Photo courtesy of LTSC

Three years ago, Shelterforce covered the stories of a handful of community development organizations that had begun work under multi-million dollar grants from ArtPlace. The grants gave housing and social service providers an opportunity to explore whether they could further their missions by integrating arts and culture strategies into their work. The initiative—the Community Development Investments (CDI) program—has ended, but the work hasn’t. This is the second in a series of articles that follow up on the three organizations we featured. (If you haven’t read it yet, you can find the first piece here: “How Artists Helped an Organization Adapt to Demographic Change.”)

Many communities of color across the country are grappling with the challenge of preserving and celebrating their cultural heritage in the face of economic difficulties and political backlash against diversity and inclusion. Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo neighborhood, one of three Japantowns in the United States, is one such community.

Prior to World War II, Little Tokyo had a population of 30,000, but the internment of Japanese Americans in the 1940s decimated that number. Almost eight decades later, Little Tokyo is a vibrant community and a living testament to Japanese and Japanese-American culture. But its residents face myriad problems such as an affordable housing shortage, gentrification threats, and a lack of social support for multicultural families.

The Little Tokyo Service Center (LTSC) is a community development organization that, in its own words, operates to “promote community control and self-determination in Little Tokyo” while providing social services to those who are most in need. For three years, it has carved out room in its overall programming to integrate art and culture strategies into its outreach programs and its own internal operations.

Creating Something from Nothing

In 2015, LTSC became one of six organizations to win a $3 million Community Development Investments (CDI) grant from ArtPlace America to explore the use of arts and culture strategies in its community development work. The program ran roughly from 2015 through the beginning of 2019.

When LTSC won the grant, Little Tokyo was already facing gentrification forces, as its location near downtown Los Angeles made it prime real estate for investors. Dean Matsubayashi, the executive director of Little Tokyo Service Center (LTSC) at the time, told Shelterforce in 2017 that in light of the pressures of gentrification, “we can either shape our future or be shaped by the many pressures, policies, and plans that are being imposed upon us right now.” LTSC endeavored to do the former, in part by using art and culture to celebrate the rich heritage of the community and to promote local businesses.

Matsubayashi passed away in September of 2019 but his vision of leveraging art to sustain Little Tokyo’s historic and cultural roots lives on.

“Part of the true power of art is creating something from nothing or imagining something in a place where it hasn’t been before,” says Grant Sunoo, director of planning for LTSC. “That is so powerful, especially in communities of color where we have historically been told ‘This is what your community should look like.’”

Strengthening Community Through Art

At the heart of much of LTSC’s arts and culture work is +LAB (“Plus Lab”). The word “lab” suggests experimentation, and +LAB explores integrating artists and their creativity into not only LTSC’s own community development efforts but those of other community partners. Projects undertaken by +LAB include those that enrich the community by inspiring cultural pride or empower residents to take on advocacy issues. +LAB also has an annual three-month artist residency program in which California artists, including one from the Little Tokyo community, work with local organizations on creative placemaking projects that engage residents.

One +LAB project designed to highlight the cultural significance of place in Little Tokyo involved First Street North, a national historic landmark.

+LAB held a poster contest in which Little Tokyo artists had the option of either creating a design that conveyed the street’s history or a design that projected a vision for its future. Winners of the contest were selected by community stakeholders, including business owners, community organizers, residents, and other artists. One of the winning posters, created by artist David Monkawa, depicted how parts of Little Tokyo had been lost to gentrification and commercialization over the years, including the 1952 razing of a block of residential and commercial buildings to make way for the City of Los Angeles’s new police headquarters. Monkawa’s poster was a reminder of these losses, and encouraged people to fight to preserve Little Tokyo moving forward.

