Photo courtesy of King Park CDC

The tenants of Warren Hall fear they have run out of options. Many have lived in the 33-unit building in the once-low-rent Boston neighborhood of Brighton for decades. Warren Hall’s owner participated in the Section 236 program, a housing affordability program that dates back to the Great Society. Section 236 established a network of subsidies and tax incentives to building owners, who also received 40-year mortgages, and in exchange had to keep rents priced affordably for low- to moderate-income families.

This section of Brighton has seen its fortunes change along with the rest of the city. After struggling through the mid-century urban crisis, early 21st century Boston is one of America’s hottest housing markets. There are few neighborhoods in the city that haven’t been affected, and the western Brighton section-sandwiched between Cambridge to the north and Brookline to the south-is no exception.

And like the rest of the buildings in the 236 program, Warren Hall has reached the end of its 40-year mortgage term and its accompanying rent restrictions; and its owners, New York-based real estate firm the Olnick Organization, want to cash in. After years of wrangling with Olnick and seeking some way to keep their rents from rising, the tenants have run out of options.

“As a person with a disability, I have lived most of my adult life in affordable housing. I had never heard of the fact that subsidies could end,” says Karen Carson, head of the tenants council in Warren Hall. “They are going to turn this building into condos or market rent. I didn’t realize that could happen to all this housing built back in the 1970s and 1980s. When I found out it was expiring, I got pretty scared of becoming homeless.”

Carson estimates that the tenants, many of whom are elderly, have about one more year in their homes. (Olnick didn’t file its paperwork correctly, so when they initially tried to end affordability restrictions the tenants were able to forestall the process.) She doesn’t know what she will do when Warren Hill will be too expensive to call home anymore.

“If you can afford $2,000 a month you’ll have no problems finding rent[al housing],” says Carson. “But if you are 65 and retired and living on a fixed income, you aren’t going to be able to move. There are no openings anywhere.”

