‘I Love Gentrification,’ by Daniel Lobo via flickr, CC BY 2.0

Several weeks ago, social media ignited in outrage over a sign posted outside a small café in Denver. On one side, the sign read, “Happily Gentrifying the Neighborhood Since 2014”. On the other side, it read: “Nothing says gentrification like being able to order a cortado.” The backlash from community advocates was swift.

The owners of this cafe probably did not intend to create the firestorm they started—they just wanted to sell more lattés—but their gentrification joke-misfire raises a larger, more troubling point: The economic plight of low-income Americans is worsening, and we do not have the public support we need to scale policies that would improve their well-being nor to improve the racially/ethnically segregated neighborhoods in which they live, without displacing them.

Generally, many Americans feel personally empathetic toward those who are struggling, yet our public policies reek of a growing antipathy toward the poor that is difficult to dislodge.

Many of the same people, who in our polls say that they are in favor of better housing solutions for residents, fail to support affordable housing developments when they are proposed in nearby neighborhoods; fail to support legislation that would make it possible to build, create, or preserve existing affordable housing; and fail to support the organizations trying to help low-income people in their communities.

Millions of people are being displaced from their homes because their incomes are not keeping pace with rising housing costs, yet there seems to be very little sustained appetite to address or correct this issue. When we try to raise awareness and offer potential solutions, we often find ourselves largely in conversation with ourselves.

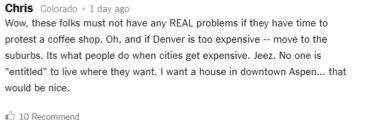

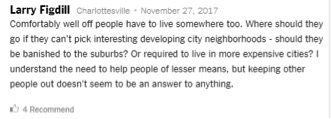

The Denver café reminds us, quite painfully, that despite decades of raising the issue of displacement in the face of rising rents, many people still do not see this as a call-to-action or a failure of public policy. A cursory glance at the comments section of the New York Times article that covered the Denver story shows how ambivalent most people are about this issue.

In a report that I co-authored with a colleague last fall titled, You Don’t Have to Live Here, we examined why housing messaging is backfiring and made some concrete recommendations based on empirical evidence about how to change course. In the report, we argue that we are advocating hard for better policies and programs, but seem to be missing the opportunity to change the public discourse about why housing matters, what “affordable housing” means, why housing is a shared public concern, and what needs to be done to fix this problem.

What We’re Up Against: What’s Backfiring on the Issue of Gentrification

Boiled down, the public narrative on gentrification simply says people don’t have a “right” to live in any particular place, nor do they have standing in a neighborhood simply because they (in this case, African Americans) have always lived there. You only get to live in a place because your efforts (getting an education and job) afford you the right to be there. And if you get priced out, so the logic goes, it is your responsibility to move to a place more consistent with your budget and work ethic. Surely, there are plenty of places left in the United States where housing is still relatively cheap, if people are willing to do the work to look.

This logic reflects the three, very powerful narratives that dominate the public discourse on the place-based work we do and is often responsible for the backfire we get when we try to build public support. And when these narratives operate together (as they often do on the issue of gentrification), it is a trifecta that leads to a predictable refrain—“if you can’t afford where you live . . .” :

- . . . it is your own responsibility to solve that problem because decent housing is an outcome and a reward for making good choices in your life (The Narrative of Individual Responsibility);

- . . . move to a place that better reflects your budget and paycheck (The Narrative of Mobility) and;

- . . . any differences between groups in terms of access to affordable housing reflects differences in the work ethic and cultural values of those negatively affected groups rather than a structural, spatial, and system problem (The Narrative of Racial Difference)

As a result, navigating the public conversation so that it congeals around affordable housing solutions is challenging. As I’ve written before, the public perception of affordable housing often equates it to “public housing” which remains very negative and highly racialized in the public’s imagination. And the concept of “affordability” is still understood by most Americans as much more about how effective we are with our personal finances and budgeting versus issues that reflect broader public concerns.

Surviving the Backfire

Our first inclination in the face of triggering events like the Denver café incident is often to launch awareness or public education campaigns—to which we dutifully bring all the data that we can amass to help us articulate just how bad things really are.

But awareness is not the challenge we face. Most people know how bad the economic circumstances are for low-income families (hell, many of us in the middle class are in the same circumstances). And those who somehow missed this memo are unlikely to see the light just because we have detailed the challenges that low-income families endure when they are displaced.

Instead, this kind of “awareness raising” consistently backfires because it evokes a zero-sum, “what about me?”, separate-fates response. The response often reflects attitudes that do not recognize the struggles of low-income families as unique but as a challenge that we are all trying to stare down. Why focus more attention on the poor when all of us are feeling trapped by an increasingly fragmented social safety net, economic pressures to keep our families afloat, and a government that feels like it is in full-fledged free fall?

