the city. While CHJL had been in negotiations with the city’s Department of Housing (DOH) since last year, discussions stalled in early March, just before the pandemic struck. Now, with anxiety growing for many households behind on rent or mortgage payments, the need for increased protections has grown, a challenge that the city, like jurisdictions across the country, is struggling to meet.

“COVID-19 has exacerbated Chicago’s housing crisis, but it did not create it,” the Department of Housing said in a statement. “The role of the City of Chicago is to use public policy and public resources to balance and shape these forces and make housing a stable and affordable foundation for a high quality of life in every neighborhood.”

“Just cause” is a legal framework that requires landlords to provide sufficient grounds for any attempt to remove a tenant from through eviction, including nonpayment of rent, illegal activity, damage to the property, or a desire to move a relative into the unit. Landlords must prove their case in eviction court, a standard which could still prove challenging for renters: as of 2019, just over 1 in 10 renters had legal representation, a product of high costs, language barriers, and a lack of knowledge about their legal rights. Currently in use in some capacity in four states and over 20 cities, as well as covering all public housing and other federally subsidized housing nationwide, just cause shields tenants from being forced from their homes without justification. Tenants are often given only a month’s notice, and the eviction potentially puts an eviction notice on their record that will cause significant housing instability thereafter.

[RELATED: Eviction Filings Hurt Tenants, Even If They Win]

While details are still being negotiated, current proposals for a Just Cause ordinance would grant tenants up to three times median rent in relocation assistance, paid by the landlord, if they’re moved from a unit with six units or less by rent increases of over 25 percent. Landlords of larger buildings would be required to provide renters $10,600, the current amount granted by city policy to tenants forced to move from buildings that have been foreclosed.

The CHJL is also exploring a model used in Seattle that reimburses small landlords for their relocation assistance costs, which may help alleviate concerns that the bill would swamp mom-and-pop landlords unable to cover the additional expenses. Households with an elderly or disabled person, or a child, would also receive an additional $2,500.

While just cause legislation remains pending, advocates and progressive City Council members continue to ask if it will be enough. Amid a pandemic, how can Chicago’s government protect tens of thousands of residents threatened by eviction?

Hurdles to Passage

For a period earlier this year, it appeared that the city was primed to pass Just Cause legislation with the mayor’s blessing. While DOH and CHJL had been in negotiations on the details of the proposed bill since last year, housing advocates were still surprised to hear Mayor Lori Lightfoot express her support for just cause at two high-profile appearances in February. However, as Chicago Reader housing writer Maya Dukmasova noted, something was amiss: Though the mayor repeatedly used the term “just cause” in her speeches, the description of the legislation she was giving only captured a small portion of the larger proposal put forth by activists. Lightfoot described the injustice of long-term renters forced from their homes with just 30 days’ notice but didn’t mention anything about the requirement for an actual “Just Cause for Eviction,” leading Dukmasova to question whether the mayor understood the full scope of just cause or was erroneously offering support that she didn’t really mean.

“She’s going around saying she’s supporting just cause eviction, but the fine print doesn’t seem to be anything like that. [What she’s proposing is] a good thing, but it’s a different thing,” Dukmasova said on the Ben Joravsky Show. “It’s not just cause eviction… so why do you have to slap this label on it that means something different, just to make it sound more progressive than it actually is?”

Just a few weeks after these events, as coronavirus lockdown measures were first put in place, DOH pulled out of negotiations with the CHJL. Then, in May, the mayor’s office introduced a separate bill, informally known as the “Fair Notice” bill, that more closely resembled the mayor’s previous description of what she supported. The Progressive Caucus of the City Council raised concerns that the bill made little difference for renters, and a series of revisions followed. The amended Fair Notice bill, passed into law in late July, bears a stronger resemblance to many of the demands made by housing activists. Renters in buildings with more than six units now possess a right to cure (or repay) any nonpayment of rent until the eviction order has been filed. The notice period for nonrenewal has also been extended in two cases: For households with tenancies of three years or more, landlords must now give four months’ notice, while tenancies between six months and three years will now receive 60 days. Landlords must also provide extended notice should they intend to increase rent prices, with the same notice periods applying. Still, according to Frank Avellone, policy director at LCBH, the core dilemma addressed by Just Cause remains unanswered: If a landlord wants to remove a tenant for someone who can pay higher rent, nothing in the Fair Notice bill prevents them from doing so.

