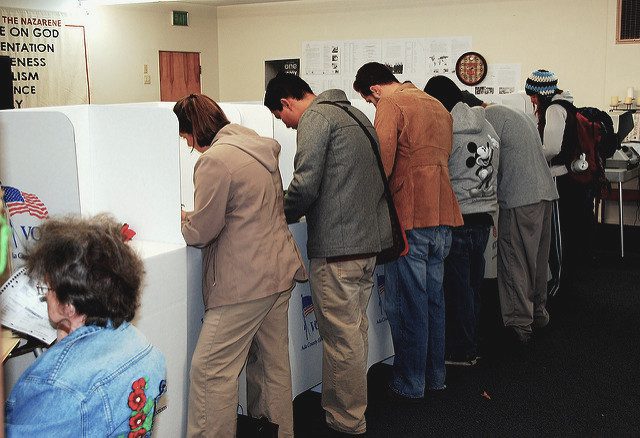

Precinct 86 voting booths. Photo by Whitney via flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Cities are seeing more political support for building housing now than in at least the past four decades. Yet some housing advocates believe public support is lacking, asking “Why haven’t voters been buying the case for housing?”

This was the subject of a popular article in Shelterforce last week by Rick Jacobus, one of the nation’s most insightful housing commentators. He based his conclusion on an October 2018 LA Times survey of 1,300 Californians in which 13 percent of respondents blamed the affordability crisis on “too little home building.” Twice as many blamed “lack of funding for affordable housing” or “lack of rent control” for the problem.

Jacobus’ article sought to explain this alleged disconnect between “experts” recognizing that building housing is necessary to address the affordability crisis and voters who supposedly do not. Jacobus writes, “Isn’t it possible that voters understand something that the experts are overlooking?”

Actually, no. Voters join experts in backing more housing.

When I interviewed housing activists across over a dozen cities for my book, many were frustrated by anti-housing zoning laws and other barriers. But most felt the public supported building more housing. They saw this goal being frustrated by older, whiter homeowners whose perspectives did not reflect their cities as a whole or often even their own neighborhoods.

I am not surprised that when voters have a chance to support pro-housing candidates or ballot measures, they increasingly do so. Recent election results indicate more support for ending zoning obstacles to new construction and building more affordable housing than at any time since Congress passed the American Housing Act of 1949.

Housing Won in November

The November 2018 elections, only weeks after the LA Times poll, refuted concerns that voters are not rallying to build housing.

In Berkeley, often a NIMBY stronghold, the very pro-housing Rashi Kesarwani won a city council seat, replacing a longtime member who often opposed new market-rate units. A student candidate, Rigel Robinson, also replaced a less consistently pro-housing council member. Incumbent Lori Droste, the most pro-housing member of the prior council, easily won re-election in a heavily homeowner district. In Berkeley, politics are becoming more pro-housing.

In a heavily contested East Bay state Assembly race, Buffy Wicks defeated Richmond city council member Jovanka Beckles. Wicks backed a state bill (SB 827) to increase density on transit corridors, which Beckles opposed. Wicks was considered more pro-housing and development and ultimately prevailed.

This past November, California elected someone who is arguably the nation’s most pro-housing governor in Gavin Newsom, well ahead of his time in arguing that building more housing increases affordability. After vowing to build 3.5 million new homes, he would have been political toast if voters had opposed this idea.

Voters support for housing was particularly clear in Austin, Texas, a longtime anti-housing, pro-single family home stronghold. Austin voters faced a clear choice in their November mayoral race. Incumbent Steve Adler backed land-use reforms increasing infill housing; challenger Laura Morrison attacked the mayor for “threatening the character of single-family home neighborhoods.” If voters did not see building new housing as a key to increased affordability, Adler wouldn’t have prevailed by 40 percent.

Austin voters also passed a $250 million affordable housing bond and rejected an initiative to require voter approval of all upzonings for housing.

A council majority now supports Austin building a lot more housing. And after Councilmember Greg Casar recently introduced a proposal to allow six-story buildings citywide that are 50 percent affordable, the measure quickly won strong support.

