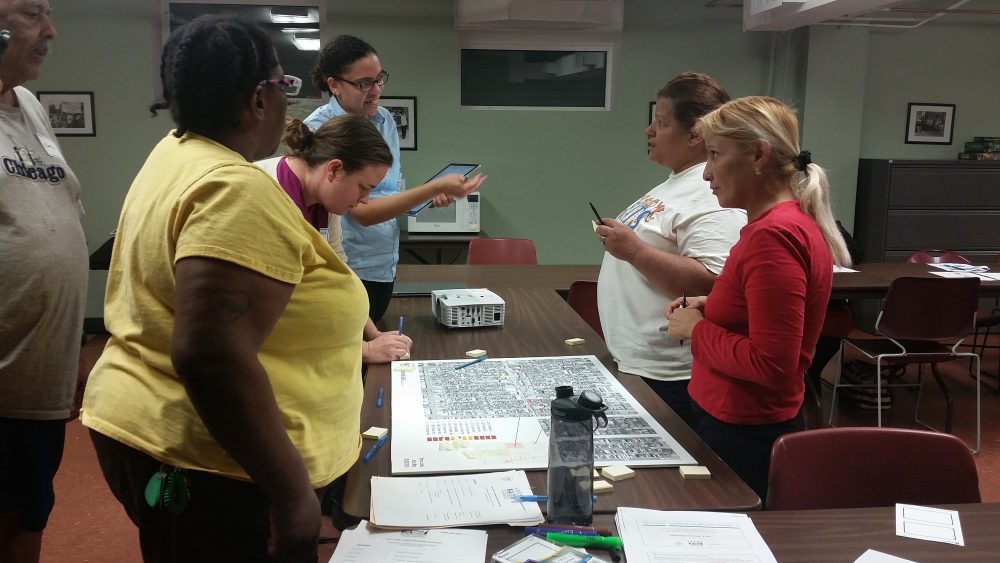

A focus group meeting. Photo courtesy of LUCHA

Affordable housing developers know about housing. They don’t necessarily know about health.

For staff members at LUCHA, a Chicago-based community development corporation, that fact was driven home back in 2012 when the organization was rehabbing of one of its affordable housing developments and several residents asked whether the new units would have carpeting.

“It was an issue since their kids had asthma,” says Charlene Andreas, LUCHA’s director of affordable housing. Andreas noticed that many of the rehabbed units were carpeted—and recalled few of the residents owned vacuum cleaners. That made the homes particularly dangerous for asthmatic children, something LUCHA had never considered. It raised the organization’s awareness about how the built environment can affect health, says Andreas, though staff members weren’t then in a position to act on it.

Years later, LUCHA was in the planning phase for a new, 45-unit development, and was determined to do things differently. So when researchers from Enterprise Community Partners solicited participants for a five-month health and housing pilot program that would launch in mid-2016, LUCHA staff members jumped to apply.

Enterprise Community Partners had been increasingly focusing on the nexus of health and housing in recent years, and the pilot was an effort to formalize some of that thinking.

“We know that the decisions that affordable housing designers and developers make can affect residents’ health,” says Krista Egger, senior director of initiatives at Enterprise and one of the project’s researchers. The pilot’s goal, then, was to encourage housing developers to partner with public health professionals in order to solicit input from the community, identify residents’ most pressing health needs, and design developments that would address those problems.

Working closely with staff from the U.S. Green Building Council and the Health Impact Project (a collaboration of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Pew Charitable Trusts), the researchers came up with a framework to guide the process. The Health Action Plan (HAP), as they’re calling it, outlines community concerns and avenues for addressing them.

“It embeds public health expertise in the design and development process, and ensures there’s a research phase, a community engagement phase, a protocol for measurement, and a follow-up in terms of impacts,” says Egger of the Health Action Plan.