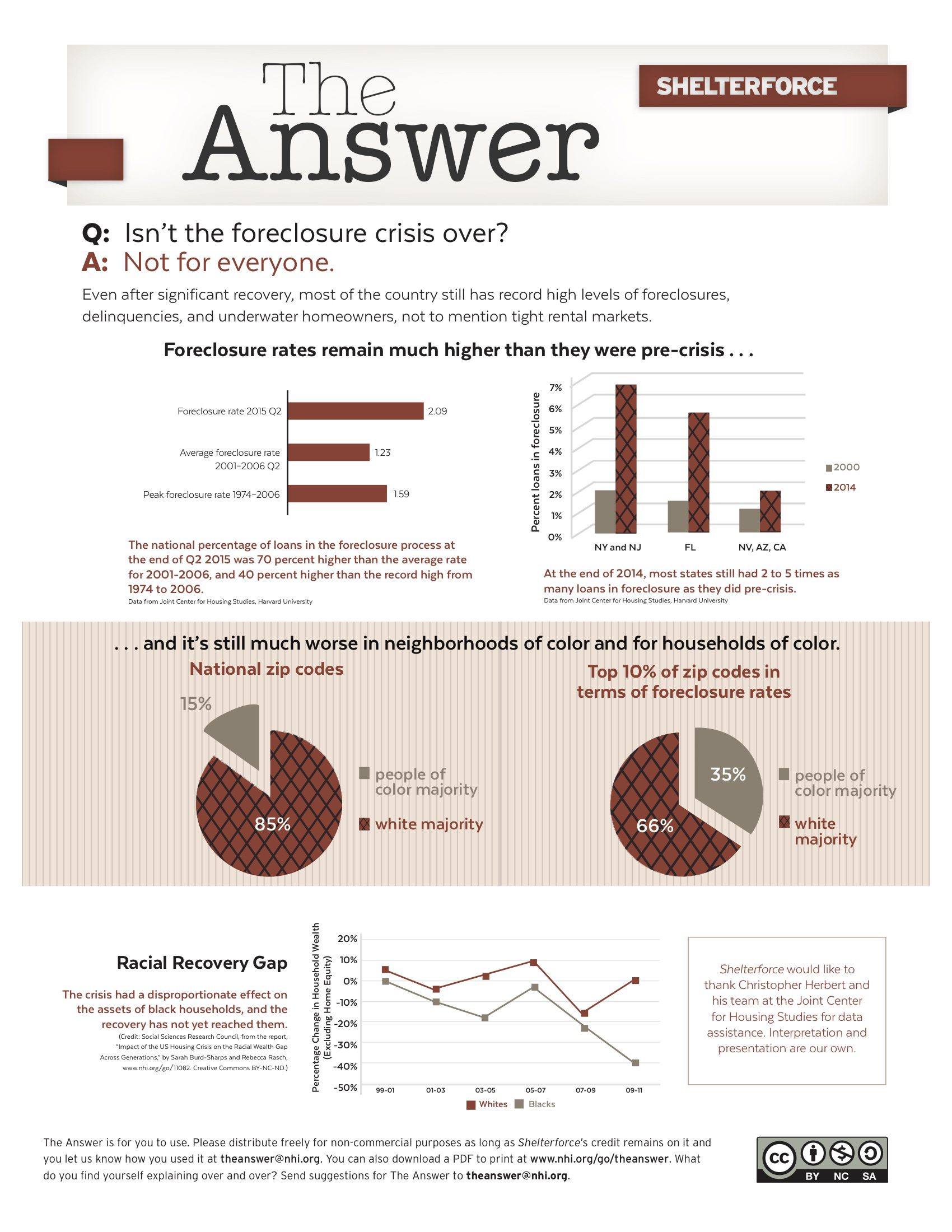

The Affordability Churn

America’s housing crisis is inarguable. As of 2014, home ownership is at its lowest level since 1967 and the rates have continued to fall during the first two quarters of 2015, exacerbating the affordability crisis. If rental markets were healthy, declining home-ownership wouldn’t necessarily be cause for alarm. But as the number of renters has increased, new units have not been created at a rapid enough clip, thus rents have risen sharply. Earlier this year, Enterprise Community Partners found that 25 percent of renters spend half their income on housing costs, while Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies found that in 2013 half of renters spent over 30 percent of their income on housing.

America’s affordable housing policy is not coming close to meeting the needs. Rental assistance is so underfunded that only 1 in 4 households that are eligible for it actually receive it. (Meanwhile, more than half of federal government spending on housing goes towards households that earn more than $100,000 a year, according to a 2013 analysis by the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities.)

Federal funds for affordable rental and home-ownership programs have largely stagnated or declined. Urban Institute analyst Brett Theodos estimates that the two principal supports for homeownership, the CDBG and HOME programs, have been cut by two-thirds and one-half, respectively, since their peak. The Low Income Housing Tax Credit is indexed to population and holding steady, but it does not come close to meeting the need, while 100,000 Section 8 vouchers have been lost to Congressional budget cuts. Moving forward, White House requests for the 2016 budget are not especially generous and will no doubt be driven down by competing, and more austere, proposals from Congressional Republicans.

But looking at the number of subsidized affordable units being created doesn’t show the whole picture. All of these programs assure affordability for only a limited—and sometimes quite short time. After that period, public investment is lost, and needs to be spent again just to keep the affordable housing stock from shrinking, escalating the crisis even further.

“We can’t afford to lose a single unit of subsidized housing,” says John Davis, founder of Burlington Associates, a consulting firm that helps form and maintain community land trusts, a form of permanently affordable housing. “You have a steady loss of affordable units because of deterioration, demolition, and market conversion [after affordability periods end].” No city or county can afford to focus only on creating subsidized housing that will expire, argues Davis.

Rental Programs

At 40 years, the affordability restrictions on the 236 program were actually unusually long. That program was discontinued long ago, and pretty much all of the units built under it have reached the end of their 40-year deals. However, elsewhere in the rental market, other policies that supplanted the traditional public housing program, like project-based Section 8 and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, are still being built with time-limited affordability restrictions.

These units don’t necessarily lose their affordability the first time it’s possible to convert them to market rate. A 2015 study found that 71 percent of project-based Section 8 properties opted back in to the program when their affordability restrictions expired, for either another 5- or 20-year term, while only 4 percent, totaling 748 units, opted out. (Another 2 percent were foreclosed upon, while the other properties did not have contracts that expired in the 2005–2014 study period.) There were fewer opt-outs in the 2015 study than in a previous iteration published in 2006.

