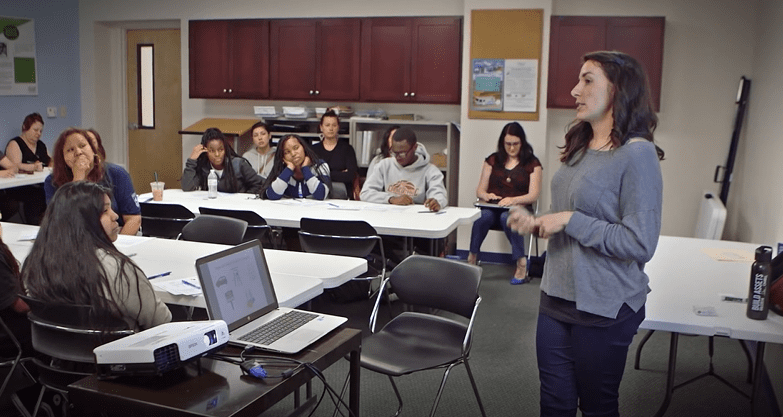

A representative of the nonprofit Innovative Changes leads a credit building class at Stephens Creek Crossing, a Hope 6 property owned and operated by Home Forward. Photo courtesy of the Credit Builders Alliance

David Moreland, a resident of Stephens Creek Crossing in Oregon, speaks with Home Forward’s resident and community service coordinator about building his credit by reporting rental payments to the three major credit bureaus. Photo courtesy of the Credit Builders Alliance

A good credit history is crucial in today’s economy. Without a prime credit score—commonly defined at or around 660—individuals pay higher interest and fees on financial products like credit cards and loans, if they qualify for those products at all. They also spend more on essential services like car insurance and cell phones. This can create sustained expenses inequality—paying more for credit and everyday needs than necessary on a regular basis. For example, individuals with subprime credit scores spend nearly $3,000 more in interest to purchase a $10,000 used car than a person who has prime credit. This is particularly problematic for people of color and those living in lower-income neighborhoods. According to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, they are significantly more likely than their white and higher-income counterparts to have no credit history at all, or to have one that either has too little information or information that is deemed to be reliable enough to generate a credit score.

Because having no credit history or a poor credit history inflates costs, makes it more difficult to save, and impedes wealth creation, some nonprofits, funders, and even entire cities, like Boston, have embraced credit building as a powerful strategy to help underserved households take control of their financial lives, and, over time, build wealth.

Although credit building is not always an obvious solution for people experiencing immediate financial stress, having no or subprime credit is a driver of financial hardship. The impact of credit stress on individuals and their families not only affects their personal situations, it influences economic conditions in their communities. For example, neighborhoods with large numbers of households with no or poor credit are often the target of fringe financial-service providers like payday lenders and check cashers. These companies often cluster in and around communities inhabited by households of color and/or those with lower incomes, many of which become the target of aggressive, even predatory, credit marketing and practices. Conversely, neighborhoods with higher credit scores per capita are generally more financially stable, with households contributing to and serving as a source of strength for their communities. Not only do these neighborhoods boost the local economy by spending more, they do so by increasing the rates of homeownership, generating greater property tax income, small-business growth, and more employment opportunities for residents.

What is Credit Building?

In order to sustainably build credit an individual must have—and successfully manage—open financial products over time. By definition, credit building requires the existence of at least one positive trade line on an individual’s traditional credit report. For homeowners, these can include monthly mortgage payments, which is almost always reported to the credit bureaus. For renters, however, a positive rent history is often invisible. As a result, renters’ credit histories typically present an incomplete and negatively skewed assessment of their risk.

And this matters. Approximately 36 percent of U.S. households live in rental housing. That percentage is even higher for families of color and those living at the lower end of the income spectrum: Black and Hispanic households are twice as likely as white households to rent their homes, and renters account for nearly 60 percent of all U.S. households with income under $25,000 per year. Lacking opportunities to establish or build credit, renters of color and those with lower incomes are shut out of economic progress.