Austin exposed the myth that voters do not share experts’ views on the need for housing. To the contrary, Austin was an example of how a small minority of homeowners have held cities hostage to land-use policies that the broader electorate does not support. And when voters are given a chance to vote to get housing built, they take it.

Housing candidates did not win everywhere. In the primarily white, homeowner dominated Silicon Valley city of Cupertino, an avowedly anti-housing majority took control of the city council. But trying to get support for new apartments in such upscale neighborhoods has always been difficult.

California’s Pro-Housing Mayors

If California voters don’t believe building more housing promotes affordability they would elect mayors who share this view. But so far they haven’t. Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti touts housing construction as a strategy for affordability; critics like the AIDS Healthcare Foundation criticize him for being too pro-development. Garcetti faced no major opposition in winning a second term.

The state’s second largest city, San Diego, also has a mayor who believes building more housing increases affordability. Mayor Kevin Faulconer, first elected in 2014, tweeted on Jan. 15: “We must change from a city that shouts, ‘Not in my backyard’ to one that proclaims: ‘Yes in my backyard!’ From a city of NIMBYs to a city of #YIMBYs! Together, we’re going to transform San Diego into a #YIMBY city!”

Faulconer’s term ends in 2020 and candidates for mayor are already actively recruiting the support of YIMBY Democrats of San Diego.

Sam Liccardo is the pro-housing mayor of San Jose, the state’s third biggest city. He recently endorsed SB 50, the state bill to increase housing along or near transit corridors.

Stockton Mayor Michael Tubbs endorsed SB 50 as well. It would be hard to reconcile his election with Stockton voters allegedly opposing his stance that building housing increases affordability.

Oakland’s Libby Schaaf strongly supports building housing to increase affordability. She easily won re-election last November.

In San Francisco’s 2018 special election for mayor, two candidates openly opposed a state bill that increased housing on or near transit corridors. One candidate backed the bill, a position many believed would hurt her in supposedly anti-development San Francisco. That candidate, London Breed, is now the city’s mayor.

So if you believe that voters haven’t been buying the case for building, you need to explain why voters in California and elsewhere keep electing candidates making this case.

Only Election Polls Matter

In March 2015, a San Francisco poll found that 65 percent of voters would support a ballot measure to halt new project approvals in the Mission District for one year. Only 26 percent of voters said they were opposed. Those numbers are consistent with the findings of the LA Times poll, and also support Jacobus’s conclusion that voters aren’t buying the case that building more housing improves affordability.

So what happened in the November 2015 election? The Mission moratorium on new housing lost, 57 to 43 percent.

Election results are the best and only meaningful indicia of voter sentiment. As for pre-election polls, no one should expect homeowners to admit that their own opposition to housing drives unaffordability. Survey respondents have an incentive to blame “greedy developers” rather than themselves for restricting housing supply, and for not acknowledging the steep rise in their own property values earned by excluding renters and apartments from their neighborhoods.

Jacobus’s article offers important ideas on expanding support for building housing. He also points out that more of the benefits of new construction need to reach the low-income, working, and middle-class people getting priced out.

But when it comes to whether voters support building more housing as one key strategy for expanding affordability, election outcomes show the case is closed—they do.

A version of this post originally appeared on beyondchron.org.

It’s way past time, but not too late, to create, fund and implement a national policy addressing housing and housing affordability that is adoptable, and adaptable, to local, state and regional needs. If you want to improve health, education and economic equity outcomes, then start with the foundation to success, housing.

The affordability of anything is related 2 its scarcity. Since all politicians, urban planners & the commercial real estate industry facilitate & subsidize their economic growrh/built environment agenda in the race 2 become a metroplex, they bear responsibility 4 the upward price pressures on low-moderate income people.

We need 2 replace this “success” model 2 a socioeconomic framework, but I don’t see the political will r community/neighborhood engagement 2 focus on this situation.

Programs, initiatives, nor “innovations” will do much 2 address these irreversible challenges. Support a steady-state approach & not a manufactured one.