A training session with community developers that covered state and federal regulations, the social determinants of health and their relationship to the ongoing CDC mission and work, the regulatory framework in Massachusetts, hospital finances and decision-making structures, and how to build relationships with neighboring hospitals. Photo courtesy of the Massachusetts Association of Community Development Corporations

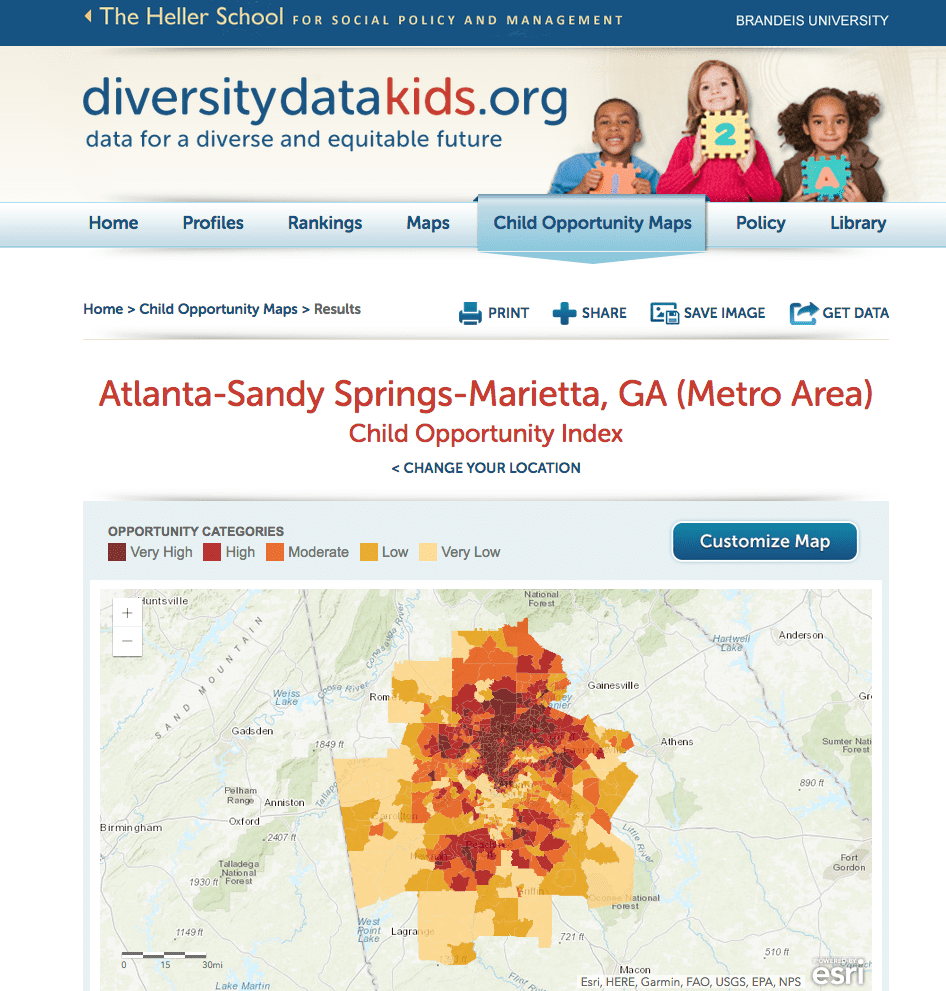

In 2018 there’s no longer much debate about the effects of social and racial inequities on a community’s health. Experts show that a child’s life expectancy can be predicted more by his ZIP code than his genetic code. The social determinants of health, which include housing stability, employment, education, and safety, can have a greater impact on health status than access to or quality of care. As organizations whose mission is to address economic and social inequality and the resulting inequities within a given community, how should CDCs think about their role in effectively addressing the social determinants of health and the barriers to health care? Why should CDCs pay attention to area hospitals that have been asked to address these concerns as part of their community benefit obligations?

CDCs now have significant opportunities to engage with hospitals as they enter this sphere. Since 1969, nonprofit hospitals have been granted federal tax-exempt status in exchange for providing benefits to their communities. Hospitals are required to provide a community benefit in order to maintain that tax exemption. Spending on community benefit has varied, and generally, there has been limited federal or state oversight of this responsibility. Hospital community benefit dollars, traditionally, were spent to provide “charity care” and expanded clinical services, rather than invested in community programs designed to address the underlying social determinants of health.

With the passage of the Affordable Care Act, there has been a renewed focus on community benefits and the role hospitals can play within a given community. Despite President Trump’s continued assault on the Affordable Care Act, Section 9007 of the Affordable Care Act remains, and requires that every nonprofit hospital complete a tri-annual Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) and engage communities on identifying and addressing local health issues. ACA-related IRS rules require hospitals to engage low-income, minority, and medically underserved community members—including those who experience health disparities in the CHNA process— in the community benefit process and specifically the community health assessment. Hospitals are also encouraged to partner with community organizations, faith-based organizations, and other advocacy organizations to address the underlying social determinants of health.

