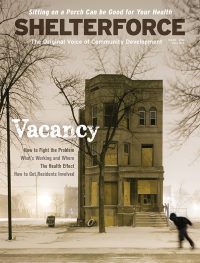

Homes in Buffalo, New York. Photo courtesy of the Center for Community Progress

The Olde Allegheny Garden in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Photo courtesy of the Center for Community Progress

While many former industrial cities and rural communities have struggled with systemic vacancy and abandonment for decades, the 2008 housing crisis wrecked neighborhoods in virtually every corner of the nation. As local and state officials in urban, suburban, and rural areas sought new tools and strategies to stem and reverse the negative impacts of vacant, abandoned, and deteriorated properties, land banks emerged as a top priority. Eleven states passed land bank legislation between 2009 and 2016, and according to ongoing research by the Center of Community Progress, there are over 170 land banks currently operating in the United States.

Land banks are generally defined as public entities, usually public nonprofit corporations or governmental entities, that are designed to play a lead role in returning vacant, abandoned, and tax-delinquent properties to productive uses that are consistent with community priorities. Land banks vary dramatically, reflecting the tool’s flexibility in meeting a community’s unique needs. Land banks are creating pipelines of properties to support quality affordable housing and equitable development, helping communities address former industrial sites (brownfields), assisting with recovery efforts from natural disasters, and engaging residents in innovative vacant land reuse strategies. Though we are 10 years removed from the housing crisis, the need for land banks only seems to grow, as systemic poverty and inequality continue to undermine the stability of neighborhoods in virtually every city and region.

How are land banks being funded, given the inherent challenges of working in some of the most disinvested neighborhoods, where weak market conditions often fail to attract responsible investment? Various funding strategies that have been tried over the last 10 years provide some lessons about what’s successful and suggest some trends to expect going forward.

Lesson No. 1 — Land banks work best with a predictable, recurring funding source.

Stabilizing and revitalizing disinvested neighborhoods is not an overnight endeavor. Land banks require planning, patience, and partnerships—and dedicated, recurring funding affords land banks the opportunity to carry out meaningful community engagement, pursue long-term strategies, and pilot innovative partnerships.

Ohio is the only state that has meaningfully solved the land bank funding challenge. Its Delinquent Tax Assessment Collection (DTAC) is the standard of excellence in the field. Included in Ohio’s 2009 land bank enabling legislation, this provision allows a county (land banks can only be created at the county level in Ohio) to annually direct up to 5 percent of delinquent property taxes, interest, and penalties collected to the county’s land bank for dedicated, discretionary use. According to the Western Reserve Land Conservancy, about two-thirds of all land banks in Ohio receive the full 5 percent of DTAC funds. To put this in perspective, the Cuyahoga County Land Bank (which covers Cleveland) receives approximately $7 million annually in DTAC funding, and the Lucas County Land Bank (which covers Toledo) receives about $1.4 million. Both land banks are leaders in the national field, illustrating that when practitioners don’t have to focus on chasing the next grant dollar to sustain operations, they can focus instead on innovating partnerships and programs and sustaining progress toward long-term community goals.

The Tri-COG Land Bank, a multi-jurisdictional entity serving the region of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, which is dotted with small, struggling former steel towns, pulled off a nearly impossible task; it emulated Ohio’s DTAC strategy at the local level. Absent state legislation, the Tri-COG leaders understood a multiyear educational campaign with local leaders was the only way to secure buy-in for both the land bank and funding commitments. After three years of genuine and inclusive engagement, Tri-COG launched in 2017 with more than 25 taxing jurisdictions (municipalities, school districts, and the county) voluntarily contributing 5 percent of the total amount of delinquent taxes collected (principal only) from the prior year to provide the land bank with dedicated, recurring funding. The impressive commitments from across the region also attracted a substantial, multi-year commitment from a local foundation.

Lesson No. 2 — A self-financing land bank is largely a myth. Local governments must invest in their land banks.

Early funding strategies in the land bank movement included tax recapture provisions and sales proceeds, both designed to fund land banks through their own activities. However, these strategies have proven insufficient to tackle the scale of the problem and reverse decades of disinvestment.

The tax recapture provision, which has been a common feature of state legislation authorizing the creation of land banks over the last 10 years, grants a land bank a portion of the property taxes on any property it sells for a set number of years. For example, a 5/50 tax recapture means that for the five years following the sale of a property, the land bank is able to receive 50 percent of the property taxes generated by that parcel.