A 2012 study for HUD found that first-generation LIHTC properties often remained affordable even after the 15 years had elapsed, partly because they are often run by mission-driven nonprofits with no desire to convert, or because they are in cold real estate markets where most housing remains relatively affordable. The second largest group of properties underwent major re-capitalization using public funds, thus extending their affordability periods. And then the smallest group —still totaling 50,000 units—was repositioned as market-rate housing and ceases to operate as affordable.

“In general, owners who own tax credit properties, Section 8 properties, [or] government-assisted rental properties generally maintain those properties as affordable after the legal restrictions have expired,” says Michael Bodaken, executive director of the National Housing Trust.

But in the earlier years of these programs, the results were less cheery—and many advocates are concerned that another wave of opt-outs is coming. Tenant advocacy groups claim that between 360,000 and 400,000 units of project-based Section 8 have been lost since 1996, a greater blow to the affordable housing stock than the 60,000 to 100,000 units of public housing lost to HOPE VI conversions. The first low-income housing tax credit deals—the program was created in 1987—had similarly short provisions, with affordability limits lasting only 15 years. There is no research that shows exactly how many assisted units have been lost because of this short LIHTC window. But Congress apparently recognized the undesirability of such a brief period by extending affordability limits to 30 years for all projects initiated in 1990 or subsequent years. Some states have taken further action. In California, LIHTC programs come with an affordability requirement of 55 years, while states like Massachusetts, Michigan, and Vermont require perpetual affordability.

“In many gentrifying areas it is more likely that an owner will opt out,” says Bodaken.

Owners (especially for-profit landlords) are much more likely to opt out of Section 8 or not renew their LIHTC contract if they can get higher returns by entering the market, as they can in hot markets like Seattle, New York, San Francisco, Washington, D.C., and Boston, as well as in large swathes of metropolitan areas like Chicago, Los Angeles, and Austin. The greatest danger is the coming deadline when the 30-year LIHTC contracts near their end, which could mean the loss of 1 million units by 2020. The HUD study of the 15-year contracts downplays this worst-case scenario, but notes that those at greatest risk include the 51.5 percent of units in locations with middle- or upper-income census tracts—the very units that are the most valuable to lower-income families who are trying to live in safe and opportunity-adjacent neighborhoods.

Others seem more worried. Raphael Bostic, former HUD assistant secretary for policy development research, speaking to the National Community Land Trust Network conference in October, mentioned the expiring of both project-based Section 8 and tax credit units as serious upcoming challenges that could make “everything a whole lot worse.” Considering factors like market conditions and contract expiration, the Urban Institute has calculated that 33 percent, or 446,000 units, of just project-based rental assisted units are in imminent danger of losing their affordability status. “Congress doesn’t let HUD do new contracts,” Urban’s Erika Poethig told Bloomberg News. “Once a project is lost, it’s lost.”

Homeownership

Public investment has been put into affordable homeownership as well—and there the affordability periods tend to be even shorter, and the likelihood of a transition to market rate even greater.

Downtown Indianapolis and its surrounding neighborhoods went through the usual cycle of divestment and blight after World War II. Due to a quirk of history, the city managed to act like its Sunbelt counterparts, gobbling up its suburbs and gaining population in the face of widespread urban decline. But that expansion and prosperity obscured the suffering at the heart of Indianapolis. The center city and its surrounding walkable neighborhoods, even those well-stocked with Victorian homes, suffered an urban crisis familiar to residents of Boston or Buffalo.

By the 1990s, many neighborhoods around downtown were riddled with vacant lots and blighted properties. News stories on the recent redevelopment successes in Fall Creek Place, roughly 2.5 miles from center city, almost never fail to mention that the neighborhood was recently nicknamed “Dodge City” because of the frequency of gun crime, especially drive-bys. Then in 1998 Indianapolis won a $4 million Homeownership Zone grant from HUD, followed by $20 million in local dollars, allowing the city to acquire much of the blighted land and buildings. Some units were restored, those in the worst shape were leveled, and new units were built. The success of the project led to even more public investment from other public sources and, eventually, the private sector. Over the last 15 years 400 new and rehabilitated for-sale homes have been constructed and occupied in the area.

