The United States is incarceration happy. Our incarceration rate is five times as high as comparable countries, and has been the highest in the world since 2002.

This means a lot of people are being released from prison every day back into our communities, many with felony convictions. Among the challenges of reentry is discrimination in housing. A felony conviction for any member of your household, or a parent of a child in the household even if they are not going to be living there, can bar you from public housing or Section 8. Housing authorities have significant leeway in whether they actually deny people on this basis, but Human Rights Watch, in a 2004 report, found that exclusion was being practiced with zeal.

Even outside of public housing, screening tenants is considered a proper part of any landlord’s duties—be it a nonprofit or private landlord. In our own survey about how you respond to people who assume Section 8 tenants bring crime, 30% of respondents said they say “Well, not if you screen properly” and others spoke up in the comments to say that “landlords not properly screening their tenants is what brings crime.”

No one wants a problem tenant. But everyone needs to live somewhere. And if a past felony conviction is an automatic dealbreaker for all “responsible landlords,” then those returning to the community can find themselves on the streets, dependent on friends/family, or concentrated in housing in poor condition in neighborhoods with landlords who don’t care. This hardly seems like an answer that will either lower recidivism or create healthy communities.

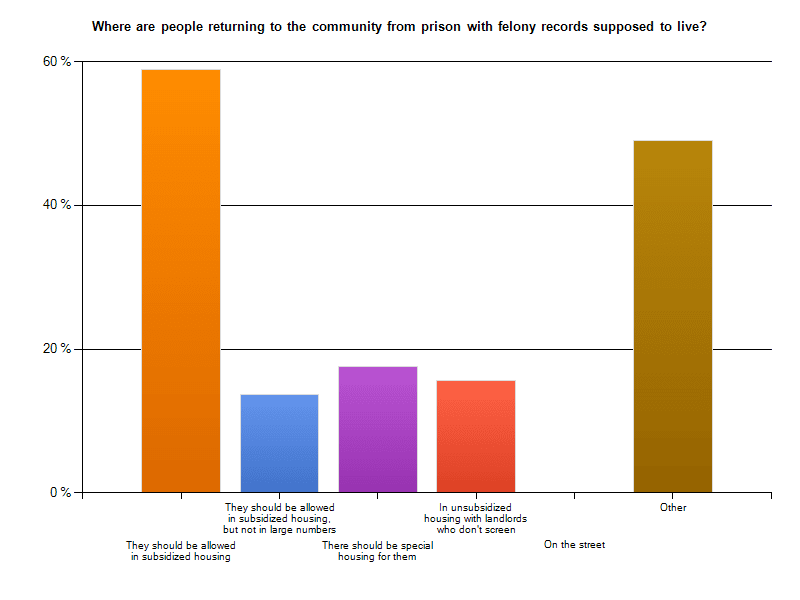

In this week’s Shelterforce poll, we asked you where you though those with felony convictions should live. It was one of our most popular surveys. A strong majority of those answering argued that people with a felony in their past should be welcome in subsidized housing, and a large number of those who chose “other” basically agreed.

(Answers as of 2/20/13.)

And here are some of things you had to say about how it does work and should work:

“As a caseworker working with several individuals in reentry, many I have served are forced to live on the streets, falling victim to new encounters with the criminal justice system. It is an extreme disgrace to see- they have paid their debt. Unless they are level 3 sex offenders and are a danger to others… they should do away with discriminatory screening practices!”

“It depends on the felony conviction. It’s not a good idea to have a felony sex offender in subsidized family housing; the offender probably has restrictions on where they can live, and the potential liability is significant, not to mention the potential harm to other residents. However, someone with a felony conviction for vehicular manslaughter doesn’t necessarily pose the same potential for safety concerns and may be a perfectly fine resident.” —Leslie, 15 years in affordable housing management, Seattle WA

“With people who own or rent private housing who they can share that housing with.”

“I understand people may not like this answer but they have paid their debt to society, if they get nothing but shut doors when they are released you end up with one of two things, people that give up on themselves or people that give up on society. Either way, having hopeless people in our communities, leads to hopeless acts. If they can’t get resources when they get back why wouldn’t they reoffend? Is the message to anyone that offended – go away you’re trash?”

