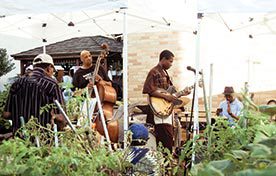

A Jazz in the Garden session at Clayton Williams Community Garden in Harlem. Photo by Jeffrey Yuen

The fortunes of many community gardens follow a boom and bust cycle, sprouting up from debris-filled abandoned lots in times of economic distress only to eventually wither away under the pressure of rising land prices. While the urban agriculture movement has gained much momentum in recent years, it needs coherent, long-term strategies to insulate urban agricultural land against the speculative forces of the market. At stake is more than mere horticulture, but food security, public health, and essential community gathering spaces.

Warning from New York City

The continuing land insecurity of many community gardens in the United States was illustrated all too well by the 1999 showdown between former mayor Rudy Giuliani and New York City community gardeners over the future of urban growing on city-owned land. Giuliani proposed to auction off 114 of the nearly 850 community gardens across New York City as the first phase of a larger disposition strategy to build low-income and market-rate housing on former city-owned land. The proposal effectively pitted affordable housing proponents against community garden advocates in a zero-sum contest. According to one representative of New York City’s Housing and Preservation Department — the organization charged with developing city-owned land — “Gardens are great, but not at the expense of new housing.” The community gardens were a feel-good story of neighborhood improvement through self-help and sweat equity, but were not viewed as a legitimate long-term land use. Giuliani made his famous pronouncement “Welcome to the era after communism,” in response to widespread protests over the proposed auction of these community-managed spaces.

In the end, two nonprofits — the Trust for Public Land and the New York Restoration Project — stepped in to broker an 11th-hour deal to avoid displacement of all 114 gardens. Over 400 other community garden sites were transferred to the GreenThumb program under the City’s Parks and Recreation Department. However, 67 gardens were eventually destroyed during the Giuliani administration, serving as a bitter reminder that government ownership of land does not necessarily ensure permanent protection.

Community Gardens as Third Places

Research has linked community gardens to diverse benefits including improved nutrition, public health, educational opportunities, increased property values and brownfield remediation. But community gardens can also play the vital social role of “third places” in neighborhood settings. In his classic 1989 study The Great Good Place, sociologist Ray Oldenberg defines the third place as any public location that hosts regular, voluntary, informal, and happily anticipated gatherings of people. While the majority of our time is spent in the first place of the home and the second place of work, it is the underappreciated third place that serves as the core setting for informal public life. The third places of lower income neighborhoods do not always get a lot of press, but serve important community functions such as establishing a sense of place, fostering broad and inclusive social interactions, and supporting civic engagement. They can take a variety of forms, such as bars, religious institutions, community centers, barbershops, and even simple building stoops. But few of these informal hangouts can activate a space and create an engaged constituency quite like the community garden. There is something unique about a garden that crosses every conceivable barrier of race, class, and religion.

“Food has always been a center of family, friends, and celebration,” says Essence, the president of Clayton Williams Community Garden (CWCG) in the West Harlem neighborhood of New York City. CWCG is one of the 114 gardens that was slated for auction and eviction in May 1999 but was instead purchased by the Trust for Public Land and eventually transferred to the newly created Manhattan Land Trust.

The CWCG is a classic example of a community garden serving as a third place, an informal public meeting place for gardeners, neighbors, and the wider public. “There’s not a lot of places here for people to gather outside of buildings and have a good time in a contained space,” says George B., long-time Harlem resident and gardener. Harlem, like many lower-income communities, suffers from lower rates of parks and green infrastructure than other neighborhoods with similar population densities. According to a 2009 study by New Yorkers for Parks, Harlem ranks in the bottom half of New York neighborhoods in terms of parkland and playgrounds per capita. Further, some residents have been reluctant to use local parkland due to lingering concerns over the quality and safety of such spaces. “A lot of people hang around outside, but it’s not always organized, and unfortunately, it sometimes disrupts life,” notes George. “We need spaces in a large city, spaces where people can gather together socially and with civility.”

