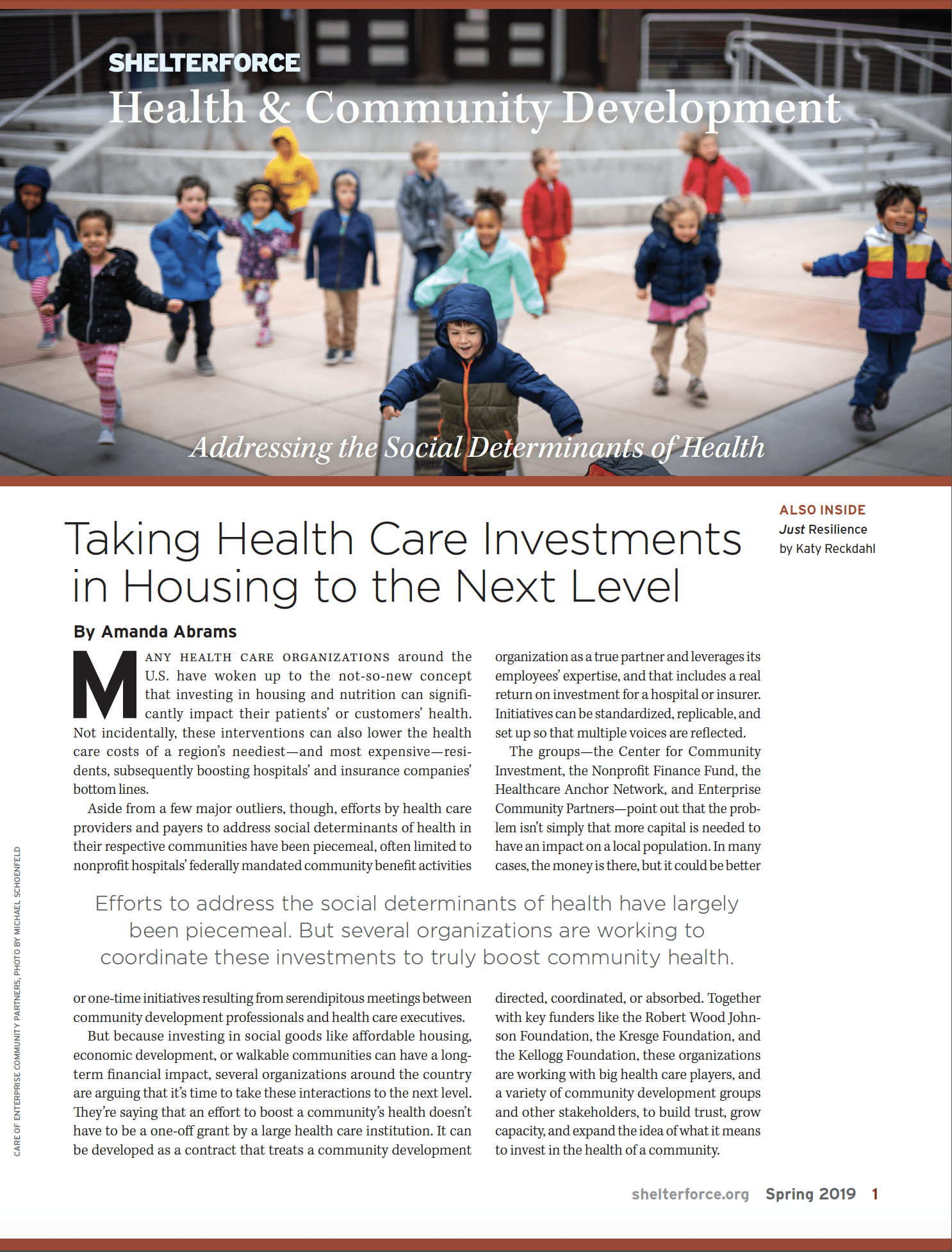

A Habitat for Humanity home in Washington state that was completed using the Habitat-Passive approach. While it cost about $15,000 more to build, the homeowners’ monthly heating costs will be reduced from $150 to less than $20. Photo courtesy of John Moon

Is it worth increasing the cost of construction to provide homeowners with a heating bill that’s less than $20 per month while consuming less energy than a hairdryer? That’s the question the Whatcom County Habitat for Humanity’s board asked in 2013 as it grappled with keeping homeownership viable for low-income families in the county.

The question took the board on a nine-month journey into emerging building science and environmental stewardship as it pursued the best way to create a decent home at a reasonable price that could remain affordable well into the future regardless of energy prices.

In May 2017, Washington state’s Whatcom County Habitat for Humanity finished a 1,200-square-foot, four-bedroom home in the town of Birch Bay that is capable of producing more energy for heating than it consumes. Equally important, the home is affordable to own by a family who couldn’t afford to rent a two-bedroom apartment anywhere in Whatcom County. Since then, Habitat has completed six energy-efficient homes in the county, and it recently broke ground on a project that will add another 72 homes to the tally.