The provision is meant to value and recognize the services provided by a land bank in converting a liability to an asset, but most land bank leaders acknowledge that tax recapture proceeds fall far short of needs. For example, from 2010 to 2013, the Genesee County Land Bank Authority in Michigan had an average operating budget of $9 million, and projected only $50,000 annually in 5/50 tax recapture proceeds. Moreover, many land banks work in neighborhoods with weak housing markets, diminishing the amount that can be realized through property taxes.

Sales proceeds were also initially seen as a promising mechanism to fund land banks, particularly for those land banks that acquired all or most tax foreclosed properties across a city or county. These land banks relied on a strategy commonly referred to as “cross-collateralization.” That is, the few tax-foreclosed properties acquired by a land bank in more stable neighborhoods with stronger housing markets were sold at the highest price possible to generate proceeds to fund rehabilitation or demolition of the many low-value tax-foreclosed properties acquired in disinvested neighborhoods.

The proceeds from property sales have generally been a stable source of revenue for land banks but are still insufficient to meet a land bank’s needs, or are at best unpredictable year-over-year. Moreover, more land bank leaders are recognizing that a focus on maximizing sales proceeds can make it difficult for a land bank to contribute meaningfully to equitable development. Land bank properties offered in more stable neighborhoods with stronger housing markets remain available to only those prospective buyers with access to capital. And properties in the weakest neighborhoods often require multiple layers of public subsidy, which usually come with affordability requirements that further concentrate affordable housing in areas of high poverty. A few land bank practitioners are starting to give value to decisions and outcomes that advance justice and equity instead of those that simply maximize revenue. For example, in 2017 the Albany County Land Bank in New York announced the Inclusive Neighborhoods Program, which offers the local community land trust first rights to purchase, at a discounted rate, homes the land bank acquires in more stable neighborhoods, a real commitment to seeding permanently affordable housing throughout the city.

Tax recapture and cross-collateralization have proven insufficient to tackle the scale of the problem and reverse decades of disinvestment, and their limitations are exactly why it’s so important for local governments to make annual and steady investments in their land banks—just as they do with public safety, human services, parks departments, and critical infrastructure projects such as roads and bridges. There are volumes of research showing how problem properties impose significant economic, social, and fiscal harm to communities. Additionally, many of these problem properties are either underwater, making the economics of investment or ownership impractical, or inaccessible to the market due to financial or legal barriers. A land bank provides a critical public service: cost-effectively intervening in this cycle of decline, eliminating the barriers to responsible investment, and thoughtfully stewarding these liabilities to assets that will improve neighborhood safety, no longer drain local tax dollars, strengthen the tax base, and boost housing values.

There are plenty of examples of visionary local and county leaders who recognize this and champion and secure annual allocations of local tax dollars to sustain the critical work of land banks. In Macon-Bibb County in Georgia, for example, the county Urban Development Authority (UDA) approved a $14 million “blight bond” to augment the work of the Macon-Bibb County Land Bank Authority. With strong county support, the UDA issued the bonds in May 2015 and allocated $1 million to each of the 10 commission districts for “blight remediation,” with the land bank managing the initiative. Officials are already exploring a second round of bonds, given the program’s success to date.

While local annual investments are key, the reality is that many local and county governments are operating within fiscally constrained environments, and cash allocations to land banks may be impractical. As an alternative, many local governments have identified ways to provide in-kind support. For example, in New York, both Broome County and Chautauqua County have approved legislation that discounts landfill-tipping fees for land bank demolitions. Some rural counties that operate land banks, including Marquette County, Michigan, and Cattaraugus County, New York, provide staffing support and services such as legal, payroll, and GIS.

Lesson No. 3 — Partnerships not only are critical to advancing a land bank’s mission, but also provide critical gap funding to boost capacity and outcomes.

A land bank without partnerships is like a car without wheels: it doesn’t work. Given that a land bank’s inventory is primarily vacant land and vacant structures, a vast network of diverse partners is needed to transform these parcels to community assets. Land banks have been creative in tapping traditional and nontraditional partners: affordable housing developers, small mom and pop landlords, urban farming and gardening advocates, foundations, sewer departments, real estate agents, school districts, human service agencies, neighborhood associations, historic preservation groups, anchor institutions, unions and vocational schools, and more.