There is also a strong collective memory of the CWCG serving as a green respite in this once devastated neighborhood. “A lot of the people come by on a day-to-day basis,” says Essence, “just because they have grown up with the garden being here, and they have grown up with Miss Loretta [one of the founding gardeners] being here, and they’ve seen the garden grow from nothing into something.”

The garden is particularly successful as a third space for elderly residents to congregate and maintain social contacts. “It’s good for the community and it’s good for your dignity,” adds George, a retired superintendent. “The older folks can come in and relax. Instead of sitting in their house all day, they come and sit down under the gazebo and talk about what’s going on in the neighborhood.” This third space function is particularly crucial in an area with relatively few options for seniors to commune, and where many neighborhood churches have scaled back senior citizen programming due to revenue shortfalls.

The social impact of community gardens as third spaces extends beyond their physical boundaries. The process of developing a community garden — everything from neighborhood discussions about the location and identity of the garden to tackling land use and zoning codes with planning agencies and local politicians — can serve as a community organizing catalyst. “If you can pull off a community garden, you can pull off a lot of things,” says Ben Helphand, executive director of NeighborSpace, an open space land trust in Chicago, Illinois. Prospective gardeners must learn to connect with a wide range of stakeholders, opening up new lines of communication and opportunities for civic engagement. When it comes to community gardens, it is the community that comes first, Helphand explains. “The gardening is just a wonderful, beautiful, delicious excuse for the community to come together, explore its own becoming, and put its ideas into practice, but in a more immediate way than can typically be done in modern cities.” NeighborSpace encourages gardeners to locally organize, says Helphand, and “within a basic set of rules, each garden can define its own self-determination. It’s democracy writ large.”

Given the vital social roles community gardens play, we need robust, long-term strategies to protect and support them.

Long-Term Land Security

Land security — having the right to access and use a piece of land year after year — is often considered the greatest challenge facing community gardeners. According to a 1998 American Community Gardening Association survey of over 6,000 sites, 99.9 percent of gardens viewed site permanency as an issue. High-profile conflicts have not been limited to those in New York; there was also the heartwrenching 2006 eviction of the South Central Farm in Los Angeles. Despite their current popularity, hundreds of community gardens still get displaced every year, and these integral neighborhood institutions are not easily replaced.

“You can’t just pick up a garden and drop it somewhere else,” explains Sharon DiLorenzo, a project manager at Capital District Community Gardens, a nonprofit organization in Troy, New York, responsible for creating and preserving dozens of community gardens throughout New York’s Capital Region. “Often you’re starting [a garden site] with almost no soil, so you have to bring in thousands of dollars of soil amendments, compost, fencing — that’s a huge investment. You put in all that effort and in two years or five years, someone comes along and says, ‘Sorry but we’re taking this land back.’ It’s a big investment to lose, and people get very invested in these sites.”

This issue has an additional dimension in Rust Belt cities with shrinking populations, such as Detroit, Cleveland, and Milwaukee, where the widespread availability of land has enabled a flourishing community gardens movement, but without a commensurate focus on secure tenure arrangements. In failing to develop long-term tenure strategies, these community gardens are dependent on a perpetual supply of cheap and plentiful land, which can only happen in the context of a permanently depressed local economy.

When these communities eventually rebound, development pressures will push land prices upwards, and land insecure community gardens will be at risk of displacement. By securing land today, community organizations can purchase land at favorable pricing, protect the long-term security of community gardens, and send a positive message that reinforces their belief in a bright future for their community.

At the same time, there is nothing inherently wrong with short-term community garden initiatives, as long as the land security is well matched to the program goals. For example, gardens can serve an interim use on sites that are being land banked for future development. Trouble occurs when community gardens (and gardeners) expect to be around for a long time, but don’t have tenure arrangements that allow that.