Fortunately, since 2017, all three major consumer credit bureaus have offered a way to include on-time rent payments as valid trade lines on traditional consumer credit reports, so renters can finally benefit from making their monthly payments. This could be particularly beneficial for those with lower incomes; they could build credit without taking on additional debt or incurring the burden of an additional monthly expense simply to have the payment appear on a credit report.

Rent reporting has become a proven way to help these renters build credit histories. For example, from 2012 to 2015, Credit Builders Alliance (CBA) implemented its Power of Rent Reporting pilot, funded by the Citi Foundation. This pilot catalyzed rent reporting for credit building for eight affordable and public housing providers in Texas, New Hampshire, Maryland, Illinois, Ohio, Massachusetts, California, and Oregon. Of the 987 low-income renters whose rents were reported through the pilot, 79 percent saw their VantageScore increase by an average of 23 points, and 15 percent moved into a lower credit score risk tier. Every renter for whom too little information had been available to even create a credit score became scorable during the program. (It is important to note that while VantageScore and newer FICO models, like FICO Score 9, are optimized to integrate rental payments into their algorithms, many creditors—especially mortgage lenders—still use older-generation FICO models that do not take rental payments into account. As a result, even if the rental trade line is reported to a credit bureau, those payments will not benefit a renter’s credit score).

While millions of rental payments are being reported to at least one of the major credit bureaus, most of the reporting is managed by landlords of market-rate, multi-family housing. Why? It’s not just renters who benefit. Rent reporting can help landlords by adding an incentive for on-time payment and offering a competitive advantage in attracting renters with good credit. However, there is much room to expand, especially across the public and affordable housing space.

Despite this promising new credit-building strategy, a major challenge for affordable and public housing providers has been scaling rent reporting. The reasons are multifaceted: federal privacy and HUD regulations, lack of staff time, technology challenges, concerns about compliance with the Fair Credit Reporting Act, and the different data-furnishing policies and procedures imposed by each credit bureau all add complexity to implementing a rent-reporting initiative.

In response to this challenge, CBA has recently partnered with Esusu Financial Inc., a socially responsible financial technology company, to build out CBA-Esusu Rent Reporter, a streamlined and holistic platform that combines programmatic and technical assistance with data transfer support to property managers by providing:

- Assistance in generating simpler, more consistent data files for submission to the major credit bureaus;

- Guidance in navigating federal privacy and HUD data-sharing regulations that require renter opt-in for federally subsidized properties and voucher holders;

- Rental data transmission compliance guidance, data quality control checks, and dispute management assistance; and

- Programmatic expertise and training on credit building, resident outreach, implementation, and best practices for outcome tracking.

While interest in rent reporting among renters and mission-driven housing providers has increased dramatically over the last five years, some consumer advocates express legitimate concerns about unintended consequences that could harm renters’ credit profiles. For example, many states permit tenants to withhold rent payments when there is a problem with the condition of their rental units. If a payment is late beyond 30 days, it could negatively impact a renter’s credit score (though at least one credit bureau, Experian, only reports positive payments). As with all things in the credit space, there is no silver bullet. However, those who consistently do not pay their rent will likely see their credit score harmed if a collection account shows up on their credit reports. By reporting their residents’ rental payments, responsible affordable and public housing providers offer those residents who do pay their rent on time the opportunity to build their credit histories.

CBA’s pilot and subsequent work with a dozen such housing providers has shown that overall, the effect on credit scores is positive. In addition, CBA’s experience reveals that renters who are offered rent reporting are more likely to engage in other financial capability or asset-building programs—like financial coaching, Individual Development Accounts, and homeownership preparation—successfully improving their credit profiles and other financial wellbeing outcomes.

Housing programs can do more to expand this evidence-based mechanism for helping their residents build credit. Offering rent reporting is one way that affordable housing programs can further help their residents improve their financial security. They should all be at least considering the possibility.

Comments