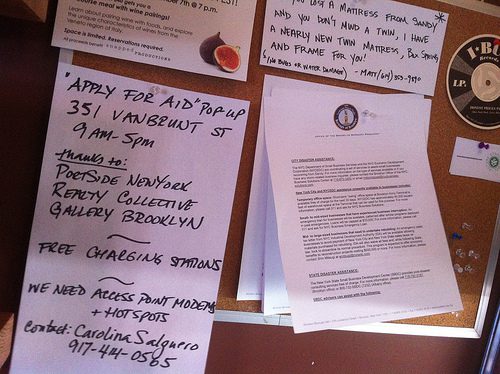

List of needs at an aid station in Red Hook, Brooklyn. Photo by Flickr user Shelley Bernstein, CC BY-NC

The terrible impacts of Superstorm Sandy and its aftermath demonstrate the need for more robust disaster planning, not to mention a reconsideration to some extent of various waterfront redevelopment schemes in storm zones.

Besides the terrible reality that many people died, some because they ignored evacuation warnings—and how many times have we ignored such warnings ourselves having been lulled so many times by “sky is falling” warnings that never came to pass, especially by seemingly hysterical weathercasters on television news programs?—we see that many cities and states lack the resources to step in and replace lost housing when public housing, homeless shelters, hospitals, and nursing homes are damaged as a result of storms and other disasters.

According to the New York Daily News many public housing complexes in New York City were damaged by Superstorm Sandy, tenants were left with very few alternative housing options, and the agency hasn’t appeared to be very empathetic to their plight. [Ed. Note: In fact, NYCHA residents are still being charged full rent for units with no heat or services. And they are not happy about it.]

The New York Times reported that, five days after the storm, almost 10 percent of the 2,600 buildings operated by the New York City Housing Authority were without power or other critical services. Most of these buildings were located in low-lying areas and/or near water, with boilers most often located in basements and susceptible to flooding.

Cities where a large number of people are housed in multiunit residential buildings have limited alternatives if those buildings go out of service. Temporary trailers from FEMA work fine for single family housing dwellers but don’t scale well for the number of tenants typically housed in apartment buildings. (See Superstorm Sandy leaves many homeless.)

The GAO report DISASTER ASSISTANCE: Better Planning Needed for Housing Victims of Catastrophic Disasters indicates that federal disaster planning for housing provision and public housing after disasters doesn’t address multiunit housing to the degree that it is necessary.

To better prepare, especially as storms become more violent and damaging, even if not necessarily more frequent, public housing organizations are going to have to update their disaster planning activities and build more resiliency into their organizations. For example, the disaster plan for Alabama’s Boaz Housing Authority addresses extreme heat, flooding, tornadoes, and winter weather.

Some lessons from Superstorm Sandy:

-

- Disaster planning for public housing systems individually and at the state and federal levels must be updated (e.g., HUD’s Disaster Recovery Toolkit doesn’t seem to address how to provide housing if multiunit buildings have been lost).

- Update disaster planning for individual properties as part of asset and risk management programs as well.

- Build resiliency into at-risk properties by moving critical systems (such as boilers) out of danger zones.

- Build backup and redundancy into at-risk properties.

- Identify opportunities for re-housing and supporting tenants as necessary (military theater type housing and supports could perhaps be an option, held by HUD and FEMA in reserve).

- Make plans to provide special assistance to seniors, the disabled, and the infirm (See Disabled people especially vulnerable in calamities such as Sandy, Identifying Vulnerable Older Adults and Legal Options for Increasing Their Protection During All-Hazards Emergencies: A Cross-Sector Guide for States and Communities.)

- Engage residents in disaster planning beforehand.

- Upgrade security plan and methods of communicating outward to residents, especially when traditional methods are at the mercy of electricity.

Finding the money to do this will likely be difficult, and disaster preparedness is yet one more item that needs to be added to a long advocacy agenda for public/social housing stakeholders. But given the attention to the issue in the wake of Superstorm Sandy, agencies and organizations should push forward, while people are concerned and aware.

Comments