Phil and Jo Schiffbauer, via flickr, CC BY 2.0

It is often convenient to blame city planners for the affordable housing crisis. After all, those affected have no other public forum to vent their concerns, least of all toward those who are profiting off the crisis on a project-by-project basis. Sadly, this blame is often misguided because planners do not produce housing.

A case study of the profit-maximizing, decision-making that is driving the affordability crisis is downtown San Diego. Construction cranes are up all over, and a $6.4 billion development juggernaut is rolling through. Nearly 10,000 new units have been permitted by the downtown planning board over the last four years, and the fast and generous permit approval process is cited as a model by developers for other regions. Underlying this process is a programmatic master plan that eliminates the need for project-level environmental review, lax standards on deviations from the zoning code, and a public hearing process that is limited to design review, often bypassing complex questions about density and community impacts. The process is overlaid with myriad incentives in the form of density bonuses for affordable housing and green building.

This kind of permit streamlining that supply-siders clamor for in state and local legislation for land-use planning and zoning reform is a developers’ dream come true. Yet, this same socially blind approach to planning has led to more affordable housing units being demolished than being built, and a 60 percent spike in unsheltered homeless downtown in the last two years. This is compounded by the fact that with the dissolution of redevelopment in California, there is no requirement that 15 percent of the housing stock within downtown be set aside for affordable housing, and no requirement that 20 percent of the tax increment generated in that area fund affordable housing.

Some believe that the affordable housing crisis is caused by a supply shortage that will be solved by allowing any housing to be built with fewer restrictions. That is simply not happening in downtown San Diego.

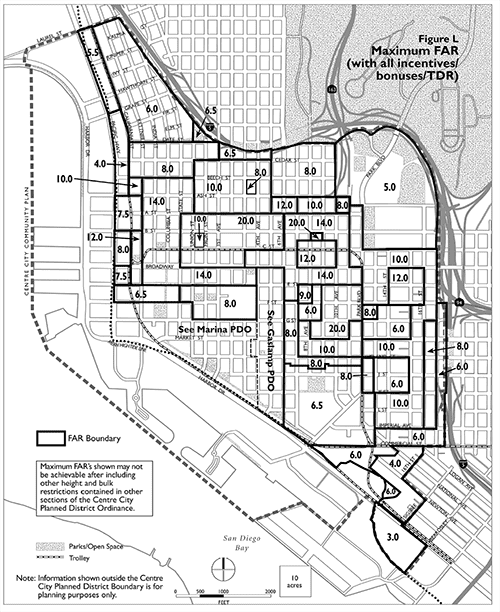

Downtown’s zoning plan has generous development entitlements, incentives, and bonuses. Courtesy of the City of San Diego.

Here are some key findings from my analysis of 36 projects approved by the board from 2013 to 2016, totaling almost 9,300 housing units in downtown San Diego:

- Over 90 percent of the housing units permitted were not affordable. Without affordability restrictions, developers and landlords can charge any rent/price they want, even for smaller units. For example, a recently built condo project has a starting price of $1.1 million with units at about 1,300 square feet at the lower range.

- 13 projects had affordable units, of which 8 had inclusionary housing units within them. Of these projects, three were under redevelopment agency agreements and at least another two utilized redevelopment funds.

- Six projects utilized the affordable housing density bonus.

I’ve had a front seat to the permitting process by serving on downtown San Diego’s planning board for almost three years. Here are three personal observations that may shed light on the mystery of why—despite creating every incentive that planners can conceive—we are failing to produce affordable housing at the level we need.

1. First, developers preferred to pay an “in lieu fee” rather than build inclusionary onsite. This may have to do with a lower pricing of the fee, so that it was cheaper to pay the fee than to build the units. One exception is that when redevelopment (or some other public) funds were used, this raises the importance of revenue sources to subsidize production of affordable housing. However, absent a requirement that the units actually be produced, downtown is going to continue to generate a fewer share of affordable units as land becomes more expensive.

2. Affordable housing units were mostly included in projects that could not utilize the standard streamlined process of approval. This is because they either involved a redevelopment agreement, a public right-of-way easement, a historical resource demolition, or some similar issue that needed additional review by a public body (such as the City Council) that would possibly consider the community impacts of a project. It is noteworthy that most affordable housing projects actually go through a more discretionary review process, oftentimes because they utilize public funds. Thus, streamlining the market-rate projects in comparison may do little to benefit the production of affordable housing.

3. Contrary to the misconception that more density begets more affordable units, this did not occur on a project-specific level. Developers would utilize the floor-area ratio only to the extent that the construction type and unit mix would maximize their returns—and would stop there. Out of the 36 projects approved, 30 did not utilize their maximum allowable floor-area ratio. That is roughly 45 percent density left on the table, for all the projects combined. Only one in six projects utilized the density bonus incentive by providing affordable housing onsite, and only to the extent that they were meeting the city’s inclusionary housing requirement, not a single unit more. With some exceptions, for example, a project within the airport’s flight path that could not be fully built out, the rational explanation that developers were not building to capacity is that there is an over-abundance of development rights in downtown, which makes development incentives for building affordable housing less attractive.

