Students participate in a college campus visit as part of the Indiana Promise program. Photo courtesy of Indiana Promise

College costs are escalating. Tuition and fees rose faster than inflation again last year, according to Money magazine, and financial aid isn’t keeping pace. Stories about graduates weighed down by huge amounts of student loan debt are becoming routine, and low-income students in particular seem to be targeted by predatory for-profit universities and loans to cover them. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Massachusetts, has weighed in on reforming student loans, and Sen. Bernie Sanders, D-Vermont, has raised the prospect of tuition-free public universities. In this environment, it’s hard to blame any non-wealthy family for feeling like college might be out of reach, even as the lack of a degree becomes ever more a barrier to economic security.

But into this environment steps the undauntedly optimistic children’s savings accounts movement, advocating for all children to have accounts dedicated to higher education, from an early age, with incentives to put money aside toward that goal. Plenty of people have proven that low-income families can save—but are the amounts they can save really going to make a difference?

How Do They Work?

While the programs currently in place vary a lot, the idea behind a child savings account is to create a vehicle in which a student, family, and third parties can make deposits toward the goal of helping to pay for post–high school education. The accounts are started with a seed deposit, and often come with incentive matches to encourage further savings—sometimes rewards for saving as little as $10 a month. Many programs also incorporate training programs that support families in improving their financial capability and understanding the financial aid and college application process.

SEED, or Savings for Education, Entrepreneurship, and Downpayment Initiative, was a 10-year, multimillion-dollar “national policy, practice, and research endeavor to develop, test, inform, and promote matched savings accounts and financial education for children and youth” that ran from 2003 to 2013. Participants saved an average of $30 per quarter, which, if continued (along with matches throughout a student’s education) could lead to an ability to pay for a year or two of community college. But many participants saved much less. “We don’t account for our history around not being savers,” says William Elliott III, director of the Center on Assets, Education, and Inclusion at the University of Kansas, and one of the leading researchers on children’s savings accounts. “It will take a while to change the behaviors we want to see changed. We have to allow programs some time.”

And yet, the CSA movement is arguing that the presence of a college savings account can be transformative, even at small dollar amounts. Oft-quoted research from the Assets and Education Initiative at the University of Kansas in 2013 found that students with college savings, even if it didn’t exceed $500, increased the likelihood of a student enrolling in college by three times, and completing it by four times, compared to having no dedicated college savings. (The research did attempt to control for the possibility that those more likely to go to college for other reasons would also be more likely to save for it.)

Researchers surmise that the way these small-dollar effects work is something called “identity-based motivation.” In other words, having college savings, even a very small amount of it, can change expectations—of parents, students, and teachers—especially if other peers are also participating.

We want kids to “discover who they can be, before they can limit themselves by who they think they are,” says Clint Kugler, CEO of Wabash County YMCA in Indiana, who launched a local CSA project that has grown into Promise Indiana. “Hope is a better predictor of success than test scores or attendance. How do we build hope for kids?”

“I wasn’t sure if it was possible to pay for college on my own and I had almost given up hope,” Dena Jo Squyres, a teenage CSA participant from Oklahoma told CFED. “However, now, thanks to the SEED program, I am well on my way to saving for college.”

The SEED program was, according to CFED’s website, “designed to set the stage for a universal, progressive American policy for asset building among children, youth, and families.” CFED has continued to advocate for exactly that, and its ongoing efforts to support, fund, publicize, and advocate for CSAs have gone a long way toward raising their profile nationally.

(Despite the drumbeat on “college” throughout the CSA movement, it’s worth noting that even with financial barriers fully removed, not every student would do well at, or want to attend, a four-year bachelor’s degree program. CSA programs, however, can be used for any type of accredited post-secondary education—public or private, community college, or a wide variety of certificate and vocational training programs.)