“It’s a significant amount of money in a small geographic area, six blocks by six blocks, with probably $40 million worth of public money going into those properties over the past 15 years,” says Steven Meyer, executive director at King Park Community Development Corporation, which has played an active role in the revitalization of the neighborhood. “I think it’s been wildly successful as far as redeveloping a neighborhood is concerned. But we are now facing an issue where there is very little affordable housing left in the area.”

In the first two phases of Fall Creek Place’s redevelopment, 51 percent of the houses constructed or rehabilitated were required to be sold to families earning less than 80 percent of the county’s median income. The later two phases didn’t have that mixed-income requirement. CDBG and HOME funds were routed into the area, and most purchasers of the homes designated for lower-income buyers received down payment assistance. In exchange, covenants were placed on the units: For 10 years they had to be owned and operated by a low-income tenant.

The last of the covenants will expire at the end of 2015, leaving almost the entire neighborhood at market rate. And now that Fall Creek Place is safe and stable, and downtown is bouncing back, low-income people can no longer afford to live there. Meyer says that King Park Community Development Corporation has begun to buy houses at market rate to sell at a lower price for lower-income residents. But the process is incredibly costly and necessarily limited to a few units—in fact, only one so far. Meyer doesn’t know the value of the original subsidies, but says that generally between $50,000 and $75,000 in CDBG or HOME grants is invested. At this point even with that amount of subsidy, the homes are not affordable to those earning less than 80 percent of the area median income.

“After the affordability period has expired on the last of these original houses, there will only be 11 affordable units in Fall Creek Place,” says Meyer, who estimates that at least 100 units had affordability covenants attached to them at one point.

The new units being built for phase four, none of which are affordably priced, are being sold in the $400,000 to $600,000 range. Housing from the first phase goes for $350,000 to $500,000, well beyond the reach of those at 80 percent or less of area median income. Those 100 units of down-payment-assisted housing helped the families that initially won them, but if they sold, the subsidies were lost. No new low-income families can take advantage of the amenities and services now available in Fall Creek Place.

And yet, “had you asked people 15 or 20 years ago when they started this project whether they expected there to be an affordability issue in 2015, for this neighborhood,” says Meyers, “you would have had a hard time” finding anybody that would have answered yes.

Stories like this are the norm in the world of affordable home-ownership. The Long Island Housing Partnership has started moving toward permanently affordable models after seeing similar problems. “When we originally started, it was 10-year restrictions and after those 10 years, [owners] were seeing the windfall profits, [so] they sold it on the open market,” says James Britz, senior vice president of LIHP. “We always said that was really hitting the lottery. Some appraised for $400,000, and we had sold them for $100,000.” Britz guesses that they’ve lost a couple hundred affordable homes this way, which is particularly painful in an environment where land is scarce and very expensive. “No one wants to be looking for land again,” says Britz. Early on, LIHP used a combination of HOME funds and now-defunct state-level program. If the restrictions had been in perpetuity, those public funds would still be doing their work. “Not having to put subsidy back in” is a huge deal, says Britz. “Every municipality across Long Island understands that.”

There is no way to tell precisely how many housing units have received subsidies to ensure that lower-income families can afford to purchase them. But it is fair to assume that the vast majority of subsidized affordable homeownership units can be sold at market rate prices by the first beneficiary because most programs only set affordability restrictions for a relatively short period of time. The HOME program, for instance, sets affordability limits of 5 years for less than $15,000, 10 years for $15,000 to $40,000, and 15 years for $40,000 or more. Few state, local, or nonprofit agencies even keep track of how many publicly funded homeownership units there are, let alone how many have been flipped to market rate or how many dollars of public money have been spent in this fashion.

The Ohio Housing Finance Agency and Oregon Housing and Community Services (also a state housing finance agency) do have some data. In 2014, OHCS awarded $750,000 in downpayment assistance funds to help 160 homeowners (who had to be at or below 80 percent of AMI). Of these homeowners, 10 were on a community land trust, called Proud Ground, and thus living in a permanently affordable unit, leaving 150 that can eventually sell at market rate.

