At El Mercado, there was a clear real-estate development aspect to the project with capital to be raised and spent in rehabbing it and a budget to be met to operate it. Bickerdike also placed a priority on creating a local benefit.

As initially envisioned, El Mercado would be a success only if it met several broad goals:

- Area residents were the overwhelming majority of beneficiaries of economic opportunities within the project, including both micro-businesses and jobs.

- Neighbors benefited from the availability of ethnically oriented fresh and prepared foods (which was hard to get in the community).

- The community achieved a sense of pride in its accomplishment, in the ability of a community-controlled project to do well and stand as a model, and from that sense came a renewed confidence in and commitment to the area.

El Mercado Public Marketplace was a great idea and represented an incredible creative and development effort. Nevertheless, as originally structured, it failed to achieve all three goals.

During El Mercado’s predevelopment phase, Bickerdike did very little market research beyond obtaining data on supermarket gross sales and an estimate of the sales volume for the site’s prior occupant. Based on those figures, Bickerdike estimated sales projections for the stalls that, if achieved, could easily have supported 30-40 successful small businesses. Staff conducted extensive community outreach, which provided ample anecdotal evidence of community interest and support, but did not more formally assess the interest and capability of area entrepreneurs.

El Mercado was funded through a mix of federal grants and equity Bickerdike had raised from successful multi-family housing developments. Had those resources not been available, Bickerdike would have had to seek private bank financing and the project would have been subjected to a more rigorous underwriting process. Potential lenders would have asked for evidence of community interest in the project — to validate expectations of sales and marketability of the booths. Ironically, Bickerdike’s ability to finance the project without debt let the organization get away without having to prove those expectations reasonable to anyone.

In order to enable start-ups to open booths in El Mercado, Bickerdike provided significant financial and technical assistance. It partnered with the Women’s Self-employment Project (WSEP), a group well respected for its support of start-ups by women. WSEP provided direct technical assistance to the businesses and helped administer a start-up loan fund. Because almost none of the potential vendors were bankable, Bickerdike capitalized the loan fund itself.

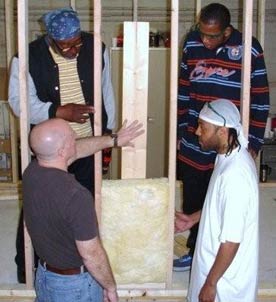

Bickerdike also helped each business build its stall. El Mercado was designed as an open market, with 48”-high partitions delineating the 37 booths. Each booth had its own utilities, and there were walk-in coolers for the fresh-food stalls. Beyond that, vendors had to supply counters, display cases or coolers, and workspace. Working with Bickerdike, and with some help from Humboldt Construction, vendors built out their booths, in many cases using plywood counters and displays made on site.

El Mercado had a rousing opening week, complete with a full front-page color picture and story in the Chicago Sun-Times, the city’s tabloid daily, and crowds in the hundreds for four straight days of opening celebrations and entertainment. After that, sales were miniscule and flat.

The community clearly knew about the project, and there was no trouble attracting hundreds of people to El Mercado for entertainment or cultural events. And shoppers came but ultimately they spent very little money. Some came for a jibarito sandwich for lunch or a tropical shake, enjoyed the sunlit atmosphere, and left without doing any shopping for fresh food. The small branch of a local bank with which Bickerdike had done business for years selling dairy and other goods subsidized through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children did well and attracted customer traffic.

Still, several of the small businesses failed, each one leaving Bickerdike with unpaid loans and rent and El Mercado with yet another gaping hole. Bickerdike took over a few of the booths and ultimately did a restructuring to bring in a local mid-sized business to operate a dry-goods business occupying about 40 percent of the space. The grocer paid rent to Bickerdike regularly, unlike many of the smaller businesses, and sales picked up a little. Still, the project was losing money every month for Bickerdike, and the group knew it could not sustain those losses indefinitely.

El Mercado first opened in November 1992. By the time I left Bickerdike in February 1995, it was clear that something drastic had to be done with this failing project — it was no longer reasonable to continue the same strategies, hoping that eventually customers and small businesses would materialize and the project would become viable.

In October 1995, under the direction of its new executive director, Joy Aruguette, Bickerdike restructured the project. Proposing to eventually abandon the concept of having many booths operated by independent small businesses. Instead, the building would be leased to a mid-sized grocer, who would pay Bickerdike rent under a net lease. This adaptation — avoiding a long-term failure and producing a successful project — was possible for a number of reasons. The sponsor and its federal grant agency were both willing to pursue the modification. The underlying economics of the real-estate project were sound, even if the public market use was not. And the CDC itself was strong enough to sustain the project through the lean years without being forced to abandon it.

Comments