One Goal, Many Paths

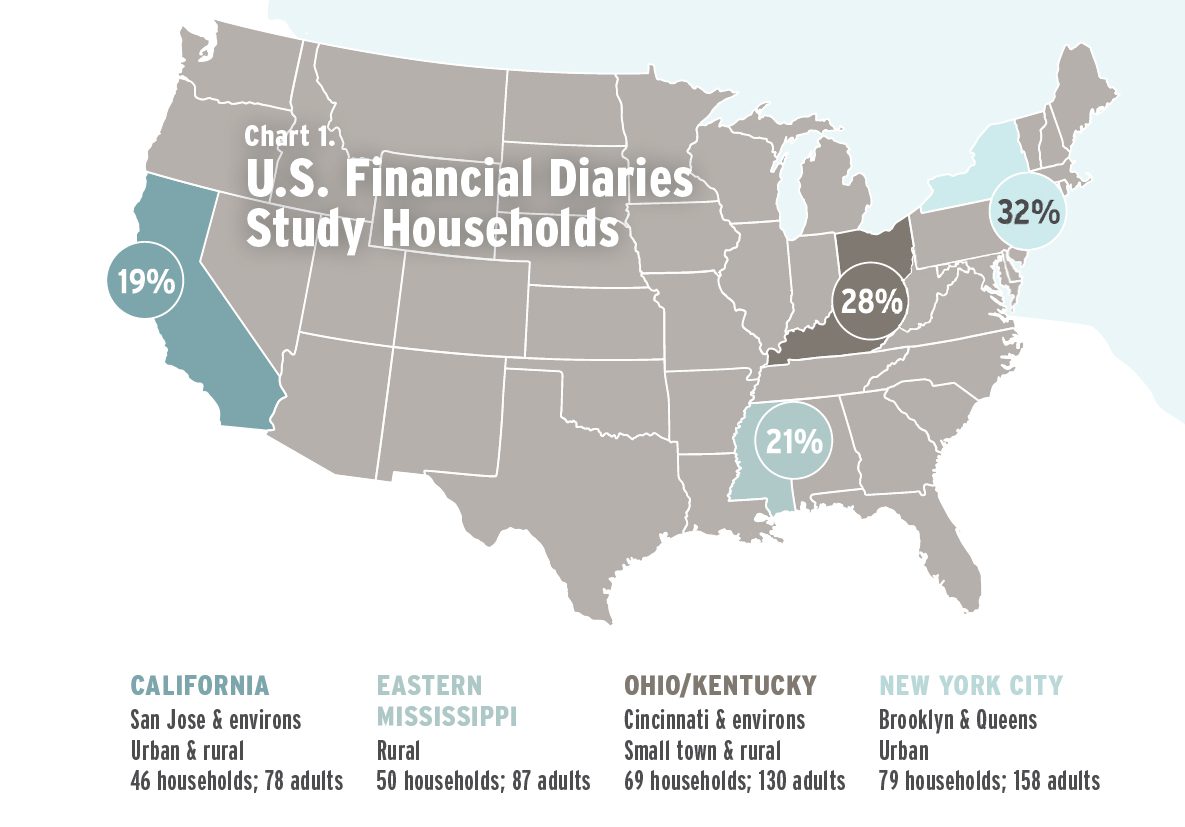

As of this writing there are about four dozen children’s savings account programs in the United States, and despite common goals, they vary widely on many details of implementation.

For example, some start at birth. The statewide programs in Rhode Island and Maine, for example, set aside a seed deposit for every baby born in the state. Many start when a child is registered for kindergarten, making the accounts part and parcel of a child’s whole formal schooling experience. Most of them aim to kick in well before families would traditionally think about college, because the idea is to create a college-bound identity from the get-go, affecting academic performance and choices all along the way, and preventing the creeping feeling that college is inaccessible. “We don’t want people to say ‘That’s great, but that’s not for me,’” says Colleen Quint, president and CEO at the Alfond Scholarship Foundation, which awards $500 to every baby born in Maine.

On the other end of the spectrum, however, is Inversant. With savings matches as high as one to one if participants meet certain goals, Inversant has helped 800 families save $700,000 toward higher education. But its programs don’t kick in until high school. They would like to start younger, but as an opt-in program, Yiming Shuang, Inversant’s director of operations, says they’ve had trouble generating commitment earlier. “Low-income households have higher vulnerability; it’s harder to lock money away in an account. In high school, they are more motivated,” she says. Nonetheless, by starting in ninth grade, Inversant is still working with families earlier than the typical junior- and senior-year financial aid and scholarship assistance programs.

Whether programs are automatic or require some sort of sign-up is also a matter of much conversation. When Maine’s Alfond Scholarship started, it was an opt-in program. But getting new parents to sign up for an account to accept the money was a huge amount of work, says Quint. “In the first five years, there was a lot of outreach to families,” she recalls. “A lot of our energy, 80 to 85 percent, was going to enrollment. And we had a 40 percent take rate. It was far short of what we were hoping for.”

So the group figured out a way to do it automatically instead. To make individual accounts, the foundation would have needed social security numbers, so it instead created a single omnibus account, and makes deposits to it based on the number of babies born. Statements associated with birth records track the amount owed to each child as it grows. Now, truly, all kids can benefit from the program, and the foundation’s energy goes toward informing and engaging families—sending statements that show their investment’s growth, encouraging them to create an account of their own to add to their savings, and giving them information about college.