“Just cause certainly runs to the heart of the way we’ve structured society for centuries, and it forces us to ask what is it that we value, and how do we prioritize these things,” Avellone said. “If we say that housing is a human right, security of tenure is one of the most important aspects of those values.”

Although sharing some overlapping characteristics with Fair Notice, the proposed Just Cause legislation, first introduced by members of the city’s Progressive Caucus in City Council in June, would go further to keep renters in their homes. To prevent displacement stemming from dramatic rent increases at the time of renewal, the just-cause bill mandates that tenants can choose to take relocation assistance if rent is increased by 25 percent or more, and forbids increases of 50 percent or higher. Furthermore, unlike the Fair Notice bill, the just-cause ordinance would stop no-fault evictions or nonrenewals, with landlords also forced to pay relocation assistance in both cases. These measures are intended to help tenants land on their feet in case of an unexpected move, and to serve as an enforcement mechanism to prevent landlords from forcing out lease-compliant tenants who wish to remain in a unit.

Despite the support for Just Cause from the many community organizations and other advocacy groups involved in the CHJL, concerns from South and West Side councilmembers, the real estate industry, and community development corporations have contributed to an uphill political battle for the bill’s passage.

For Kevin Jackson, executive director of the Chicago Rehab Network, an umbrella organization representing place-based nonprofit developers and community development corporations, including several organizations that are also participants in the CHJL, there’s concern that Just Cause could have unintended consequences for disinvested communities. While Jackson argues that the city needs dramatically more affordable housing in all communities to serve the rental population, he says he’s heard from member organizations who worry that aspects of Just Cause, specifically the relocation provisions, could hamper outside investment in housing in areas already witnessing mass-scale demolition and housing instability.

“We have concerns about the unintended consequence of potentially limiting investment or causing disinvestment because of that type of ordinance,” Jackson said. “How do we make sure that you don’t have people saying, ‘Well, I’m not going to invest now’ in communities that really need it, or undermine someone’s ability to keep a four-flat going?”

Meanwhile, market-rate landlord associations have decried both Just Cause and Fair Notice for infringing on the property rights of landlords. This backlash, further articulated by numerous South and West Side councilmembers in hearings on both bills this summer, has led to much of the political and philosophical opposition to this legislation, according to Avellone.

“The industry has this ideological sensibility about the sanctity of private property, and that’s why you see them opposing everything across the board, whether it has any financial consequence for them or not,” Avellone said. “They jealously oppose and protect against its infringement.”

For Jackson, representing the interests of mission-driven landlords who provide much-needed low-cost housing in a city that currently has an affordability gap of nearly 120,000 units, his biggest concern right now is the precarious state of many renters and low-income owners alike, both threatened by the economic effects of the pandemic. “We’re in a situation where renters are vulnerable and facing illegal lockouts, but also that owners are equally vulnerable, having to keep up with debt financing and taxes,” Jackson said. “Being a membership of groups who own mission-driven housing, there’s a sense that they want residents to remain, they’re not interested in changing who they serve.”

Although the just-cause ordinance faces a steeper political climb than the Fair Notice bill, CHJL member organizations continue to rally support and petition uncommitted members of City Council, including working on hosting a subject-matter hearing on the bill within the Housing Subcommittee. Meanwhile, the 11 members of the Progressive Caucus sponsoring the will likely prove essential in working out the details of the Just Cause bill with its skeptics, First Ward Alderman Daniel La Spata notes.

“I’m willing to sit down with the community development corporations in my ward to better understand where and why they’re concerned, and how we can make sure that this works for everybody,” La Spata said.

Echoes of 2008

Advocates still hope to put policies in place to protect families at risk, but many have already recognized the parallels to the last eviction and foreclosure crisis, after the 2008 financial crisis. Alderman La Spata was working as a housing organizer with the Logan Square Neighborhood Association at the time, and witnessed many families pushed out of long-time homes in that crisis. Now that he represents much of the same area, one of the city’s most rapidly gentrified community areas over the last decade, he worries that similar patterns of real estate speculation will follow these events and threaten the long-term community fabric.

“There were dozens of properties bought up by real estate interests who were very happy to sit on them and let them become dilapidated until the market turned around,” La Spata said. “Oftentimes, they’d demolish and build a new single-family home that ended up going for a million dollars, or a three-flat where each unit is going for half a million and up. For many actors, there’s no interest in community stability.”

