Emily Taylor started as the associate director of resident services for Champlain Housing Trust in Vermont four years ago, shortly after the pandemic began. With 2,500 affordable apartment units across the nonprofit housing agency’s portfolio, Taylor helps manage a team of resident service coordinators who provide direct services to tenants who are falling behind on rent. This includes connecting tenants with local support services, social service programs, and/or federal programs that could provide some financial relief.

Since Taylor began, the need for support has become so high that she and her director are now going out themselves, meeting directly with residents who are forced to choose between rent and other pressing expenses.

“Last year alone we provided services to 850 residents,” she says. “We’re nearing a point where we’re providing one-on-one direct services to almost half of all residents who rent from us.”

In four years, the amount of unpaid rent at Champlain Housing Trust properties has tripled—from $250,000 in rental arrears pre-COVID to $750,000 today, according to Michael Monte, the organization’s chief executive officer.

This is a dilemma familiar to nonprofit affordable housing organizations across the United States. Four years after COVID-19 first wrought havoc on the American economy, nonprofit housers are dealing with a tremendous amount of rental arrears.

Meanwhile, many federal and state assistance programs that provided a vital lifeline to these housing organizations and their tenants during the pandemic have dried up. That loss, coupled with inflation and ballooning operational expenses—including skyrocketing property and liability insurance premiums—has caused many organizations to feel hamstrung in their ability to provide services and maintain their properties.

Altogether, it has created a difficult operational reality for nonprofit housers.

“It has the potential to become overwhelming,” says Andrea Ponsor, CEO and president of Stewards of Affordable Housing for the Future, a collaborative of nonprofits that operate affordable housing developments in 49 states. “It’s a very simple equation to maintain a stable property in some ways—it’s revenue minus expenses. And that’s not what’s happening right now.”

A recent survey by the collaborative, with data from nine of its member operators representing 100,000 units, showed a $44 million increase in unpaid-rent receivables over a five-year period—a 336 percent increase, Ponsor says. At the same time, operating costs in their combined portfolio have gone up 36 percent.

In Los Angeles, Abode Communities has $4.4 million of unpaid rent on the books; Community Roots Housing in Seattle has $3.3 million. And that’s not taking into account the millions in federal and state aid they received in the years following the pandemic to offset rent arrears. Factoring out relief funds, Holly Benson, the CEO and president of Abode Communities, says the true figure is $8 million. And Chris Persons, Community Roots Housing’s CEO, says total rent arrears since the pandemic are closer to $9 million.

“What we’re seeing is that the rate of nonpayment is not as bad as it was in 2020 and 2021,” says Persons. “But it seems to be stuck at a certain level.”

The trend is very concerning, not only for ownership and property management, but also at the macro level—community, residents, investors, and lenders.”

Carlos Gonzalez, The NHP Foundation

Carlos Gonzalez, senior vice president of asset management at The NHP Foundation, a nonprofit multifamily housing provider in Washington, D.C., says his company is experiencing rental arrearages at dollar amounts they’ve never seen before. “Our balances are simply off the charts,” Gonzalez says.

“We haven’t seen any improvement on collections since the pandemic hit, regardless of rent assistance programs and our collective efforts to keep our residents in their homes,” Gonzales says. “The trend is very concerning, not only for ownership and property management, but also at the macro level—community, residents, investors, and lenders.”

Beacon Communities—a real estate firm that manages 19,000 affordable and market-rate units, the bulk of which are in Massachusetts—is in a similar situation. In an emailed response, Beacon wrote that “in many cases, residents have been very responsive, and we have succeeded in implementing internal repayment plans. However, coming out of the pandemic, delinquency rates increased across the portfolio industry-wide, and it has been challenging to convince a significant number of residents that they need to pay a portion of their rent consistently.”

Faced with this reality, agencies are being forced to balance their community-driven mission with operational and financial realities to keep their properties up and running. It often means deferring maintenance, decreasing resident services, or having a little less on-site staff to help people have a quality place to live, Ponsor says.

“When you have a healthy portfolio, you can elevate your social mission and make sure that people are housed,” says Robin Hughes, the president and CEO with the Housing Partnership Network, a collaborative of more than 100 housing and community development organizations across the U.S. “But when half of your portfolio is in trouble, it’s more difficult to implement the sorts of social policies that you’d like to.”

‘It Does Feel Truly Unprecedented’

Rent arrears in all sectors remain at “crisis levels,” according to data from the National Equity Atlas. Nearly 5 million households are behind on rent, according to the organization, which estimates there is more than $9 billion in total rent debt.

But data specific to nonprofit affordable housing is hard to find.