Rhode Island, too, holds its program’s $100 seed deposit in an omnibus account, after an initial attempt to have families set up their own accounts generated very little uptake. Though they do technically still require an opt in, it’s as low of a bar as they can think of—simply checking a “Do you want $100 for your child?” box on the birth certificate form at the hospital. Heather Hudson, policy advisor to the governor, and former director of financial empowerment in the state’s treasurer’s office when this program was being created, saw the check box as a matter of empowerment: “Let them make the decision about whether they are willing.” On the other hand, even that box does lead to attrition, she says. “Some people see a dollar sign and think that checking means they’ll be charged $100. How do you explain it in a way that makes it clear that it isn’t a scam?” They get just above 50 percent of new parents to sign up.

Promise Indiana’s local programs also try for a low barrier to entry, making sign-up for the program part of the routine of registering for school, along with bus transportation and school lunch. They’ve achieved a 70 percent sign-up rate.

The question of where to put the savings comes up even for programs that are not automatic and universal. A federally tax-advantaged college savings plan already exists—known as the 529 account. But those who are taking advantage of them are heavily skewed toward the most wealthy.

Many children’s savings accounts programs try to walk their lower-income participants through setting up a 529 account either as a first or later step, but they say it’s a very challenging process. The forms are pages and pages long, with dozens of pages of fine print disclosures. They require social security numbers (or lots of extra hoops for those here legally without one) and proof of residence, which can be hard to obtain for people who have moved often. “Every time you introduce something like that you lose people,” says Quint, whose organization has been working with local partners to walk people through the process of setting up a 529 account. “If you are doing it on your own, that can be a struggle.”

Indeed, Cuyahoga County in Ohio found that out the hard way. They recently repealed their CSA program, because new parents had to open a 529 account within a year in order to claim the $100 seed deposit set aside for them, something that only 400 out of 10,500 eligible families accomplished.

Even once you have a 529 account open, most don’t accept deposits of cash or even money orders, notes Shuang, and sometimes you have to go through three steps on the phone before reaching an option to speak to someone in a language other than English. Also there are often minimum deposit amounts of $25 or more that are above what CSA programs target—many of which provide incentive matches to get participants to save steadily in increments of as little as $10.

That’s why Inversant has abandoned the 529 account and chosen instead to work with local credit unions. “When we say we’re going to open a Metro Credit Union account [our participants] feel safe,” says Shuang.

Still, having a consistent national account type for higher education savings makes sense, prompting some CSA advocates to call for changes to make the 529 account more accessible, so local programs can build off a common infrastructure. Benita Melton, program director for education at the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, a longtime CSA supporter and funder, suggests perhaps we can “‘CSAize’ the 529 system” with “automatic enrollments, seed deposits, matching incentives. Adapt the existing plumbing.”

And then, of course, there’s the question of the money. Funding for seed deposits, incentive matches, and administering the programs’ various outreach and educational activities comes from a variety of sources. In Maine, seed deposits are solely funded by a private foundation, with other philanthropies supporting outreach and programming. Inversant by Bob Hildreath, a wealthy businessman with an interest in helping immigrants, who contributed initial funding himself. Vermont’s program uses a combination of public funds and corporate philanthropy, while San Francisco’s K2C $50 seed deposits come from the city. Rhode Island’s is funded by a vendor who manages all the state’s 529 accounts as part of its contract. (A reasonable deal since the odds are it will increase the number of accounts for them to manage over the long term.) Promise Indiana’s programs have statewide support from the state’s 529 plan, the Lilly Endowment, the YMCA, and a hospital chain, Parkview Health. But as the program sets up in a specific school district (it’s currently in eight), it always requires matches by local resources such as community foundations and members of the business community.

The size of seed deposits and matches can vary widely. SEED OK, a one-year pilot for research purposes, gave a seed deposit of $1,000 to half of the babies born in 2007 in Oklahoma, and offered income-targeted savings matches of up to $250 every year through 2011. Promise Indiana accounts start with only $25, but the program works very intensely and directly with all participants.

Promise Indiana’s programs are exceedingly high touch, however. Each participating school district incorporates classroom programs to build a college-bound identity and take kids to visit college campuses as early as fourth grade. On the savings side, they actively work with students to identify “champions” in their lives (relatives, family friends, etc.) and solicit them to contribute to their accounts, in order to earn savings matches. Teachers and principals identify those who “have a gap in [their] champion circle” and look for volunteers to “weave into their lives,” explains Kugler. In one school, for example, kids have been connected with a local nursing home and visit their “champions” there. Beyond the money, getting contributions from champions makes children feel like the community is supporting them. “When a 6 year old says, ‘I want to be a journalist. Will you give me $5 for my college savings account?’, if that kid was selling a candy bar, you might buy it,” Kugler says. “Now imagine the power if the person says, ‘Yes, I will make a donation, and let me tell you why. People believe in you. [The] community believes in you.’”