Over the past 15 years, the Ohio Housing Finance Agency’s downpayment assistance program has spent $21.7 million to assist homeowners in purchasing 479 units. Most of the sales occurred in the first five years of the program, because after 2008 much of the funding dried up, and it became harder to find people at 80 percent of area median income who were in any position to buy a house. Once a buyer receives assistance, a 10-year second mortgage is put on the home. A certain percentage of this mortgage is forgiven every year until the 10th, when it is completely forgiven. If the owners sell before that, they have to repay the subsidy.

“We don’t do any tracking after [the units] are sold except for that mortgage that stays on the property,” says Sean Thomas, chief of staff of the Ohio Housing Finance Agency. “It’s one of the research things on our to-do list, to go back and pull all the records and see if the current resident matches the resident who bought the house. But we don’t do any monitoring on these for-sale homes after they are sold, except between years one and ten.”

In Thomas’s experience, for now, most of those who sell get an even lower price than they first paid due to Ohio’s depressed housing markets. “For these specific programs there are not a lot of cases where we are concerned that if they sell they are going to flip to higher incomes,” he says. Of course they weren’t concerned about that in Indianapolis either.

Affordability Forever?

Expiring restrictions are not the only reason affordable housing is being lost. There’s also a lot of disinvestment, mostly in the private unassisted sector, says Bodaken, of the Housing Trust Fund.

But given the need, a growing number of advocates are arguing that it would be a much more efficient use of public funds to direct them toward units that will remain affordable. Though the cost of monitoring a permanently affordable unit is not zero, it is significantly lower than the costs of starting over from scratch, especially in a market that has appreciated.

Funding levels for affordable homeownership and rental alike have never been sufficient to meet the need, and most programs are shrinking rapidly, while others like LIHTC just keep steady. Meanwhile, if advocates are correct, 500,000 units of affordable housing in just the public housing and Section 8 project-based programs have been demolished or converted to market rate since 1990, when the need was far less than it is now. As long as access to resources is shrinking, the importance of permanent affordability is difficult to deny.

Creating incentives to re-enroll expiring units has been effective, but there are also ways to explicitly and intentionally make both ownership and rental units affordable for the long haul—either in perpetuity or close to it. In community land trusts, deed-restricted inclusionary housing units, and limited-equity cooperatives, for example, subsidy is left in for-sale homes through resale restrictions to make them always affordable to the next home buyer in the same income range. The Urban Institute has released two cross-site studies on programs like these and found that owners still made strong rates of return even while the affordability was being preserved. Ironically, however, it can be harder to get publicly supported financing for these types of programs than for programs through which the investment will later disappear. Rental units can also be kept affordable long term through a community land trust or deed restriction.

As the housing crisis worsens and budgets tighten, permanently affordable housing strategiesl—which combine the fiscal prudence of investments that keep working over the long haul with the social benefits of long-term housing stabilityl—could be poised to play a much bigger role in our housing policies.

Public agencies at all levels of government should review their regulations, funding priorities, and affordability periods with the long haul in mind. The alternative is to leave more and more of lower-income America’s families to the mercy of a free market that often proves incapable of providing worthwhile goods for the money they can afford to pay.

Shelterforce will be following up this article with more in-depth coverage on permanently affordable housing strategies, how they work, and how they can play a larger role in the housing market. Stay tuned! But in the meantime, check out some of our articles and blog posts on the topic.

Thanks for this thoughtful article, Jake. I agree that we’ve been careless with our subsidy. It would be interesting to estimate what the size of our affordable stock would be if we had required permanent instead of temporary affordability restrictions.

It surprises me that there’s such push back against permanently affordable housing since working people’s ability to access housing in the private market continues to decline.

Permanently affordable housing seems to me to be the most efficient use of taxpayer dollars; why isn’t the tea party demanding it?

It may be important to look at the Oakland land trust format. Cities need to just out source affordable housing to an organization that can maanage it. Or create an office that manages all the affordable units, making sure they stay affordable in perpetuity.