“We need to begin addressing this problem on the front end – investing in neighborhoods, programs, and people instead of investing in the prison industrial complex. Our success measures would drive our strategies: falling unemployment, increased educational attainment, a significant decrease in the population in prison, and fewer returning from prison as well.” —David Ferris

“A conviction should not be the single screening factor. Consideration should be given to the type of crime (violent versus non-violent), length of time since conviction, etc. The criminal justice system should also provide better post-release supervision.”

“Ex-offenders who have gone through programs (in prison or out) that demonstrably reduce recidivism should qualify for public and subsidized housing. And there should be many more such programs offered at every stage of the trial/ conviction/ imprisonment/ release process.” —Julia Curry, housing nonprofit employee

“People who have been in prison have paid their dues to society, and therefore should be allowed to live where they want to and can afford to live.” —Wendy McNeil

“They should be able to live where they want to live depending on their convictions. Someone with a drug offense or minor conviction of some sort poses less of a threat to a community than someone who was a sexual offender or someone who was violent. Yet even these people, if you can demonstrate that they have truly been reformed, should also be able to live where they want. The problem with our prison system is that it is not as much as about reform and helping those who got in trouble turn their life around as it is about punishment.”

“They should be allowed in subsidized housing with a sponsor and a job. The sponsor should not be a case worker or parole officer but someone who lives with them. After five or so years with no further convictions -they should be allowed in SH without a sponsor.” —Stacey Tice

“Create a housing support system that allows the fomer offender and their family to move in together. That housing support system could involve helping the family find housing away from their previous residence. The support system would include financial, educational, and physical assistance – to help the family pay security deposits, utility turn on fees or assist with rent, provide financial counselling to the family to help them budget and help with moving the family into the residence. The former offender should be able to main stream back into society with their families. If they are truly looking to escape their past, a housing support system could help the family move into neighborhoods with supportive services and where the former offender can become productive. But NOT congregant housing where everyone and their family is a former offender. That just segregates the former offenders from everyone else.”

“They should be allowed in subsidized housing with supportive services (in addition to and in collaboration with parole staff) that aid re-entry and reduce recidivism.”

—Johanna Stanberry, Project Renewal

“We should raise the bar for felonies and offer more rehabilitative services/alternatives to prison that allow people to clear their records.”

“I definitely think that the ban on subsidized housing for convicted felons is overreaching. A more narrowly tailored rule – such as reviewing felony applicants on a case-by-case basis or a rule against only violent convictions – would make more sense. In our part of the world (North Carolina) the wait is so long for Section 8 and public housing that nobody is getting in, regardless of their circumstances. At the end of the day the entire system needs to be updated to be more efficient, fair, and accessible to all members of our society.” —Shoshannah Sayers

“They should be fully integrated into ‘normal’ society. I believe that these people ‘need’ a good influence in their lives.” —Mitch

“They should be allowed in all forms of housing. However, not necessarily in large numbers or forced into neighborhoods of cities and towns which already have significant challenges.”

“They should be treated as a special needs population and all efforts should be made to connect them to housing that provides in-house support services such as emotional and financial counseling, job training and placement, and legal services. Many may choose to avoid this, seeing it as an extension of the prison panopticon, but those who embrace the opportunity would have much to gain.” —Martin

For a story about one program that’s creating a different approach to this question, see “There’s No Place Like Homecoming.” See also “Housing Authority Eliminates Ban on Ex-Offenders.”

(Photo CC BY-ND, Flickr user x1klima.)

I am a felon and am trying to find a place to live and can’t. I have not been in any trouble in five years and have a nine month old daughter. The difference between probably half of this world is that I got caught and the other half just was lucky and didn’t. But yet I can’t find a roof to be put over my head, I have a job and was not a violent offender was just young so what would ones advice be to me and my daughter

My heart goes out to you. I live in houston, tx and I have some family member and friends who are ex felons. They so or should have apt locators to service you. That help withvlocating properties. Also sometimes finding independent landlords and being honest they still have comes out there who will help

I know a man that is 74 years old is felon. It happen 20 years ago. He can’t find a place to live no one will rent to him. He needs a place to live where can he go. His name is Robert Lee Marler.