Under these 2014 IRS rules, hospitals are expected to pay more attention to “upstream” investments that prevent health problems and to address “barriers to care,” and they get more credit for doing so. The Affordable Care Act also created financial incentives for hospitals and health care organizations to move toward improving neighborhood conditions to promote better health. For example, the ACA starts to move the system away from fee for service, where hospitals are paid for each service performed, to payment structures based on the success of the care provided (for example, hospitals may not be paid for a patient’s readmission for the same problem if it occurs too soon after discharge).

Some hospitals have embraced the concept of being an “anchor institution.” The idea is that given the size and stability of these institutions, they have a responsibility to move beyond their four walls to address the underlying social determinants of health in their community. A hospital that is operating as an anchor works with community organizations to invest in community improvement and develop strategies to bring about long-term economic improvement opportunities. Detroit’s Henry Ford Hospital, the Cleveland Clinic, Dignity Health, the Mayo Clinic, and Baltimore’s Bon Secours are just a few examples nationally of hospitals and hospital networks that have supported construction of housing, procurement from local minority-owned businesses, job training, and overall neighborhood revitalization and public safety. In other cases, hospitals develop partnerships to support direct construction of housing. Last year, six hospitals in Portland, Oregon, formed a partnership and donated $21.5 million toward building affordable housing. This donation enabled the leveraging of other funds, totaling $69 million.

But too often, hospital efforts, their community benefit plans, and their resource-dedication decisions are accomplished with hospitals calling the shots and community organizations following their lead, rather than the development of more equitable partnerships. Many community organizations are grateful for any hospital support since they have little understanding of what hospitals are required to and able to do.

In 2017, several Massachusetts CDCs had some form of a working relationship with a hospital or obtained funding from one. Efforts included grants to community organizations, and services developed in coordination with the CDC. While this represents some progress, the dollar amounts expended to address social determinants of health still represent only a small amount of a typical hospital’s community benefit funds and virtually none of their extensive assets are invested or deployed in that way. A 2016 study Dr. Paul Hattis and I conducted revealed that 70 percent of all Massachusetts hospitals spent less than 1 percent of their total patient budget on direct community-health investments.

Community organizations must educate and organize themselves so they can become far more proactive in these partnerships, and they must approach hospitals strategically, with an organized base of support, not merely as downstream consumers.

So how does a community development organization with limited resources begin this work? Here are some starting points based on our work in Massachusetts.

Create institutional knowledge: Few community organizations have a good understanding of community health needs assessments (CHNA) or what mandated hospital “community benefits” requirements can and do encompass. These are requirements contained in the Affordable Care Act and 2014 IRS regulations. In 34 states there are additional requirements tied to the granting of a “certificate of need,” which a hospital must procure if it is seeking to expand, purchase major equipment, or change its governance structure.

There also isn’t much understanding or awareness of hospital capital projects and the extent of the accumulation of wealth in hospital assets. All nonprofit hospitals file an IRS Form 990, which includes information on community benefit programs and a great deal of financial information. Seek out local health care experts who understand hospital finance and who can point you to the right government websites and other sources of information. Many states also require their own reporting by hospitals, which include hospital financial information. (Editor’s note: You can also find a lot of the 990 information directly at communitybenefits.org.)

CDCs should read hospital CHNAs and examine how hospitals currently spend money and where funds should be dedicated. CDCs should analyze how extensive a hospital’s community partnerships are, and whether they address the needs of all underserved sectors of the community. CDCs should carefully examine whether hospital community benefit spending is actually aligned with the needs of the community, and whether it is dedicated to address the social determinants of health. Access to the CHNA is a great starting point. Many hospitals post their CHNA on their website, or a simple internet search will generally turn it up. In several states, it may also be available through the attorney general’s office. CDCs should know what the reporting mechanisms are for hospitals within their state and insist on greater transparency and accountability in reporting.

Train staff members: Building the public-health fluency of community developers is essential. For example, I recently partnered with the Massachusetts Blue Cross Foundation and the Massachusetts Association of Community Development Corporations (MACDC) to provide a daylong training to more than 50 community developers. We covered state and federal regulations, the social determinants of health and their relationship to the ongoing CDC mission and work, the regulatory framework in Massachusetts, hospital finances and decision-making structures, and how to build relationships with neighboring hospitals. Part of the training included follow up technical assistance to individual CDCs. As a result of the training, some of the CDCs are strategizing how to link their work with other public health concerns in the community.

Photo courtesy of the Massachusetts Association of Community Development Corporations

Build relationships with hospital leadership: If CDCs want to advance this work they need to build ongoing relationships with not only the community benefit staff from a hospital, but with hospital leaders. Hospital financial officers and investment committees are conventional investors who are not used to investing in community development and will need to be assured that they should be investing more upstream and understand what their return on investment will be. CDCs bring financing knowledge to hospitals, and can help leverage other resources. They also bring a set of developed relationships with community leaders that are based on mutual respect, rather than the “power over” relationship that hospitals often have with communities. CDCs can play a critical role of building an improved relationship of the hospital to the community. A starting point may be learning who is on the community benefit committee and reaching out to them. Another point of entry may be asking to do a presentation to the hospital on the ongoing work of the local CDC and bringing key community leaders to be part of it.