Hughes says members have data about their individual properties, but the network has yet to create a centralized data source, “to really understand the magnitude that rent arrears is happening, the rate at which it’s happening, and then the impact that it’s having on portfolios.”

“We hope to get there,” she says. “Where we need to collect data is where this is happening, what parts of the country and what submarkets it’s happening [in].”

And, Hughes adds, which “local state policies have either prolonged the eviction moratorium or have in place policies that make it more challenging to address these issues.”

[RELATED ARTICLE: During the Pandemic, Community Development Organizations Prioritize Relief and Assistance Work]

Rent arrears exploded after the pandemic began, when thousands were left without work and without income. Federal stimulus programs helped some nonprofit agencies keep their books balanced and tenants’ rent caught up.

But federal stimulus money often wasn’t enough, and eviction moratoriums ensured that tenants who couldn’t pay their rent could keep their housing.

At the Housing Partnership Network, Hughes says, they are finding that higher rent arrears often correspond to what the eviction process looks like in a given state or locality, and how long the courts take to process evictions.

“So, in places like Washington, D.C., for example, it could be a whole year before an eviction is processed,” she says. “That takes a higher rate of rent arrears in that space. We’ve seen that in Michigan as well.”

In areas with strong tenant protection policies, rent arrears are higher, Hughes says. While these policies are important to protect low-income residents from slipping into homelessness, Hughes says it’s critical that such policies be coupled with support for the operation.

“Having 20 percent, 30 percent of your tenants not paying has a significant impact on you being able to keep up with day-to-day maintenance and keep the property afloat,” she says.

Hughes noted these patterns are only anecdotal, and “without real data, it’s really hard to reach a conclusion.”

The pandemic hurt a lot of industries really badly, but I would make the case that it impacted the affordable housing industry more than most.”

Chris Persons, CEO of Community Roots Housing

Persons of Community Roots Housing says, “The pandemic hurt a lot of industries really badly, but I would make the case that it impacted the affordable housing industry more than most.”

Nonprofit housing agencies say they try to avoid evicting tenants. Monte with the Champlain Housing Trust says his organization does not evict for no cause, and makes sure its resident services team has exhausted every federal, state, or local program available to them to keep tenants in their housing. The cause for eviction, he says, “has to be pretty dramatic.”

“People don’t get evicted because they don’t pay rent. They usually get evicted because they don’t respond or talk to us or work with us or figure something out,” he says.

The organization has in some cases been forced to evict tenants—usually after bad behavior coupled with growing arrears that, he says, leaves them no choice.

“Every eviction is bad. . . . It’s a struggle, and it’s not good for the property, it’s not good for the tenant, and it’s not good for the community,” he says. “We try to do everything we can to avoid it.”

‘HeadwinDs’

Some organizations are seeing signs of improvement. Benson with Abode Communities says her organization has started to see a reduction in rent arrears on a monthly basis, but noted that “there are enough (tenants) that are consistently not paying.”

The Community Builders, a Boston-based nonprofit that manages over 13,600 apartments in 13 states, has also seen some month-to-month improvements—a big change from this time last year, says Bart Mitchell, the organization’s president and CEO.

“It’s not back to pre-COVID levels, but it is interesting that every month this year has been better than the previous month,” he says.

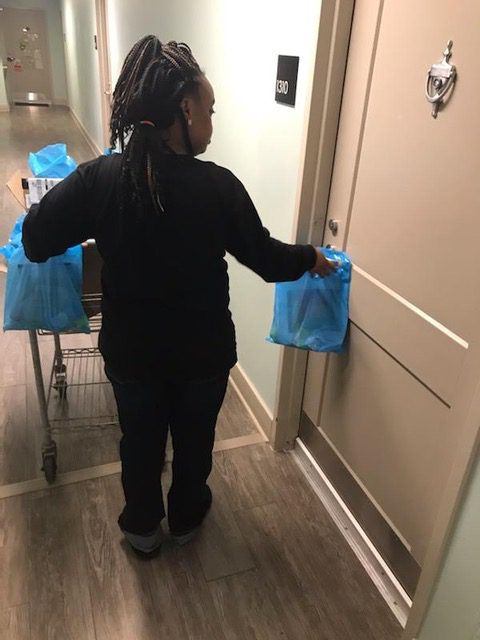

Much like the Champlain Housing Trust, teams with The Community Builders flag tenants who may be having trouble and try to intervene to find them help.

With their property management staff cooperating with their community life staff, “it means if somebody does fall behind on rent, then they may get a notice,” Mitchell says. “But often, even before that, they’ve got a call or knock on the door from our community life staff saying, ‘Hey, what’s up?'”