Quite frankly, if awareness were the issue, it would be much easier to dislodge, but as many of us already know—and what Christiano and Neimand argue in their March 2017 Stanford Social Innovation Review article, Stop Building Awareness Already, “Not only do campaigns fall short and waste resources when they focus solely on raising awareness, but sometimes they can actually end up doing more harm than good.” From a framing perspective, the harm is that you’ll end up raising the issues in a way that ultimately backfires and ends up reducing public support for the policies you were advocating.

So what helps?

Moving the Needle Requires a Strong Public Will-Building Strategy

To advance support for policies and programs that need scale, we must do a much better job of navigating the three dominant narratives (individual responsibility, mobility, and racial difference) that complicate our ability to communicate why our solutions matter. Here, I highlight some specific considerations to complement the broader range of recommendations in the report.

Gentrification Backfire No. 1: Stories about the displacement challenges that low-income residents face often backfire in the face of the individual responsibility narrative. Our task is to make the story big enough to help others see the issue as a shared structural, spatial, and systems issue that impacts every aspect of our communities and thus, requires a public response.

There is nothing wrong with providing a vehicle for the people most directly affected to tell their stories and to be heard, in fact, this is the hallmark of true community development. Be mindful, however, that it is very difficult to tell stories of displacement that do not backfire because, while people may be sympathetic to the circumstances of displaced residents, as one respondent to our research said, “It still doesn’t change your responsibility to get yourself out of that situation.” In other words, understand that personal stories of displacement rarely trump the very powerful narrative of individual responsibility.

To do this, we need to be strategic. First, be careful to anchor your response in the optimism of your solutions rather than the deep challenges many families face. The latter may have been what brought many of us to this work but it does not work well to engage people who are not already empathetic in this way.

Instead anchor your response in your solutions, which is important if you are to get people engaged over the long term. Building support for systems change, and not against the café (or the idea of “gentrification,” which has multiple and apparently competing meanings for people). Reinforce how providing a home for residents at all levels of the income spectrum is a structural, spatial, and systems issue that is deeply connected to everything meaningful in our cities. Talk about the “pathways to opportunity,” or the systems that need to be strengthened if low and moderate-income families are to thrive alongside their wealthier neighbors in our communities.

Most people forget the ways in which they were helped by our public safety net and the supportive systems around them, so reconnect the dots between their successes and those pathways. Anchoring your message there also gives you the added benefit of making it more difficult for people to default back to the “bootstraps” narrative. If the issue is cast as a structural one (for example, fundamentally about the transit system, accessibility of jobs, technology infrastructure, etc.), it becomes harder to argue that these are problems that can be solved by people simply “working harder.”

Two other caveats are important here. First, be sure to connect housing and the plight of low-income families with other positive attributes and outcomes for the region, from improved education and health to better employment and public safety. Connecting housing and the plight of low-income families to these other attributes helps us to align the value proposition for solving these issues with other community stakeholders.

Second, resist the urge to use the protests as a wholesale attack on business, wealth creation, or economic growth. If acquiring individual wealth is seen as being in opposition to creating opportunities for long-time residents, you will lose this narrative battle every time. Prosperity is a powerful motivation, value, and aspiration for most Americans, so avoid the inclination to play into a frame that pits low-income residents against the ability of small businesses to create wealth and thrive.

Gentrification Backfire No. 2: When we frame our communications in terms of “choice,” “housing markets,” and “moving to opportunity,” we inadvertently trip the wire that invokes moving as a powerful corrective for what ails our communities. Our task is not to remind people that gentrification forces people to move or to argue that poor people have few choices in our housing markets, but rather, to remind them of what they lose when others are forced to move.

The task here is to help people see how they are implicated in, and affected by, displacement in ways that they may not have even realized or acknowledged. Tell them why displacement should matter to them and why they have a stake in it.

More specifically, tell them what they lose if we do not act to build growth in a way that considers the impacts on low- and moderate-income families. What they lose when we continue to engage in policies that exacerbate racial segregation and hoard opportunity away from people.

- when so many of our educators, child care workers and first responders live far away from where they work that it compromises their ability to deliver on the jobs they have been hired for.

- when their grown children can’t afford to live in the once solidly working-class neighborhoods that have now become too pricey for “starter” families.

- the talent that we are “leaving on the table” and the terrible consequences for our economy when only children from high-income neighborhoods get the benefit of an education that prepares them to be innovators while thousands of lower-income children cannot see their way to even finish high school.

- and most important, tell them about the solutions that we have crafted to turn those losses into gains for everyone.

