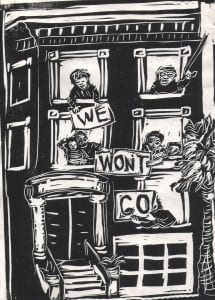

Graphic by Melissa Klein

On June 11, San Francisco’s united tenant and affordable housing advocates defeated the latest assault on San Francisco renters, turning potentially grievous legislation into an actual net gain for protecting the city’s limited rent-controlled housing stock.

The ordinance, as originally proposed by San Francisco supervisors Mark Farrell and Scott Wiener, would have allowed over 2,000 rent-controlled units to automatically become condominium units, bypassing the city’s annual 200-unit cap (which are awarded by lottery) by paying a fee of between $4,000 and $20,000 per unit. Not only would this have meant over 10 years worth of rent controlled stock being lost in one fell swoop, but the legislation would have set a precedent for doing away with the condo conversion cap altogether, further incentivizing evictions and buyouts of tenants now protected under San Francisco’s rent control laws.

Instead of just fighting the bill, housing advocates took a nuanced approach, proposing amendments that turned the effects of the original bill on its head, while still creating an opening for some apartment owners seeking to convert their units into condos.

The history of the renters’ battles in San Francisco helps explain how this fight came about, and how it was won.

Looking Back

Like many major U.S. cities, San Francisco has a 64.2 percent renter majority, falling in line with New York (69 percent), Los Angeles (63 percent), and Chicago, Houston, and Dallas (all about 55 percent). In the 1970s, after decades of relatively low rents—the result of post-war disinvestment, redlining, and white flight—San Francisco began to experience rising rents and home demolitions. A combination of regional planning efforts to re-envision San Francisco as a Pacific Rim finance capital, the intentional return of capital investment to the inner city after years of disinvestment, rising gas prices, and a new hipness to urban living spurred the beginning of San Francisco’s long curve of gentrification.

At the same time, a growing progressive political alliance was developing in San Francisco, convening in a Community Congress in 1975, with the central pieces of its platform being the election of the local legislative body by district rather than city-wide and a control on rents.

In 1978, California’s Proposition 13 capped property taxes in the state, and there was a resultant expectation that rents too would be limited. Proposition 13 limited property taxes to 1 percent of assessed value and limited increases in assessed value to 2 percent per year. A move by large apartment owners to raise rents despite their recent windfall on property taxes led to a renters’ revolt, which brought about San Francisco’s Rent Stabilization Ordinance in 1979. The law, locally called “rent control,” applies to most rental units built before 1979, and limits rent increases to a formula tied to the Consumer Price Index, about 1.5 percent per year. Approximately 145,000 units, or 70 percent of the city’s rental stock, are protected by rent control.

However, there are significant limits to this protection. San Francisco’s rent stabilization does not have vacancy control, so when a tenant moves, rent can be increased immediately to whatever “the market will bear,” after which, rent increases are again limited to the rent stabilization formula. A statewide law passed in 1996, the Costa-Hawkins Act, made it illegal to apply rent control to condominium units. This means that once a rental unit is converted to a condominium, it is no longer subject to rent control, even if it is maintained as a rental. Every condo-converted housing unit is one rent-controlled unit that the city will never get back.

San Francisco is by far one of the country’s most unaffordable rental markets. The National Low Income Housing Coalition ranked the city as having the second most expensive rental housing market, behind only Honolulu. One would have to earn $34.52 an hour, roughly $70,000 annually, to afford the average two-bedroom fair market rent. Further, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that “sizzling” rents steeply inclined in the last year, with one firm estimating an average of $3,437, up 21 percent from a year ago. People are forced to live with overcrowding, in shabby conditions in unsafe neighborhoods, and pay a huge percentage of their salary for rent in exchange for living in this city.