The roots of community garden land insecurity can be found in this simple fact: the unrestricted market value of urban land, which reflects conventional notions of “highest and best use,” is almost always far more expensive than income from agricultural use can support over time. However, our notions of the “highest and best” use of land rarely reflect the full range of community benefits which can be embedded in these spaces. If we are to protect community gardens from the speculative forces of the market, we will need to adopt more sustainable models of secure land tenure for community gardens. One of the most promising approaches is the land trust model.

Land Trusts

A land trust is a legally recognized, mission-driven, nonprofit organization that sustains access to land by holding property rights and providing long-term stewardship support. Land trusts protect land by either purchasing it outright, restricting use through attachment of conservation easements, or negotiating long-term leases and management agreements with other landowners. They are also guided by a democratic board structure, where gardeners and other local stakeholders have a voice in the governance of the organization.

NeighborSpace is a Chicago-based land trust that supports urban growers by holding title or long-term leases to land and providing stewardship to 81 community gardens throughout the city. This support eases the burden of site acquisition, ownership, and liability insurance, while devolving day-to-day management responsibilities to local garden groups. The land trust was established in 1996 as a result of a city-led planning process on the future of neighborhood-based green spaces in Chicago, and is supported by a 20-year intergovernmental agreement between the City of Chicago, the Chicago Parks District, and the Forest Preserve District of Cook County. “Chicago was making the claim when they established NeighborSpace that community-established and -maintained gardens are a permanent part of Chicago open space, different from but alongside the parks and forest district,” says Helphand. “Historically, gardens were thought of as temporary uses, but when it comes to land trusts, nothing is temporary.”

In Athens, Georgia, the Athens Land Trust (ALT) has developed 31 community and school gardens since 2009. The ALT is a dual-mission land trust dedicated to preserving natural areas and creating affordable housing, a model that stands in stark contrast to the divisive “housing versus gardens” framing of the Giuliani-era New York City conflict. “You can touch so many more people — and do it quickly — through community gardens than through housing,” says Heather Benham, director of operations at the ALT. ALT’s community gardens work supports its affordable housing work because it strengthens the group’s outreach to diverse local communities and positions ALT as a trusted neighborhood resource.

Such was their experience when a new pastor arrived at Hill Chapel Baptist Church in Athens. The new pastor was very concerned about health issues affecting the African-American community — hypertension, diabetes, obesity — and interested in advocacy for more nutritious food opportunities and a healthier food culture. The ALT worked with the church to design a community garden, test and till the soil, provide plants, organize volunteer workdays, and teach gardening workshops. In developing the garden, the ALT strengthened ties with the church community and its African-American membership. “They call us now if they have issues, and see us as more of a community resource than they did before,” says Benham.

Unlike many land trusts, the ALT does not address long-term land security through outright ownership or conservation easements. Georgia property tax policies make it prohibitively expensive for the ALT to hold title to urban garden land, because it is uniformly assessed at unrestricted market value, so the organization has taken on the role of garden supporter and advocate. An actively gardened site with an engaged constituency backstopped by the watchful presence of a community-based organization can provide at least a degree of political protection.

The Best Time Is Now

We are in the middle of a unique window of time, when land values in many cities are at their lowest values in decades, while interest in urban agriculture is at historically high levels. For many community gardens, the idea of owning their own garden has until now seemed like a fantasy, but this is the time to buy and protect land — there will be no better opportunity moving forward.

The key is identifying acquisition funding. Now is the time to create a national pool of funds to acquire and permanently protect land for community gardens and other forms of urban agriculture. Similar strategies have been successfully employed for decades for rural land conservation by organizations like the Trust for Public Land and the Nature Conservancy. The philanthropic community is very interested in the issue of food security, and could very well support a well-conceived proposal for a national urban agriculture land protection initiative. Let’s work together to make this happen.

Comments