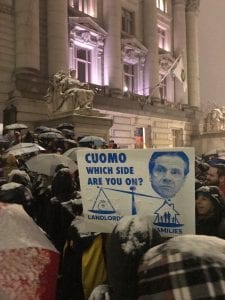

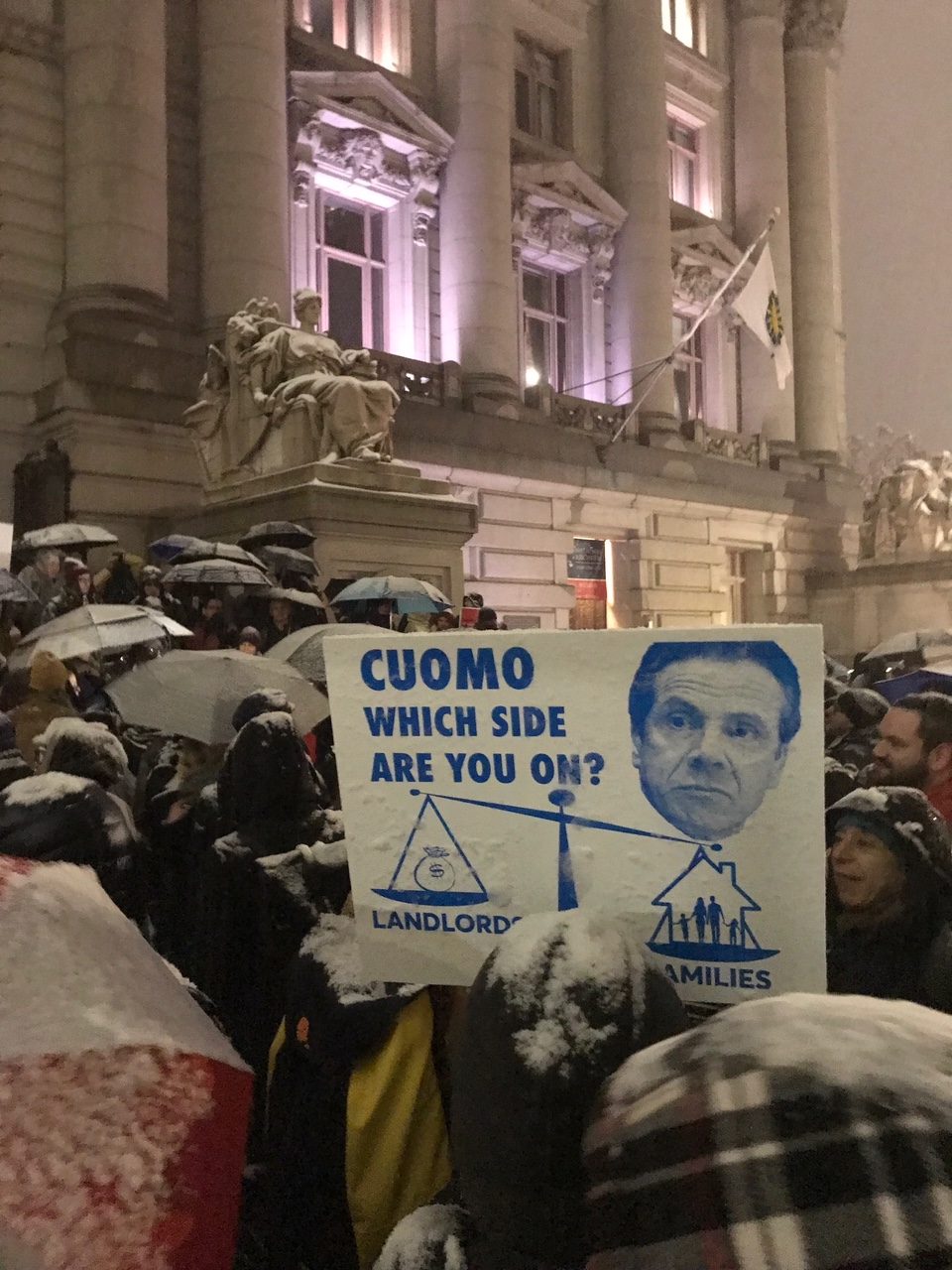

Housing Justice for All rally on Nov. 15, 2018. Photo courtesy of Pete Harrison

Voters in New York have spoken and they want relief from the affordable housing crisis. Last week they handed control of state government to Democrats, most of whom ran on progressive, pro-tenant platforms. Particularly in the state senate, which flipped for the first time in years, many first-time candidates beat pro-developer incumbents by rejecting real estate money and instead embracing the call for universal rent control.

This doesn’t mean voters will get relief, however. With current rent regulation laws set to expire early next year, voters have set up an unprecedented fight between progressive housing groups and real estate interests. It will be a brutal fight. For proof of this, housing advocates in New York need only to look at California.

National real estate groups spent $80 million successfully defeating a rent control ballot initiative known as Prop 10. These groups, as well as powerful local groups like the Real Estate Board of New York and Rent Stabilization Association, won’t blink at spending lots of money to fight universal rent control in New York. (One of the biggest is Blackstone, which owns Stuyvesant Town in the East Village where I live.)