At the same time, rates of evictions are on the rise. The San Francisco Rent Board’s annual report on evictions, released in March, shows that no-fault evictions increased by 26 percent this year, with a total of 1,680 evictions. The highest increase was in “Ellis Act” evictions, which means the owner intends to take the unit off the market.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. In 1979, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed a Condominium Conversion Ordinance with the intent of balancing the goals of preserving the city’s limited stock of rental housing and allowing the occupants of rental buildings to become condominium owners. Following amendments in 1984, any two-unit building could be converted to condominiums, but only 200 three- to six-unit buildings could be converted per year, chosen through a lottery system. While the intent was to help tenants become owners of their units, only a third of the units in each building must be occupied by the owners at the time of the conversion. Larger apartment buildings cannot be converted into condominiums, though they may still be bought by groups of tenants and investors with a joint mortgage.

A new market has developed of these type of owners (called a “tenancy-in-common” or TIC), who buy a rental building collectively, move in, and apply for the condominium conversion lottery. While it’s hard to verify the exact correlation between sales of TICs and the waves of tenant evictions, it’s clear that there is a steep monetary incentive for real estate speculators to clear out buildings and sell to a group of TIC buyers who have bought in to the expectation that within a few years they will be able to convert and sell at a steep profit.

Moreover, somewhere around 40 percent of the total rent-controlled stock in the city is in the two- to six-unit buildings that are vulnerable to being converted and thus losing their rent-controlled status. Since 2000, about 516 rental apartment buildings become condominiums each year, never again to be rented out under rent control as the result of the 200 conversions per year of three- to six-unit buildings restricted by the lottery, plus over 300 conversions per year of two-unit buildings.

Since the original rent control and condo conversion laws were enacted, there have been numerous attempts to modify them. Attempts by landlords to tamper with the condo conversion ordinance lost repeatedly on the ballot, each time by an almost two-thirds margin. These attacks are rightly seen by voters as a backhanded way at weakening the city’s rent control law, with the ultimate goal of eventually doing away with it.

Building Compromise

Affordable housing advocates were successful in convincing the city’s Board of Supervisors and Mayor Edwin Lee to hold this latest threat, the condo conversion bypass fee legislation, until after last year’s November ballot, as it otherwise threatened to undermine the success of the Housing Trust Fund proposition on the ballot, which passed.

But it was on the agenda at the first hearing of the city’s board in January, and dozens of tenants and TIC owners spoke.

While it would be easy to make fun of the entitlement exhibited by some of the TIC owners at the hearing (one complained of the value he lost on his $1.5 million home, another complained of the difficulty of converting either her three-unit or her six-unit TIC, apparently indicating that she was a “tenant” in two different buildings), it became clear that TIC owners were facing some relative hardship as well. While in fact there were no foreclosures or defaults among the TIC owners (unlike many single-family homeowners in the city’s primarily people of color communities), the banking system had changed the rules of the game for TIC owners since the 2008 financial crisis.

The only financing available to most TIC owners had been three-, five-, and seven-year adjustable rate mortgages that needed to be refinanced within a few years. But after 2008, banks tightened their requirements, demanding higher credit scores and higher downpayments, which made refinancing much more difficult. These TIC owners wanted an exit strategy by being allowed to convert their properties to condos right away, thus making it easier to either refinance their loans or simply to cash in on the windfall of a condominium sale.

As they were questioned by one supervisor, however, it became apparent that many other supporters of the proposal at the hearing were not “real” TIC owners, but real estate lobbyists and property owners.

Meanwhile, tenant activists had organized to stop the legislation, pulling together a broad coalition of tenant advocates, affordable housing advocates, community organizations from renter districts, environmentalists, labor organizations and advocates for low-income populations. The campaign was led by a broad spectrum of the city’s housing justice organizations, including the San Francisco Tenants’ Union, Housing Rights Committee, Chinatown Community Development Center, AIDS Housing Alliance, Affordable Housing Alliance, the Council of Community Housing Organizations, Tenderloin Housing Clinic, Tenants Together, Eviction Defense Collaborative, Senior and Disability Action, and Causa Justa :: Just Cause.

The activists sat down with allies on the board of supervisors to amend the original condo conversion bypass proposal after realizing that there would not be enough support to kill it outright. The goal was make it hard to vote against by those who claimed to want to meet the purported intent of the proposal, which was to allow the current pool of TIC owners “clogging up” the system to convert quicker and easier than the lottery would allow.