Image courtesy of Little Tokyo Service Center

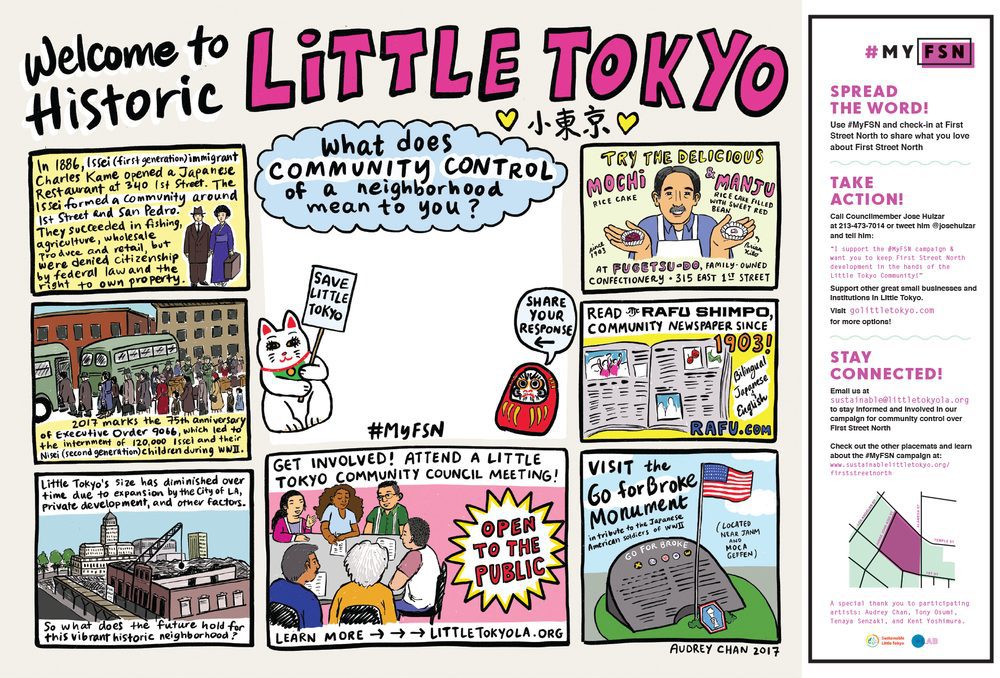

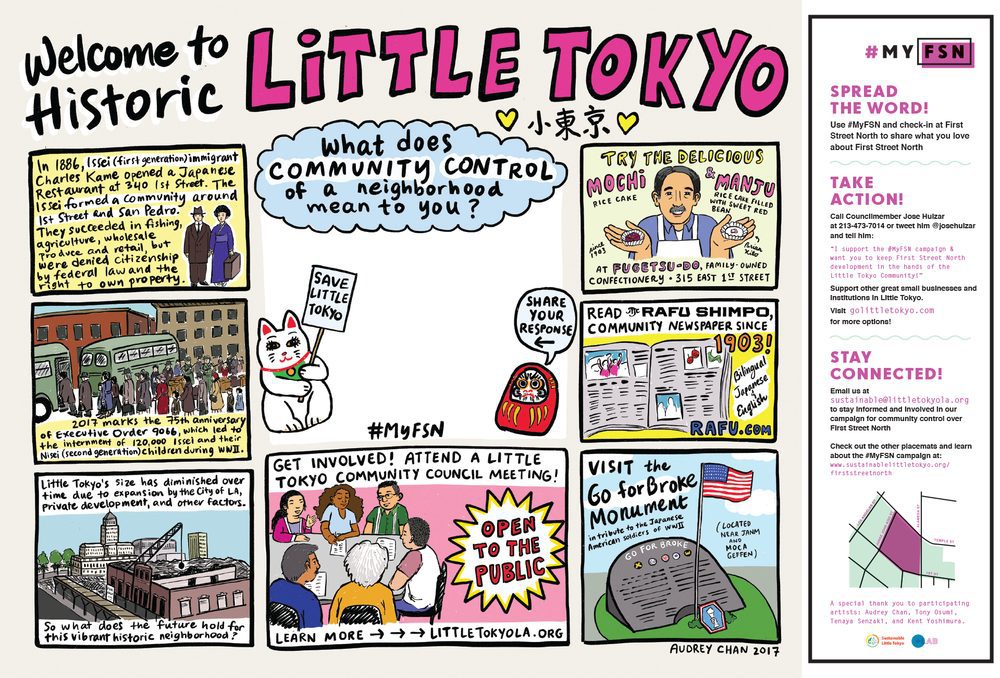

Another project was the creation of placemats and table runners designed by local artists that highlighted the history of First Street North and included tips on how residents could maintain community control. Placed in popular Little Tokyo restaurants, the placemats listed contact information for council members, explained how to attend a community council meeting, and gave social media links so residents could share their thoughts on First Street North.

Alexis Stephens, a senior communications associate for PolicyLink, a racial and economic equity research and advocacy institute that partnered with ArtPlace to document and measure the impact of the grant, was impressed by LTSC’s use of both projects as community calls to action. “Little Tokyo Service Center clearly has such a legacy of activism and culturally relevant and culturally based community-building,” Stephens says. “The way that they were able to use arts and culture as a provocation to promote their work around community control over land and self-determination when it comes to issues around planning in the future of the neighborhood was extremely inspirational.”

Thanks in part to the ArtPlace grant, LTSC merged its long-time expertise in affordable housing and its newfound focus on art with the purchase of a residential building called Hotel Daimaru. While the majority of the building is for low-income tenants, five single-room-occupancy units are designated for +LAB artist residents.

The building also houses a space called 341 FSN—referring to the building’s street address, First Street North—where LTSC and local partners, such as the Japanese American National Museum and Sustainable Little Tokyo, design activities that use art to promote community control.

One such program, titled “Seeds of Our Grandmothers’ Dreams,” explored the lives, hopes, and dreams of Japanese-American women before they were forced into internment camps. Another, “New Directions in Nikkei Music,” explored the Japanese-American community’s connection to its heritage through song.

Articulating A Vision for LTSC

It took LTSC some time to learn how to articulate its vision for the creative placemaking work it was engaging in—in part because staff needed to first become clear about that vision themselves.