California and New York have extremely different political contexts, so making direct comparisons has limited value. However, there are several important lessons that New York housing advocates can take away from Prop 10’s defeat.

No. 1: Define Universal Rent Control Clearly

Prop 10 didn’t stand a chance as a ballot initiative, partly because of the money aligned against it, but equally because it was confusing. It was not a yes/no vote on rent control. The language of the proposal was about repealing the state’s Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act that prevented local cities or towns from enacting any kind of new residential rent control.

That left a lot undefined for voters. They were asked to vote on repealing something—and many did not have a specific sense of what repealing it would mean for their city or town, or for them personally as renters or homeowners. Even with millions of dollars from tenant groups and the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, this dynamic made it easy for well-funded real estate interests to fill in the gaps and define it how they wanted to. This clearly cost Prop 10 a lot of should-be voters.

That is less of an issue with universal rent control in New York. Although the scope of the proposal is still being worked out, the broad goals, and who benefits, is clear: every rental unit in New York state will become protected (it’s less than half now.) Every loophole that allows landlords to raise rents, evict tenants, or deregulate units will be removed. Every renter will have new eviction and harassment protection.

Though universal rent control is easier to understand than Prop 10, it is important that activists and progressive legislators work together quickly to define the specific proposals around it before real estate interests start flooding the air with advertisements against universal rent control. This will make it easier to rally the broad spectrum of renters that stand to benefit from the plan, particularly market-rate tenants who must be brought on board to pressure other legislators in the Democratic Party.

No. 2: Seize the New Political Landscape in Albany

Pressure is key. California, just like New York, is blue, but that hasn’t translated into progressive housing legislation. This pattern cost them with Prop 10, which first died in a Democrat-controlled committee before reappearing as a ballot initiative. There are not enough Democrats in office in California with the stomach to challenge the real estate industry and its wealthy homeowner constituents to enact the type of far-reaching reforms necessary to fight the housing crisis.

That had been the case in New York before the November election, but now Democrats control all three branches of elected government and have a rare window to challenge the status quo. Democrats have dominated the Assembly for years, but the big difference is the Senate, where Democrats took control for just the third time in more than 50 years, fueled by an aggressively pro-tenant wave of first-time candidates.

Housing Justice for All rally on Nov. 15, 2018. Photo courtesy of Pete Harrison

The wildcard will be New York’s Governor Andrew Cuomo, who ran to the left because he was pushed there by a spirited challenger. He has been a big friend of the real estate lobby for as long as he’s been in politics. He is now in uncharted territory, but it appears that he can no longer hide behind New York’s longstanding closed-door deal dynamic.

Unlike in California, having complete control of state government should mean that universal rent control would get considerable attention from legislators. The severity of the crisis along with the significant shift away from real estate money in elections should keep pressure on the governor and other members of the Democratic Party who might otherwise be wary of angering the real estate industry.

Defining the proposals for universal rent control quickly and keeping activist groups engaged throughout the process will hopefully be enough to turn the electoral momentum into firm legislative action.

No. 3: Debunk Classic Economic Arguments Against Rent Control

In California, the real estate lobby spent the majority of its money on television ads harping on the classic Econ 101 arguments against rent control. These arguments are not as strong as they appear. The reality of the housing market has always been more complicated than simplistic models suggest and it is critical to push back on them.

First, studies that claim rent control harms the creation of new housing or the quality of existing housing fail to properly account for the more demonstrable variables that limit supply in tight and densely populated markets like New York, San Francisco, or Los Angeles like natural geographic barriers, social preferences of land use, the limited extent of transportation networks, and even a desire to limit competition among developers.

Second, they tend to underplay how decades of federal and local government policies have privileged real estate and empowered financial markets to commodify housing. The housing market‘s priority is enriching investors instead of meeting the overwhelming demand for affordable shelter. That explains how the Low Income Housing Coalition estimates that the U.S. is missing 7.2 million affordable housing units, yet 250,000 units sit empty in New York City alone.

Third, they ignore the bigger problem with the housing market: rent-seeking behavior. There’s only so much land, particularly in desirable markets like New York where its value has skyrocketed over the last 20 years as more people and firms want to move here (for better or worse). This has made city landowners incredibly wealthy.

The pay-to-play nature of our political process means that they also have a disproportionate amount of power over things that impact the housing market, like property taxes, zoning, and affordable housing policy. This almost always harms the public while driving up property values. It helps explain everything from why so many commercial spaces are empty to why it costs so much to build new affordable housing and homeless shelters.

When we acknowledge that the housing market in reality encourages rent-seeking behavior and show how much it corrupts public policy, rent control becomes a legitimate and necessary intervention to empower tenants and the broader public against economic and political exploitation.

Prop 10 was ultimately a bad presentation of a compelling and urgent public policy choice. Even if real estate interests hadn’t spent so much money distorting it, it failed to capture the general public’s attention or imagination.

That doesn’t have to be the case in New York, where universal rent control has already done that for many renters and voters. Now that it has a shot in Albany, California’s experience can help it get over the finish line.

Comments