Join with others to affect the regulatory framework: Join and build coalition efforts to improve and expand the regulatory framework in your state. In Massachusetts, for example, there was public support for revising the community benefit guidelines, which had not been updated since 2008. In 2017, Attorney General Maura Healy named a task force to redraft the guidelines to align with federal changes and state department of public health changes. Several community voices, including the director of the Massachusetts Association of CDCs, were on the task force. Throughout the process community activists provided input and feedback. The principles that community-oriented leaders campaigned for included:

- Identification of and alignment with the social determinants of health in the state regulatory framework;

- Expanded and simplified reporting to enable community organizations to effectively understand and compare what hospitals do and their extent of investment in the social determinants of health;

- Transparency on all levels;

- Strategic investment and an end to duplication of efforts;

- Expanded community engagement at all levels of the process, to move beyond initial input to greater partnership;

- Regional cooperation among hospitals

The new guidelines have not been promulgated yet, but a number of these principles have been met. Changing the regulatory framework and enhancing reporting provides a set of tools for CDCs to more effectively engage hospitals.

Analyze the impact of loss of property tax to your community: At a time of increasing attention on the role of nonprofits, and the ongoing discussions on tax reform, CDCs and others need to find out whether their communities are getting their money’s worth on tax exemption, Some communities, notably Boston, have a voluntary payment in lieu of taxes (PILOT) program in which major tax-exempt nonprofits pay 25 percent of their assessed property taxes to the city for providing essential services such as police protection and snow removal. The PILOT payment helps to offset the burden placed on Boston taxpayers to fund city services for all property owners. While it is a voluntary program, most institutions pay a PILOT. Understanding the larger issues of tax exemption and community accountability provides a political and organizing framework for looking at what the hospital currently spends in this area, deciding whether a community is getting its fair share of hospital commitment, and advocating for what the hospital could do to invest in the betterment of the area.

Build communitywide consensus for change: CDCs bring expertise and organizational infrastructure to the table but even with the best information and relationships, they do not have the power and influence on their own to stimulate hospitals to commit even greater resources to this work. Increased hospital investment is prompted by a vision of hospital responsibility and accountability to its host community. CDCs need to be part of a larger community-based movement that unites public health, housing, and other issue-based organizations to campaign for upstream investments. It is not just about financial investment, but about a larger fight against economic and social inequality.

CDCs should look to new partners and organizational forms to move a common agenda. In Massachusetts, for example, the MACDC joined with the Alliance for Community Health Integration, a coalition of health care, social service, housing, and other community-based organizations that work to achieve health equity across race and income.

While this is a welcome development, many of these organizations are more traditional advocacy organizations. In every city there is a broad range of community-based organizations. Seek out organizations that build power through grassroots activism. Some of these organizations have fought hard battles against community displacement, and for raising the minimum wage. Link with strong community organizations that have won legally binding agreements with developers that require specific investments in the community, also known as community benefit agreements (not to be confused with hospital community benefit requirements). In some places, community organizations have negotiated binding agreements on investments in housing, and other community improvements. Organizations like the Fight for 15, a movement of low-wage workers, labor unions, and immigrant rights groups are on the forefront of the fight for social, economic and racial justice. Health equity should certainly be of interest to them. In the Trump era, when there is little support from the federal government, state and local coalitions are increasingly important. CDCs should be strategizing where their interests coalesce with those of other ongoing struggles within their communities.

These are some starting points for CDCs to succeed in a changing world. They need to transform their relationship with hospitals in much the same way they did with banks after the passage of the Community Reinvestment Act. Community-based organizations campaigned hard to ensure that banks provided credit to all neighborhoods and no longer redlined the inner cities. Today, when many communities are faced with major income inequality, community development corporations seek to create a more level playing field. CDCs can no longer look to the federal government for help and support so they must look at the major corporate entities within their communities and bring them into the discussion. Working with area hospitals to address the social determinants of health is a starting place.

Great article. Here in St. Louis we are working with the state’s largest hospital to partner homeless services with emergency room medicine. Hospitals realize that reducing unnecessary emergency room visits saves them money and provides much better healthcare outcomes

RWJF has supported the development of the CommunityBenefitInsight.org web tool that allows community organizations and others to enter the name of a hospital (or region) and see the information from the schedule H – where community benefit expenditures are located – in a user friendly way. Currently with five years of annual schedule H data. On average, of what is reported for community benefit total expenditures, the percent for community health improvement and community building is approximately 7-8%. The site also has a supplemental information tab – where you can view what the hospital reported about who was engaged in their CHNA, and also what they are spending on under the categories of community health improvement and community building.