“There were times when we’d have conversations with folks and they’d be trying to talk to us about a project and we’d [say], ‘well that’s not exactly what we’re looking for,’” Sunoo of LTSC recalls, adding that artists would then ask, “well what do you need?” to which he’d reply, “I’m not really sure yet.”

Over time, communicating this became easier as LTSC clarified its goals: to ensure that Little Tokyo maintained control over its own destiny by using art to inspire community activism, to increase awareness of the community’s cultural assets, and to underscore Little Tokyo’s significance to the greater Los Angeles region.

In sharing experiences with other CDI grantees like the Southwest Minnesota Housing Partnership, LTSC learned that it was beneficial to bring in artists to help them better communicate with potential partners, says Dominique Miller, the organization’s planning administrator. “We found all of us in the CDI program were experiencing some of the same challenges—one of the main ones being just communicating with artists,” says Miller.

LTSC hired Erica Rawles, a Los Angeles-based artist who specializes in writing, photography, and installations, in February 2019 to work on staff as a creative strategist. With a background in community engagement, art education, and organizing, Rawles knew the languages of both art and community development.

From her unique vantage point, she could see LTSC’s biggest challenge: “An organization like LTSC wants to have certain goals and certain outcomes and see certain results,” says Rawles. “Yet, coming from an artist’s perspective, I know that I go into a project having no idea if it will come to anything and it’s more about an exploratory process.” Learning to bridge those two approaches would be critical to its success.

Rawles encouraged her new colleagues to experiment and use art to engage community residents even if they were unsure of what the outcome might be. They brainstormed a multicultural barbeque event for Casa Heiwa tenants that included arts engagement activities, which not only enabled neighbors to enjoy artistic expression, but also helped LTSC gather resident input for the Downtown Los Angeles Community Plan. “At first I think some of them [staff] reluctantly joined me in this process,” Rawles admits.