Making It Green and Making Green Pay

It was clear that building green is the way of the future and requires more resources up front, especially cash. What wasn’t clear was how Habitat’s simple, decent, and volunteer-friendly building standards would coexist with the prescribed materials and techniques of common green building standards, such as LEED, Evergreen, or Energy Star. The cost implications were daunting.

On the other hand, the Passive House standard— popular in Germany for over a decade—was very simple. If a home consumed less than 38 kBTU per square foot per year and was air tight, it would qualify as green, and surpass any other standard as well. More importantly, it prescribed nothing and this gave Habitat the green light to design a home that was not only easy to build by volunteers but could use materials and fixtures that were appropriate and inexpensive to maintain. Maintenance costs are a part of long-term affordability, and green technologies that are costly or complicated to keep up are not a good fit for Habitat’s clients.

We are able to get incredibly good results without taking on the most complicated or expensive approaches.

In partnership with Bellingham’s Building Performance Center, Habitat figured out the projected energy consumption versus projected cost of construction for every major system in the house, from the foundation to the roof. If the Habitat Construction Committee changed the type or size of a window, it was able to determine the effect it had on the heating bill and ultimate affordability. Our Habitat-Passive approach combined the highest possible efficiency standards with easy-to-teach construction techniques, resulting in a product that could deliver a significant return on investment.

Using Habitat-Passive techniques increases construction costs by $12.50 per square foot, or about $15,000 total, for the typical Habitat home. At 0 percent (the rate at which Habitat lends) over 30 years, the increase in the monthly mortgage payment is about $42. According to the Building Performance Center, which for two decades has worked to ensure that low-income housing in Washington State is healthy by offering training and weatherization, average monthly heating costs would be reduced from $150 to less than $20, freeing up more than $100 each month that homeowners could use for food, education, health care, or a rainy day fund.

Thermal Bridging and Insulation

The passive house we developed operates on similar principles to a thermos. Everywhere the inside of a home touches the outside of a home there is opportunity for heat to be transferred away from the living area and wasted. Every two-by-four stud in a conventional wall system transfers heat away from a house in the same way an automobile’s radiator transfers heat away from an engine. This is called thermal bridging. The first big challenge to designing energy-saving floor, wall, and roof systems was how to separate and insulate the inside structural components from the outside. With hundreds of studs in a wall system, this was a big problem to solve.

However, Habitat volunteers love to build walls. So we asked, why not build two walls—a load-bearing wall that rests on the foundation wall, and an interior, non-load-bearing wall that rests on the floor system. Except for the window and door penetrations, the thermal bridging challenge had been solved.

Airtight with a Fresh Air Feel

Building a house like a thermos also requires that the building envelope be leakproof. For the Habitat-Passive standard this means 0.6 air exchanges per hour at 50 pascal barometric pressure. The accumulated area of unsealed penetrations in the outer wall could be no larger than the diameter of a quarter.

If you add up all the holes the electricians, plumbers, and other subcontractors make in the outside wall, this was a challenge. The challenge was met by taping the seams of every piece of exterior sheathing, including the ceiling of the uppermost living space, installing high-performance exterior doors and windows, and pressure testing the home. Leaks are discovered by following the smoke from an airflow test pen and then sealed before any of the exterior or interior walls are finished with siding or sheetrock. Pressurizing the home also determines that the air exchange standard is being met.

This level of tightness produces fresh air and moisture challenges, which can be addressed with an inexpensive and easy-to-maintain HRV (Heat Recovery Ventilation) system. The HRV continually controls and exchanges the air within the home, removing moisture and stale odor and replacing with fresh outdoor air. Both air streams go through a filter and heat exchanger where the warmth of the outgoing air heats up the incoming colder air with up to 90 percent efficiency. As the home is so well insulated, light bulbs, appliances, computers, and people help heat the house and only spot heating is needed for the coldest days. Habitat is using radiant cove molding—an electric resistance heat panel placed near where the wall and ceiling meet, and operated by a thermostat—for spot heating as needed, due to its reasonable cost and low maintenance.

Sticking to our dual goal of return on investment and energy-saving results, there are some technologies we don’t use even though they would save some additional power. For instance, in the absence of a grant, we do not use a mini-split heat pump because the energy recovering HVAC system in place is so efficient. Even though the mini-split would result in lower power bills, the additional cost does not make economic sense. We are able to get incredibly good results without taking on the most complicated or expensive approaches.

The Final Touch: Net Zero

The ability to use the utility-owned power grid as a battery makes solar power a viable option in the Northwest. The 25-year warranty provided by the local solar-cell manufacturer means that long-term maintenance and replacement of the system is affordable to the Habitat homebuyer. The energy-conserving construction techniques combined with the ability to generate power at the home site results in a home whose carbon footprint for heating will be zero.

We have found that building high-efficiency homes is an evolving process, but a worthwhile one for our homeowners. We’re still learning, and hope others will join us on this journey.

Comments