In other words, make it clear that this as a shared public concern and they have a stake in solving it.

Gentrification Backfire No. 3: Our attempts to raise the issue of racial equity backfire very quickly in the face of the powerful narrative of racial difference. Our task is not to shy away from the conversation about race but rather to be strategic in how we raise the issue so that it does not dissolve into cynicism, but rather gets the attention that it deserves in our work.

So often when race, class, or cultural issues are the headline of our communications, responses dissolve into cynicism and derision rather than corrective action. These same issues often undergird the tension over gentrification. The only caveat here is to raise them strategically.

The task is to introduce racial equity into the conversation in a way that gives people a reason (in addition to social justice) to resolve it. That is, we must help people to see their stake in solving some very difficult and emotionally charged dynamics that have plagued our cities and our nation for centuries—not an easy sell.

Tell them how the future will be won by the regions and communities with diverse talent, resources, restaurants, cultural activities, languages spoken, and more. This is in part because our economy, increasingly responding to the pressures of a globalized marketplace, is changing in ways that put a high value on diverse environments. By extension, those communities that remain highly segregated along race and class lines will miss out on opportunities to remain competitive, threatening the livelihoods of all who live in those communities. Help people to see that racial equity is the smart thing to do to ensure that our cities prosper, in addition to it just being the “right” thing to do.

A Public Will-Building Strategy Is Not a Panacea, But You Won’t Get Very Far Without a Good One

As housing pressures continue to rise in many cities across the country, we are likely to see more of these clashes between residents who feel threatened and “newcomers.” Such incidents are bellwethers of the underlying tensions that are created when economic growth is pursued without a concomitant strategy around equity and inclusion.

Surely these issues will not be solved simply by changing our language. Our work to bring capital, community-led solutions, and policy change are key to changing the dynamics on the ground. But without a strategy to build public will, we will not have the support we need to scale the programs we know will help.

Scale requires us to get more public support. Our ability to help guide our communities to a pathway forward, requires us to navigate successfully around the three narratives and the public perception of affordable housing that today operates against us.

This is great stuff. I think you can go farther. Those three assumptions about gentrification aren’t in the public discourse by accident. Gentrification is a direct result of capitalism, and those three assumptions are deeply rooted in basic capitalist assumptions about how the world “should” work. (At least under capitalism!) You point out it’s people of color–especially African Americans–impacted by gentrification in their neighborhoods. It’s capitalism that decimated African nations, tore apart families, enslaved black bodies, segregated neighborhoods, fuels racism. For what? “Protecting” property values and selling more things to have to the greatest number of “haves.”

I’m not grinding a political axe for a specific alternative viewpoint. But this is systemic. Capitalism deliberately undervalues community. Gentrification hits hardest in places where local government refuses to recognize that. IMO, as a former urban planner, to really begin to change the discourse on gentrification we need to change the discourse on community, itself. Once people in a place care about each other again, gaining buy-in for policies that recognize emotional ownership and stewardship of place and improve quality-of-life for all community residents gets easier. Isn’t that the kind of public will we really want and need? That we value and take responsibility for each other again? To me, that’s the planning question. How do we make that happen?

Totally agree Michael. The roots of these narratives are much deeper and eventually, if we want to get to a better place as a nation, we’ll have to address an economic system that has not been made to nurture and develop human talent and potential!

Thanks for the comments!

“public narrative on gentrification simply says people don’t have a “right” to live in any particular place, nor do they have standing in a neighborhood simply because they (in this case, African Americans) have always lived there”

The issue I and many other have with anti-gentrification rhetoric is the idea of a static city where the current economic and ethnic makeup of a neighborhood reflects something that always existed. Many struggling neighborhoods were at one time middle class neighborhoods or had a mix of incomes. Areas became poor when the white middle class left. A loss of businesses and affluent customers further harmed the remaining residents. Thus, most gentrifying neighborhoods are cheaper areas which have had a significant loss in population and businesses. They are not stable places were the residents have always lived and will continue to live forever.

A focus on displacement is a great strategy. In neighborhoods which have lost population you can show that there is space for both new residents and the existing residents. But what I feel like happens is that any investment, new residents, or new businesses are seen as bad. It’s as if we naturally think coffee shops and educated professionals only belong in the suburbs.

My focus would be on the following:

—Helping exiting residents gain jobs when new business open.

—Helping existing residents open businesses in “gentrifying neighborhoods”

—Bridging the divide between new and old residents (showing how both are vital to the neighborhood).

—Ensure jobs pay fair wages (we have more of an income problem than a housing problem).

—Ensure the metro area has good transit that allows all residents to access employment and services

—Affordable housing protections (smaller non luxury units available), so that all workers can live in proximity to their jobs.