Together with four other CDCs—Grant Housing and Economic Development Corporation in Los Angeles, New Orleans’s Gulf Coast Housing Partnership, Mercy Housing Southeast in Atlanta, and SKA Marin in Great Neck, New York—LUCHA was accepted as part of the pilot. That meant the groups, all of which had housing projects in early pre-development, were expected to identify public health professionals who could be collaborators, and then jointly create a Health Action Plan.

But that first step wound up being a major stumbling block. “Trying to find a public health partner was kind of a difficult process,” says Andreas. Part of it was the number of potential partners: there were simply too many options, from university academics to private firms to nonprofit organizations. And many, it turned out, were too sophisticated for the small-scale project LUCHA had in mind.

‘Trying to find a public health partner was kind of a difficult process.’

In the end, LUCHA settled on the Illinois Public Health Institute (IPHI), a group that had recently worked on a health impact assessment and also had experience engaging with community groups.

LUCHA’s experience was typical of the organizations in the pilot, says Egger. “All of them ended up with a very good partner, but it took several months and was hard.”

Once the CDCs found suitable partners, though, their collaborations moved forward easily. The public health professionals combed through data to understand local health needs, then checked those findings through meetings with the community.

A ‘tree’ exercise that helped facilitate a discussion about the causes and reasons for health issues in the community. Photo courtesy of LUCHA

Being able to rely on someone who understood health statistics and research techniques was key, says Andreas. “Having IPHI definitely made a difference in what we identified,” she says. “We just wouldn’t have been able to pull the amount of data that they did, to really make the decisions and conclusions that they were able to make.”

For example, given their experience, Andreas and other LUCHA employees were primed to focus on air quality and its concomitant issues of asthma and allergies. “But maybe I had blinders on,” muses Andreas. What the IPHI folks also found were very high levels of isolation, depression, and anxiety among community members—something the LUCHA staff hadn’t considered.

That finding turned out to be relevant with just about every other CDC, as well. “We found that one of the health priorities that came up again and again was social isolation—people not feeling like they had connection with their neighbors, or not knowing how to access services,” says Egger. Luckily, that was something that could be addressed through good design on the part of the CDCs and their architects. Common spaces could be drawn to increase the number of spots where residents would cross paths and potentially interact, for example; outdoor walking paths could include open areas with benches.

But the public meetings were just as important as the research, says Stephany De Scisciolo, another Enterprise researcher on the project. “In all cases, [the CDCs] found that the community engagement piece was really important and enlightening,” she says. “Hearing [something] from residents is different from thinking about it.”

For example, in New Orleans, the data indicated that the biggest public health challenge was violent crime. But during the community meetings, residents said they were actually most worried about a canal that ran behind the property; they didn’t want to let their children play outside because they were afraid they would drown. In response, a landscape architect added a bamboo grove that would prevent kids from easily accessing the canal, and the parents are now comfortable letting their children play outside.

“The interesting thing is that nobody ever would have realized it unless they’d gone through this process—and it will have a huge impact on the lives of these kids,” says Egger.

The pilot wrapped up at the end of 2016, but Enterprise is continuing to promote the Health Action Plan. There’s been significant interest from other affordable housing developers, and new funding vehicles created by Enterprise and Kaiser Permanente require that affordable housing developers follow the Health Action Plan process as a condition of accessing the funds. To ease the process—particularly the difficult first step of finding an appropriate public health professional—Enterprise is building a network of potential partners who are interested in working with housing organizations, as well as a standard scope of work that can be used to formalize the collaboration. Those resources will be made available to any housing groups that are interested.

For their part, the LUCHA folks say the process was invaluable. “I don’t feel like we can do affordable housing development without doing Health Action Plans in the future. It hits a lot of the outcomes we want,” says Juan Carlos Linares, LUCHA’s executive director. “But the pilot is true to its word—we’re just kicking it off. We’re trying to establish a culture of doing this.”

Editor’s Note: Krista Egger’s name was misspelled in a previous version of this article.

Comments