But delinquent rent remains high, he says. And, despite signs of improvement, “it does not relieve the fact that last year was really the year where . . . rental assistance was not available in the big amounts that it was previously.”

“That has made it hard,” he says.

Mitchell says his organization and other larger nonprofits have communicated this to policymakers.

“To the extent that we are some of your best delivery mechanisms for housing, please know that this fact pattern—with the decline in the availability of emergency rental assistance and the pressures on families—is going to hurt your best affordable housing landlords,” he says.

While there may be pockets of improvement, other budget pressures also affect nonprofit organizations. In Los Angeles, Abode Communities could in years past typically count on their property and liability insurance premium making up 10 percent of their overall property budget.

But from last year to this year, their insurance premium has increased by 347 percent, says Benson.

“And it’s not like the other line items shrunk,” she says. “Even if we didn’t have the revenue challenge, that is very, very difficult to absorb.”

Indeed, very few properties in Abode Communities’s portfolio have been able to absorb that. With hits to both their revenue and expenses, the organization has seen an increase in properties that do not quite break even. Where in years past Benson would have 4 or 5 properties that could not quite break even, now she’s seeing 14 or 15.

It’s a problem that only recently began to affect nonprofit housers already dealing with revenue side issues.

“With so many headwinds coming at our members at this point in time, it does feel truly unprecedented,” says Hughes of the Housing Partnership Network. “It’s impacting the sector in a significant way.”

In Minnesota, lawmakers have taken steps to address these headwinds. A broad housing package, signed into law in May 2023, allocated $45 million to the state’s Family Homeless Prevention and Assistance program, providing emergency rental and utility assistance to families experiencing or at risk of homelessness.

The bill also raised sales taxes in the Twin Cities metropolitan area to generate permanent revenue for housing programs. Another program, passed this legislative session, allocates $50 million to support the recapitalization of distressed affordable housing properties, among other things.

That’s important, says Ellen Sahli, president of Family Housing Fund in Minneapolis, because it’s the first time state policymakers have recognized the type of intervention that’s needed. “We hope to build on that,” she says.

‘People are Struggling’

Taylor of the Champlain Housing Trust was recently notified about a single father in one of the organization’s apartment units.

The man had had a job that kept him financially stable. But when he unexpectedly took custody of his two children, he cut back his hours to work around their school schedules. Forced to juggle the new expenses of caring for his children with his other bills, the father started to fall behind on his rent. He eventually lost his job.

Taylor and her team were able to apply for rental arrears assistance through one of Vermont’s community action agencies and secured a housing choice voucher through the local housing authority, providing some stability.

But the father’s situation, Taylor says, underscores the precarious tightrope low-income residents in nonprofit housing often must walk.

“We see a lot where people are feeling like they have to choose among their essential needs, so for some people, they don’t have enough money for food and rent, so they’re picking one or the other,” she says. “People who live on a fixed income through various state and federal benefits, it’s not enough to sustain what the cost of living is.”

Rent arrears show that while federal rental assistance funding has dried up, the need hasn’t, says Sahli of the Family Housing Fund.

“It’s not [that] the tenants don’t want to pay rent,” Sahli says. “There is not support for them to pay rent.”

Taylor says that in many ways, the reasons people fall behind are the same as they were before the pandemic.

But, she says, “The discourse about how maybe the collective ‘we’ have created a system that people rely on and not pay their rent—I think that’s interesting to look at, but more through the lens of, we are serving people on a fixed income that is not enough to cover the general cost of living.

“It sparks a larger conversation around what our system of care can really look like . . . if we want to meet an actual change of helping people maintain their housing.”

Additional reporting was contributed by Shelterforce’s Shelby R. King.

It’s been 4 years (not really) with the pandemic and the last 2 years was when people should have gone back to work or looked for a job. Many probably didn’t because they have become comfy on the gov’ts money. I know rents have gone up due to many reasons and some have began to almost like price gouging because they knew the State would help pay.

It’s time for people to get off the “gravy train” and, at the very least, help support themselves.. The State is going broke by giving away so much money to people that are capable of supporting themselves.

Employers are trying to increase their rate of pay to their employees but it hasn’t been easy on them either. Everyone needs to try.

Thank you

Affordable housers are struggling. Renters are struggling. But who is not struggling? Who continues to get paid and paid well no matter what? We need to look at the overall structure of how affordable housing projects are financed and operated. There needs to be less extraction of benefit for investors, more risk-sharing, more direct subsidy for projects, and willingness to implement creative solutions like government-backed insurance captives, and dedicated and prioritized resources for energy efficiency upgrades for affordable housing.