—Economically integrating neighborhoods so that no area is 100% poor or 100% wealthy. This means both working for affordable housing near suburban low wage jobs as well as attracting middle and higher income residents into cities.

I really like this analysis–this is the sort of thinking we need to move forward in these discussions, which have gotten very repetitious.

One point I would add to Dr. Manuel’s Backfire #3: I think that a focus on history could be helpful. Make the point that at one point, racially discriminatory treatment was a matter of law and not just custom–and it wasn’t really all that long ago. Not long ago I read that Ruby Bridges, who was the first black person to attend previously white-only New Orleans public schools as a small child, is only 63 years old now–she’s still around! Point being, this history is anything but ancient, and therefore it is absolutely still affecting people’s life trajectories today. History has the advantage of being specific rather than abstract–focusing on what actually happened, and the specifics of how it happened, could help open at least some people’s eyes to the inequities in our current reality.

Yes, history is a powerful teacher and I agree the history makes sense here. It is often difficult to get public audiences to sit still long enough to absorb the history of how we got ourselves here. For those who will hear it, let us tell that story. For the millions of others, more interested in what the Kardashians had for breakfast, we’ve got to get more strategic to get the message heard!

Thanks so much for your reply. Keep pushing!

I question the premise that poor messaging has caused the public to not support affordable housing. Virtually every recent affordable housing funding measure has been passed by voters. This has particularly been true in cities undergoing gentrification, like San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, Denver, Oakland, and many more. The messaging challenge is that the affordable housing crisis does not reach to the federal government, where the big dollars reside.

Thanks Randy for your reply.

Among the worst strategic errors made is using the term “low- and moderate-income.” That just plain scares people and generates opposition to housing for “low and moderate income” households. Instead, even though it doesn’t roll off the tongue, use the term “households with modest incomes” and — most importantly — speak of the types of households with modest incomes: teachers, social workers, seniors, recent college graduates, physical therapists, nurses, government employees, etc. In other words, humanize the people who need this housing. I can report from actual experience as senior planner in Oak Park, IL many moons ago that we successfully diffused the opposition to low- and moderate-income housing in large part due to an understanding reporter whose front page article spoke of teachers, etc who needed affordable housing to remain in the community. The term “low and moderate income” didn’t appear until the second page of the article.

On the Narrative of Mobility – there is a thing called “cultural attachment” that ties people to place. It evolves through kinship, relationships and routines, and results in a sense of belonging, or community. It is also a key component of resiliency. In today’s increasingly mobile society, cultural attachment is diminishing, along with resiliency, contributing to the complacency that leads to the narrative of mobility.

Here in the City Heights neighborhood of San Diego, where we have a large refugee population of people who have been displaced from their Countries (yet alone their homes), we are embarking on a campaign of “Here to Stay”, rooted in the concept of cultural attachment.

Thank you for championing this message! The challenge is: How can we coordinate the roll-out of these ideas as an initiative?

There is an article that I love that challenges the idea that many white urbanists who love living in mixed racial and income neighborhoods are themselves unintentional gentrifiers. It’s called, “Gentrifier? Who, Me? Interrogating the Gentrifier in the Mirror.” https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-2427.12067/full

Hey Allyson. I read this article with interest and came across your comment. Our message was not to white urbanists suggesting that they could be white gentrifiers. It was to urbanists suggesting that they are gentrifiers. Only as a means to and end: to complexify the conversation. We did a much better job of that in our 2017 book Gentrifier.

I am grateful that you found our article helpful.

I just read my comment, and the article doesn’t challenge the idea. Rather, it challenges white urbanists to interrogate their role as unintentional gentrifiers.

If gentrification could be made to work to the advantage of the people already in the neighborhood, it would be a good thing. The new residents will have more clout to push for better services and better schools. Crime should decline also. If only this could work to the advantage of both New and old.

To be frank, if we had a totally libertarian free market land use policy, with landowners being the decision makers on how their land is to be used, I’d have more sympathy with the “you don’t get to live here” meme. But we don’t. City Hall decides, not the landowners.

There is a deeply ingrained societal bias toward property owners which is systemic and self-reinforcing – and/or an animus toward those without property, which has prevailed in this country since Day One.

The Fifth Amendment guarantees property owners due process before government can take their property, as well as just compensation upon taking their property. Those without property have only an insecure right to acquire property, which government can and often does infringe with impunity and without recourse.

Workers who will never be able to own a home subsidize homeowners with their tax dollars.

The narratives above don’t work for those without property, but are powerful when employed by property owners: Proposition 13 was a collective voter decision that homeowners should not have to move just because newcomers with more money came to town and drove up assessments.

So I ask, it is possible to frame a narrative in a way that affords renters meaningful protections against displacement?