Rawles also guided staff through developing a question-and-answer process to use when they put out a call for artists. Questions like “What is it about this project that makes us feel like we want an artist to be a part of it?” and “Why is art valuable in this situation?” If those questions couldn’t be answered, staff would go back to the drawing board to clarify their goals. Rawles believes that by answering those questions before getting artists involved, LTSC was able to maintain strong relationships with the artists they selected. “If you aren’t clear about why you want to work with an artist then the artist might not feel like their work is valued,” says Rawles.

Merging Two Worlds

For LTSC staff, the ArtPlace grant fundamentally changed the way the CDC operated. Before the grant, staff at LTSC typically thought in terms of numbers and concrete plans. The artists it worked with tended to be most comfortable diving right in without concrete plans, and discovering some new truth along the way.

In the first year of the grant, LTSC’s selected artists collaborated with local arts organizations to create artworks and projects promoting community engagement under the broad theme of “Community Control and Self-Determination.” “We got some amazing projects and artworks that really redefined the way we were engaging with folks in the neighborhood,” Sunoo says. Performance artist Dan Kwong spent about three months conducting what he called informal story circles, attended by seniors and younger residents, in which they would describe their personal memories of Little Tokyo.

Kwong took their stories and brought them to life in a live performance titled “Tales of Little Tokyo.” In an interview with Little Tokyo-based Japanese-English language newspaper Rafu Shimpo, Kwong said, “Little Tokyo is a precious and vibrant community with over 130 years of history. Our stories are at the heart of that history, and collectively they become the voice of our community.”

In the grant’s second year, LTSC chose the theme “Ending Cycles of Displacement.” One of the chosen artists, traci kato-kiriyama, designed “Past Present: Conversations with Future,” a performance installation and soundscape crafted using letters written by community members who touched on family separations that have spanned generations in the Little Tokyo neighborhood. What they learned from that exercise is that there is no proven formula to ensure success. “I think we’re still trying to figure out where on the spectrum to end up in terms of the literal translation of our goals and leaving room for experimentation and freedom,” Sunoo says.

An Inward and Outward Shift

Of the lessons LTSC learned, Sunoo believes the longest lasting will be the way LTSC partners with artists and arts and culture organizations within the Little Tokyo community going forward.

One such partner is the Japanese American Cultural and Community Center (JACCC), which describes itself as a hub for Japanese and Japanese-American arts and culture. Ironically, as LTSC has deepened its arts and culture activities, JACCC has received a grant to expand its work in community organizing. “The social service community development agency is now working with artists and the arts and culture agency is working with community organizers and doing community planning, which I think is really beautiful,” Sunoo says.

LTSC plans to continue work in this space. In 2019, it was awarded an Enterprise Rose Fellowship, a program that partners community development organizations with artists, administered by Enterprise Community Partners. With the fellowship, LTSC will create a full-time, two-year staff position for an artist to build on what was accomplished through the CDI grant.

Dominique Miller, the organization’s planning administrator, is looking at ways to expand LTSC’s creative placemaking work, and asks, “What is our role as an ethnic-specific community in the middle of LA surrounded by other communities of color who are also undergoing the same challenges? I think there’s a responsibility [of] skills sharing and knowledge sharing. How can we share with others and support the work that they’re doing? It’s important that all communities are preserved and sustained. If one falls, it leaves everyone else vulnerable as well.”

Sunoo agrees. “We’ve been thinking a lot about creative placekeeping work as an ecosystem within the neighborhood—and thinking about what our role in that ecosystem is.”

Corrections: The original article inaccurately described Rawles’ relationship to two LTSC processes. She did not herself issue calls for artists, and the wrong events were listed as the results of the brainstorming process she led.

Comments