The amendments contain critical tenant protection safeguards to stop the bypass from resulting in a spike in evictions: while they leave the expedited process for those stuck in the pool wanting to convert in place, they requires a suspension of all future conversions after that for a minimum of 10 years.

Under the amendments, after the initial backlog of 2,400 units are allowed to become condominiums, all future conversions will be suspended for at least the next decade, creating a cooling off period in the speculator-fueled condo conversion market. A supervisor from a moderate district suggested that length of the suspension should be linked to the city’s performance in building new affordable housing units to replace the lost rent controlled units. Affordable housing and tenant advocates jumped on his amendment. Every unit converted must be replaced with a new affordable unit and until that number is reached, the suspension continues. Also, the number must be above and beyond what is already anticipated by the city’s housing office.

When conversions are allowed to resume, they will be limited to four-unit buildings and smaller, and will require a majority of owner-occupancy tenants, emphasizing the idea that the conversions are really about creating pathways for tenants to become owners and not about real estate speculation.

The compromise was actually a hard pill to swallow for many housing and tenant advocates involved in the larger campaign. Campaign steering committee members bristled at the very idea of negotiating and worried that there would be no way to truly protect tenants from evictions and guard against spurring real estate speculation. This was also true of some of the progressive city supervisors. One announced at a press conference detailing the new legislation that he would vote against it if it were watered down by even a degree.

The steering committee worked hard to assure the more moderate supervisors that the amendments would meet the needs of the constituents pushing for the original legislation. At the same time, they had to go back to their own base repeatedly to make the case that the new added tenant protections would help limit evictions. While eventually all partners agreed to support the compromise, anxiety persisted about whether the 10-year minimum and lifetime lease requirements would adequately protect against possible heightened market activity from real estate agents chomping at the bit to take advantage of the new ability to convert. There were also repeated discussions about whether to change course and revert back to a strategy to “kill” the legislation altogether, but political analysis consistently led to the conclusion that this was simply too risky. If we didn’t try to make it our own, it could be passed in its worst form and devastating to tenants.

From day one, the new version of the bypass proposal was framed as a “compromise” by the tenants to build public perception that pushing conversions through more rapidly was a huge concession for tenants so that the robust tenant protections and anti-speculation component would viewed as a more than fair trade off from the other side.

Tenant advocates performed an incredible feat of jujitsu by turning the original proposed legislation against itself. Now, the amended version will strengthen protections for renters and curb speculative practices in the real estate industry.

After six months of wrangling, negotiations, reversals and hand-wringing, the amended proposal was approved by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors by a veto-proof 8-3 vote, bringing even moderate supervisors on board and demonstrating that, with a lot of hard work, a winning center-left majority can still be put together in San Francisco. Driving home the tenant advocates’ position that the intent of the original legislation was never actually meant to help the TIC owners, but instead to help the real estate lobby’s lucrative condo market, the two original sponsoring supervisors actually voted against the amended proposal, even though it did what they claimed to have to have wanted to do.

A New Wave

The passion and mobilization of housing advocates seen in this fight bodes well for a reinvigorated housing movement. The issue has the potential to spark a new renters’ revolt with motivated organization, strategy, and tenants at the center of the fight. With skyrocketing rents and ever-increasing evictions, this legislation has reignited a new wave of progressive tenant mobilization, like that seen in 1979 and again in 2000 at the height of the first dot-com boom. There’s increasing talk of new ballot initiatives to define the housing justice movement for the next decade.

Activists looking to the 2014 election season are sketching the rough outlines of a tenant platform, including requiring registration of “buyouts” under threat of Ellis evictions, which speculators use to clear out buildings; a parcel tax on buildings left vacant by landlords; a law giving existing tenants a right of first refusal; a six-month exclusive negotiating period when a building is put up for sale (similar to Washington D.C.’s TOPA law); and a steeply graduated tax on rental income to put a disincentive on rent increases after an eviction or buyout. Talk of a San Francisco Tenants Convention is in the air. It’s time to get organizing!

Comments