Antonio Gutierrez has witnessed countless developers in ATU’s Albany Park neighborhood evict low-income and undocumented households on short notice to rent to higher-income households. For these tenants, Just Cause would make it harder for landlords to do this after the pandemic, allowing families to stay in their homes as the economy begins to reopen.

“We’re better off having good actors within our communities,” Gutierrez said. “Having bad actors and bad developers that are doing it with only the intention of greed and profit-making, that doesn’t meet the needs of the community around housing.”

Even though advocates push for the government to do more, the state of Illinois ranks as the ninth-most responsive jurisdiction in the Eviction Lab’s ongoing COVID-19 Housing Policy Scorecard of the states and Washington, D.C. In August, Illinois made $300 million in rent and mortgage grants available to households behind on payments, with rental households eligible for $5,000 in assistance and mortgage holders eligible for $15,000. Chicago’s government also made $33 million in rental assistance available to households at or below 60 percent of Area Median Income in this period. Finally, with the COVID-19 Eviction Protection Ordinance, passed in June, landlords are required to engage in good-faith negotiations for seven days with tenants after filing a five-day notice for nonpayment if the tenant has lost work due to the pandemic.

Although Gov. J.B. Pritzker has once more renewed the statewide eviction moratorium, now in place until Dec. 12, renters who have fallen behind on payments remain in a tenuous position, especially with no federal action forthcoming to extend unemployment benefits. In June, an analysis of U.S. Census Bureau survey data by online lending company Lending Tree found that Illinois had the third-highest rate of rent deferrals, behind Ohio and Maryland. A recent NPR survey found that half of Chicago households have reported serious financial problems due to the pandemic, with 63 percent of Latinx and 69 percent of Black families reporting difficulties.

For Avellone, the issue of just cause fits within the context of COVID-19, the racial justice movement, and the ongoing climate crisis as a matter of bedrock principles. Securing a Just Cause ordinance is a necessary first step to ensuring that housing is a human right, he argues. More fundamentally, it’s a question of principles, and whether elected officials are committed to transformative policies that match the scale of the many crises we’re facing today.

“We can’t just keep tinkering around the edges anymore,” Avellone said. “You have to look at things more fundamentally and ask, what is the value system that we’re giving preference to? What is it that we need to be doing in this era that will be with us the rest of our lives? If we don’t start doing things from a different vantage point, there will not be an us in the future.”

Great article! While we are all keeping our fingers crossed that these protections will be extended, it does not address the problem facing the owner-landlords of the small apartment buildings and two- three-, and four-flats so common in many of our neighborhoods. Woodstock Institute research estimates that over 50,000 are at risk of foreclosure. No surprise that many of them are in Black and Brown neighborhoods. Owner-landlords need rent to pay their mortgage; and if they’re lucking enough not to have a mortgage, they need the money for maintenance because 75% of these buildings are over 80 years old.

While extending the moratorium on evictions is critical right now, the owner-occupants of our small multifamily properties need help too. We can’t afford to have these buildings left vacant or sold to Private Equity firms: been there, done that, it sucked. Policymakers need to help tenants so that they can pay their rent, help the owner-landlords of small apartment buildings so that they can pay their mortgage and maintain their properties, or a combination of both. But doing nothing is not acceptable.

Thanks Annie Howard for such a comprehensive story. Chicago is the nation’s largest city without “just cause” eviction protections. This should not continue in a state run by Democrats. Let’s hope the pandemic gets the constituencies that elect Democrats to statewide office to make support for “just cause” a litmus test issue for candidates.

If a lease ends, and the tenant continues to occupy the property, then an eviction has a “just cause.” The landlord and the housing provider had an agreement, called a “lease.” When the parties signed the lease, they agreed on an ending date for that lease, which was known to both to the tenant and the landlord. An eviction enforces that agreement.

A lease is a temporary right to possession. Both the landlord and the tenant (who are ostensibly intelligent adults) know this when they enter into the contract. It is not ownership of the property.

This so-called “just cause” ordinance essentially grants perpetual ownership of the property to the tenant–ownership the tenant did not pay for. In fact, under this subversion of basic property law, the landlord is required to pay the new owner (the tenant) to get her or his property back (by paying over $10k in “rental assistance”).

I agree that there is a severe shortage of affordable housing throughout the country, and particularly in Chicago. This ordinance (and others like it) which prevent access to the courts, destroy the freedom of contract, and dispossess property owners, is no way to achieve it.