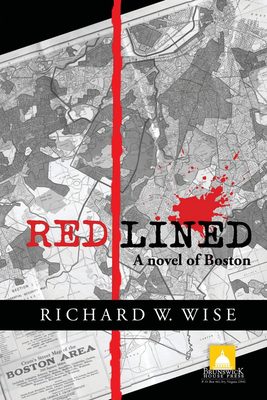

With a deep understanding that’s largely based upon his experience working as a community organizer in Boston’s Jamaica Plain neighborhood, Richard W. Wise tells a powerful story of the urban development wars that took place at a time when powerful developers, financiers, politicians, and nonprofit leaders promoting upscale place-making in pursuit of “trickle-down benefits” were pitted against poor and working-class residents struggling to preserve their neighborhoods. In the first few pages of Redlined: A Novel of Boston, Wise seizes the attention of readers eager to know who caused Sandy Morgan’s death. He then quickly exposes them to an epic battle over the future of American cities being waged in low-income communities throughout the U.S. during the last quarter of the 20th century. This semi-autobiographical novel describes how a small group of community activists, working through their churches, compelled the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to require banks to disclose where they were making loans. The clear pattern of discrimination revealed by the data subsequently helps this network of faith-based organizations negotiate a major reinvestment agreement with local lenders.

The book is set in the early 1970s when state and federal transportation officials proposed the construction of a new highway to ease the commute of South Shore residents traveling into downtown Boston. During the land acquisition phase of the Southwest Expressway Project, which featured the widespread use of eminent domain, an unlikely coalition of neighborhood activists, historic preservationists, urban environmentalists, and mass transit advocates came together to defeat the initiative, placing the future of the neighborhoods located along its right-of-way up for grabs. Wise focuses Redlined on the fierce struggle that took place over Jamaica Plain’s redevelopment. Here, a large number of vacant lots and abandoned buildings remained following the cancellation of the highway project, which discouraged local lenders from providing mortgages in the area, in turn causing real estate values to plummet and many property owners to abandon the community.

In Redlined, powerful real estate interests with extensive financial and political ties quietly assemble land within Jamaica Plain for a mega-project, using campaign donations, charitable gifts, and illegal bribes to secure the support of local officials—and threats of violence and arson to encourage residents to abandon the neighborhood. Early in the story, readers are introduced to a determined group of citizens who mobilize to challenge these efforts. Along the way, Wise exposes readers to municipal officials committed to the machine politics of the James Michael Curley era, religious leaders more interested in their Swiss bank accounts than in saving souls, and Vietnam vets willing to operate outside of the law to defend their neighborhood. While some readers may find Wise’s characters and rapidly changing subplots challenging to follow, few readers familiar with the rough and tumble nature of urban development in Boston and its tribal-like municipal politics will be among them.

Redlined: A Novel of Boston would be a great addition to the summer reading list of anyone interested in Boston’s social history or the struggles of citizen organizations resisting displacement and gentrification—problems that have gotten significantly worse in recent years despite the passage of the Fair Housing, Home Mortgage Disclosure, and Community Reinvestment acts. It is an informative but exciting whodunit thriller that tells a compelling story, with a few creative liberties, of how a small group of Jamaica Plain residents prevented an expressway from destroying their community, pioneered anti-redlining policies that stabilized their neighborhood, and converted the Southwest Expressway’s right-of-way into verdant and heavily-used greenway that transformed Jamaica Plain into one of Boston’ premier, and increasingly exclusive, neighborhoods— something Wise and his organizing colleagues might have found difficult to imagine in 1975.

Many thanks, Professor Reardon, for your thoughtful review of my novel, Redlined, A Novel of Boston.

As Alinsky said, two steps forward, one step back. In the aftermath of the anti-redlining fight, Jamaica Plain slowly gentrified, which eliminated the poor, but made JP one of the most diverse, vibrant communities in Boston.

RWW

Rick Wise serves history of the redlining movement in Boston well with his novel. He well dramatizes the context of that time with his personal knowledge and experience in the redlining battle. Out of the local movement (Jamaica Plain Banking and Mortgage Committee), came an ongoing struggle to address mortgage lending discrimination leading to the creation of the Boston Anti Redlining Coalition and ultimately the Massachusetts Urban Reinvestment Advisory Group (MURAG). MURAG in 1980 stopped the largest thrift in Boston from opening a suburban branch utilizing the state Reinvestment Act that was passed earlier, again, as a result of the nascent work done in Jamaica Plain. MURAG went on to sign a number of precedent setting lending agreements with most of the large banks in Boston at that time. Hugh MacCormack, a Jamaica Plain resident and community advocate led the organization and I serve as its founding Executive Director.

Again, thanks to Rick for a foundational look at how community organizing and activism can change public policy and private investment.

Thanks to Ken Reardon for a fast paced review of what sounds like a grass roots battle for power over a vulnerable community. The folks in Boston led the way early in the fight to save neighborhoods. BTW I tried to buy a copy by following the link – which led me to a “local” bookstore 30 miles away and then even tried to track down the publisher to no avail. I ordered from Amazon. Looking forward to reading it.

Mr. Wise’s plot reminds me of a building I was involved in when I was doing code enforcement work with the New York City Department of Housing Preservation & Development as an attorney during the 1980s. This older multiple dwelling in Borough Park Brooklyn had a predominantly Latino population in an Orthodox Jewish neighborhood. On a quiet night during the litigation several tenants in the building told me that a man came running down the steps yelling “Fire! Get out!” This occurred before anyone smelled smoke or saw the fire. The arsonist ran into a waiting car and sped away.

To my disappointment the existing tenants eventually left the building without arson charges being brought despite a serious investigation by the Brooklyn D.A.’s Office and a co-conspirator to the arson having come forward. I still, to this day, think about this incident and would say to anyone that Wise’s work is not an exercise in science fiction. It proves that even a shop worn building can be valuable enough, depending upon it’s location, for someone to empty the existing tenants out.