The net result is that downtown San Diego has been failing to generate 15 percent affordable housing stock in the last few years.

In a past post, I wrote that the real reason affordable housing isn’t being built in high-demand areas in California is that urban land values are too high. Downtown San Diego’s experience shows that laissez-faire streamlining cannot substitute for performance under regulatory requirements and public funds. Developers’ interests are to increase rents and prices, and they do not necessarily align with the public policy interest in lowering housing costs at levels that are commensurate with family incomes.

What’s going on in the rest of San Diego? I’m not sure you can isolate downtown from the rest of the city.

It seems like you’re arguing against a strawman here—does anyone actually believe that simply lowering the barriers to new development will produce affordable (i.e. below market rate) units? I think a better way to understand this issue is in terms of short- and long-term solutions to the affordability crisis. The only long-term solution is to build more housing, preferably close to where people work and high-capacity transit. In the short term, that is not sufficient, which is why there needs to be continuous and robust public investment in affordable housing creation and preservation. Both building more housing generally and investing in affordable housing specifically, are necessary to dig us out of the hole we’re in.

You raise many important points:

First, developers are not maximizing their FAR or filling the zoning envelope. It is incumbent on the permitting officials that they deny permits to developers who do not fill the zoning envelope.

Second, new development is not improving the affordable housing situation because much new luxury development replaces existing affordable units. Unfortunately, California’s property tax and Proposition 13 exacerbate this situation. Artificial limits on assessments encourage land speculation that drives up land prices. Proposition 13 is very destructive. It must be repealed.

This is a bizarre and difficult to follow argument. I don’t know the San Diego Planning Context in detail – though I do know they just legislated more density for more affordable housing (above the State Law) – which makes me presume developers are interested in increased density.

Otherwise this sounds like a series of critiques of SD’s zoning controls. Fix them! Make density minimums. Create incentives for projects to build the units instead of pay affordable housing fees. Ban demolition of existing affordable units unless they are replaced. Get some tenants rights tied to that.

I don’t see a critique of reduced process, rather it seems the author doesn’t like the results of the rules SD has in place.

Appreciate the thoughtful comments to this post. Some here are noteworthy, and need further discussion:

(1) I agree that in the long-term the supply of housing needs to be commensurate with the demand from population and jobs growth. The intent of this post is not to create a “straw man” argument that more housing equals affordable housing, rather it is directed at the policy front in California that is focused on housing supply deregulation regardless of affordability, using affordability crisis as the selling point for achieving that goal. This post questions the promise of housing affordability resulting from the market-based supply of housing.

(2) The case study of downtown San Diego as presented here is unique to this regulatory and governance structure. No two markets are the same, least of all in land development. Real estate regulations are idiosyncratic in their impacts, as an extension of real estate itself being idiosyncratic. It is therefore pertinent to ask why “regulations” as a generic concept are the bogeyman of developers, and why state and federal intervention into these purported “regulations” is such a priority in the promise of affordable housing? Why is it that regulatory streamlining appears #1 in most policy to-do lists for housing affordability, without empirical evidence that supports such claims? Why is it that market-rate developers and landlords push back heavily against regulatory requirements on rents and prices?

These questions are important because bundled among the targeted “regulations” may be those that ensure affordable housing be preserved, financed and built. I hope that this post spurs further discussion on the regulatory impacts on affordable housing, and precipitate a nuanced understanding of those regulations that actually further the affordable housing stock.

Murtaza,

I recognize just how intense the conflict is around these topics so I was nervous about trying to write a nuanced account. I worried that in an environment where people are locked into name calling, any attempt to say that there was something that we could learn from the ‘other side’ might be seen as some kind of betrayal. So I am hoping that you can understand why I am demoralized by your linking to my blog post with this description: “Some believe that the affordable housing crisis is caused by a supply shortage that will be solved by allowing any housing to be built with fewer restrictions.

That is not what I believe and not what I argue in this post. I say in the first paragraph “exclusively building luxury housing is no strategy for addressing the housing problems of low-income or even middle-income people.” And then “For low-income residents in high cost areas, there is no substitute for public sector action to provide below-market rate housing” and also “regulation is not the problem.”

I spend all of my time working for exactly the kind of strong requirements that you are calling for but I am not sure how we are going to build public support for more investment in affordable housing if we refuse to even allow discussion of why the market is building less middle income housing than is needed. I don’t see it as an either/or choice.

This entire article is predicated on the idea that it’s easy to build housing in San Diego, which is patently false. Just like it is virtually everywhere else in California. No one’s arguing that streamlining housing development by itself will fix all of our problems.

That said, when it takes literally years to go from project proposal to ground-breaking, we’re very, very far away from a “streamlined” or “developer-friendly” process. Show me a city that’s actually making it easier to build today than it was to build 20 to 40 years ago, and I’ll show you a city that’s affordable without subsidies.

Again, that’s not to say that we can just take a San Diego or Los Angeles, open up the city to a blitz of development, and suddenly have an affordable market. But the fact that we restricted things for so long is the biggest reason why we are where we’re at today, cost-wise, and the idea that any of these cities are actually development-friendly is so out of touch that it’s impossible to take any of this seriously.