It’s not just about the kids either. Inversant, which has programs in four Massachusetts cities, combines its savings rewards with a multiyear curriculum of learning circles covering “a full range of college access topics.” Through these programs and one-on-one support, parents—many of whom are immigrants—become more engaged in their children’s education. “A lot of immigrant parents didn’t feel comfortable going to [their children’s school],” says Shuang. “They don’t know what questions to ask. We provide a safe place to say, ‘I don’t know what GPA is.’ Now they know. Families feel more active and empowered to play a part in their students’ education.”

In the more universal programs, such as Maine’s and Rhode Island’s, the scale is much bigger, and so the outreach is, by necessity, a bit more hands-off, taking the form of printed materials, such as mailings with statements on how the accounts are doing, combined with tips about supporting kids in school, financial security, and looking ahead to college. Local partners then take on more high-touch work on a smaller scale, as when a Head Start program holds events to help families create a 529 account.

Next Step: Wealth Transfer

Low-income families can save—but the amounts are still small. Even with incentive matches and a decade or more of interest, many CSA participants will end up with only several hundred to a few thousand dollars.

It’s clear this still has an effect on both hope and college preparation, which in turn influence access to scholarships and financial aid. But in the end, many college options are still vastly more expensive than the amounts that most lower-income families will be able to save.

CSA supporters are clear that they are only one tool in a toolbox that includes academic support, reducing the cost of college, and reforming financial aid to make it more targeted and more accessible. Elliott, among others, also suggests that using CSAs as a vehicle for larger wealth transfers should also be on the table. He draws on his research into college debt in discussing this dynamic, in which he found “if you had less assets growing up, you get less return on that degree. College debt can have negative effects on long-term wealth accumulation and on the ability of education to act as an equalizer.” He therefore feels that changing that asset disparity up front will be what unlocks the potential of higher education.

“If we need assets to let education be an equalizer, just free college alone won’t be enough if you want to cure poverty,” he says. “Free college sounds great, but there are different ways to get it to free.”

This is why Elliott and some others see children’s savings accounts as vehicles not only to encourage savings, but to facilitate larger wealth transfers by redirecting some portion of existing scholarships and even Pell Grants into CSAs much earlier in a student’s life. Putting these assets directly under the control of students earlier makes them feel in control of the process, says Elliott. And “having that money early on signals that society has invested in us.”

Kids who currently get scholarships at the end of high school tend to have already had more advantages, points out Melton. “What if we flipped that on its head,” she asks, “and distributed scholarships early to incentivize certain milestones that are associated with increasing high school graduation and college preparation?” Promise Indiana programs are starting to do this, with various matches associated with not only meeting savings goals, but also meeting individually designated academic goals or participating in financial preparation classes. “I like to characterize it as keeping kids pointed north on their educational path,” says Melton.

Will They Work?

There’s not enough research yet to know how the different choices in program styles affect the outcome. And with such a long time horizon, it’s going to take a while to know just how much these programs are actually changing college attendance and completion rates. That’s why Elliott and others are working on a set of interim measures that predict college success—such as socio-emotional skills, academic goals, and parental expectations—which can be used for shorter-term evaluation of the programs. For example, “research from SEED OK indicates that younger children who were randomly assigned to receive CSAs demonstrated significantly higher socio-emotional skills at age 4 than their counterparts who had not received a CSA,” wrote Elliott and Anthony Poore of the Federal Reserve of Boston in a CFED blog post. Since there is a “strong correlation between socio-emotional development and academic achievement,” they suggest this could be one potential interim measure for evaluating CSAs.

“You need to give policymakers the opportunity to defend this allocation of resources,” says Poore. “Our political patience doesn’t extend 18 years; it usually extends 18 months if you’re lucky.” So interim measures will be crucial.

Nonetheless, in an exceedingly politically polarized time, CSAs also benefit from a baseline measure of appeal across political differences. The National Aspire Act, one of the first attempts to create a national children’s savings account program with a federal seed deposit, had bipartisan support, and featured Sens. Chuck Schumer, D-New York, and Rick Santorum, R-Pennsylvania, as co-sponsors. “The idea of people investing in themselves resonates on both sides of the aisle,” says Poore.

“It’s a hard idea to get on the wrong side of,” Melton agrees. “Who is going to say, ‘I don’t like that’?”

Comments