All of these partners typically bring additional resources to the work, but one is notable in the context of funding. Local foundations have helped land banks get off the ground, leverage other resources, pilot new programs, build out community engagement efforts, and cover annual operating costs. In Michigan, the Kent County Land Bank took this partnership one step further, receiving a $600,000 program-related investment (PRI)—in essence, a low-interest loan from a foundation’s endowment—from a local foundation to help acquire, rehabilitate, and sell about 180 tax-foreclosed properties in Grand Rapids. While this is an excellent way to provide up-front capital for the triage of problem properties, it only makes sense if the housing market is strong enough to generate at least a nominal return on investment, since the loan must be repaid. To the best of our knowledge, this is the only land bank that has used a PRI.

Lesson No. 4 — Land banks must be nimble, entrepreneurial, and seize one-time or limited funding opportunities.

Land banks have grown more sophisticated in tapping all sorts of grant funding from local, state, and federal agencies to supplement innovative programming and advance community goals. However, the 2008 foreclosure crisis presented land banks some unique opportunities to tap significant temporary funding in support of neighborhood stabilization and recovery.

The Hardest Hit Fund, a U.S. Treasury program, was launched in 2010 and authorized the investment of $7.6 billion in 18 states and the District of Columbia to support housing stabilization. In 2013, the treasury department added demolition as an eligible activity, earmarking $622 million for a Blight Elimination Program (BEP). State housing agencies have been managing the BEP in support of the most aggressive demolition campaigns seen in this country in decades. For example, Ohio spent $109 million on demolitions and subsequent greening and maintenance; through March 2018, recipients had completed 7,919 demolitions. The Lucas County Land Bank accounts for 1,297 of those demolitions. Its goal is to hit 3,000 by the close of 2020, most in the City of Toledo.

The string of legal settlements with lending and financial institutions following the crisis also generated a windfall for many states. By 2013, attorneys general from at least eight states had used settlement proceeds to support grant programs for local municipalities and land banks to acquire and demolish or rehabilitate vacant and abandoned properties. In Michigan, Ohio, New York, and Illinois, hundreds of millions of settlement dollars went to land banks. Because of its jurisdiction over Wall Street, only the New York attorney general continues to execute settlements. Earlier this year, for example, the New York attorney general secured another $500 million in settlements with two European financial institutions, resulting in a July 2018 announcement of approximately $40 million to be competitively awarded to the state’s 25 land banks.

Time to Invest

Neighborhoods struggling from decades-long disinvestment, or the more recent housing crisis, reflect underlying economics that prevent or stall recovery. Many disinvested neighborhoods today also reflect a harmful legacy of racist and unjust policies. Whatever the cause, or combination of causes, there is no question that the costs imposed by vacant, abandoned, and deteriorated properties on communities and residents are real and significant. And according to recent research, the signs remain very troubling: vacancy remains at some of its highest levels since 2005; the recovery has been tragically imbalanced across racial groups; and the wealth gap continues to widen. This work is far from over.

Fortunately, from Michigan to Georgia, land banks have proven over the last 10 years to be a powerful and important new tool in stabilizing and revitalizing neighborhoods. And one lesson from the field has become quite clear to us as we work with a wide range of them: the success of a land bank is almost directly proportional to the level of funding it receives.

The good news is that more and more practitioners and public officials recognize and value the public services provided by a land bank, and are funding them accordingly. At the leading edge of the maturing national movement, land banks no longer sit on the fringe of community development. Instead, they are trusted entities, accountable to the public, and funded with tax dollars to patiently implement a community’s long-term vision of safe, healthy, and inclusive neighborhoods for all.

This trailblazing work is not to be understated. It represents a paradigm shift in how governments and community partners approach vacancy and abandonment. And as this new approach continues to pay dividends in ways the status quo never could, expect more and more communities to embrace this role for land banks, with corresponding funding commitments in the years to come.

I am a retired private sector entrepreneur + the Founder and Chairman of the Land Bank (LB) in our county (Westmoreland, PA). Our Redevelopment Authority funded our LB with a $50K loan (since repaid), then we entered into contracts with muni’s and school districts in which they contributed $5K each to participate. 5 years post founding, we’ve acquired over 100 properties and repurposed 70. The properties range from single family homes and vacant lots to hospitals. We’ve been in positive cash since Day 1. An essential element, from my point of view, is having the right mix of core competencies — starting with the Board and then the Sr. Staff. Our Board has 300 years of business experience, incl. CPAs, JDs, etc. No politicians. YOU CAN SELF FUND and sustain it. We have ~10 times the success as #2 in PA.